Anyone studying a science at university will have sat in many lectures where the slides of historical background contain seemingly endless photographs of affluent white men. The efforts of women in science are often overlooked due to unequal opportunities in the workplace, and lack of recognition of their achievements by the scientific community. Despite this, strong intelligent women have made, and continue to make, huge impacts in all areas of science. Here are some women who have revolutionised their respective fields, and current female scientists at Oxford who are following in their footsteps.

Beatrice Shilling (1909) was a British aeronautical engineer during World War II. She designed a device to prevent Spitfire engines losing power during combat manoeuvres, a mechanical shortcoming which had previously led to many casualties. Alongside this, she raced motorbikes and is one of only three women to have been awarded the British Motorcycle Racing Club Gold Star for lapping the circuit at Brooklands, Surrey at over 100mph. According to anecdote, she refused to marry her husband George Naylor until he had also earned the award. Shilling was once described by a fellow scientist as “a flaming pathfinder of Women’s Lib[eration]”; she always rejected any suggestion that as a woman she might be inferior to a man in technical and scientific fields.

Eliza Argyropoulos is a fourth-year engineer at Keble College who is currently building a novel form of drone as part of her Masters’ degree. She fell in love with physics aged eleven when her teacher described the subject as ‘the study of things as small as atoms to things as large as the universe.’ She first began to consider a career in engineering after a visit to CERN aged sixteen. She hopes to push the boundaries of possibility in her career, and has aspirations to mentor younger generations of women in science to show them that there is no limit to what they can achieve.

Dame Anne McLaren (1927) made fundamental advances in genetics and helped develop IVF. She read Zoology at Oxford and began to develop methods of IVF by growing mouse embryos in tissue culture. She became the first female officer of the Royal Society in 331 years, when she was appointed as their Foreign Secretary between 1991-1996 and travelled widely, becoming a role model for women in science. Dame Anne spent the next 15 years at the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh, where she continued researching the reproduction, growth, and genetics of mice. Her greatest achievement came in 1958, with the first successful delivery of mice that had grown as embryos outside the mother’s womb. This ground-breaking work paved the way to the world’s first test-tube baby in 1978.

Prof Frances Ashcroft is a professor at the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics at Oxford University and a fellow of the Royal Society. She began her career studying Natural Sciences at Cambridge, driven by a love for British wildlife and a curiosity about how the world works. She is now internationally recognised for her research into ion channel function in insulin secretion. Her current projects include identifying the underlying mechanisms behind type two diabetes and determining the role of the potassium channel implicated.

She is inspired by Marie Curie and Dorothy Hodgkin, who made huge contributions to science despite the judgement of others, but also takes inspiration from those close to her. Her view on equality in science is hopeful as she recognises the huge improvements she has seen during her career and the men who have supported (and championed) the push for a more equal community.

Elizabeth Anderson (1836) was the first Englishwoman to qualify as a doctor, despite being initially denied entry to medical school. She qualified in 1865 by passing the Society of Apothecaries exam, and later obtained a degree in medicine from the University of Paris; a qualification the British Medical Register refused to recognise. Despite this, Anderson went on to found the New Hospital for Women in London which was staffed entirely by women. Her determination inspired other women in the field, and in 1876 an act was passed permitting women to enter the medical professions. In 1902, Anderson retired to Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast, and in 1908 became mayor of the town, and the first female mayor in England. She was also a member of the women’s suffrage movement and her daughter Louisa was a prominent suffragette.

Helen Stark qualified as a doctor at Cambridge University and is now pursuing a doctorate in acute rejection in organ transplantation at Oxford. She hopes to develop a diagnostic test for organ rejection to help improve success rates during transplantation; something which would save thousands of lives. Helen is driven by a desire to improve outcomes for her patients in both the lab and the operating theatre and hopes to one day become a clinical lecturer to pass her knowledge onto a new generation of medics. She hopes that in future more senior research roles will be held by women as this is still an area predominantly occupied by men.

Ada Lovelace (1815) was born the only legitimate child of Lord Byron, but grew up without her father’s presence. She was taught science and mathematics, despite this being unusual for girls at the time. Aged 17, Lovelace met Charles Babbage who designed the difference engine, the first form of early computer tasked to do simple calculations. Ada went on to develop the machine by writing the first piece of code, introducing letters and symbols rather than just numbers. She broke the boundaries of thinking in the emerging area of computing and is often credited as the first computer programmer.

Miriam Stricker is a DPhil student working on applying machine learning techniques to data of the human immune system, with a focus on genetic regions that influence the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy treatments. She hopes that her work will contribute to more targeted treatment strategies and improve the lives of others, as well as our knowledge of human disease. She is grateful for advances in equality in the scientific community but recognises that prejudices still exist today. She remembers her computer science teacher telling her that he was ‘astonished’ that she was able to keep up with the boys in his class and, due to interactions like this, decided to mentor female students who are interested in studying STEM subjects.

Mary Somerville (1780) was a Scottish astronomer and science writer who became one of the first female members of the Royal Astronomical Society. Upon her death in 1872 it was declared in The Morning Post that “Whatever difficulty we might experience in the middle of the nineteenth century in choosing a king of science, there could be no question whatever as to the queen of science”. Her work includes translating Laplace’s algebra into common language and the prediction of the discovery of the planet Neptune. Somerville College in Oxford was named in her honour to ‘reflect the virtues of liberalism and academic success’ that the college wished to promote in its students. Somerville’s undeniable intelligence transformed the position of women in science and the word ‘scientist’ was actually coined due to a reviewer of her work being unable to use the standard phrase of the time ‘man of science’ to describe her.

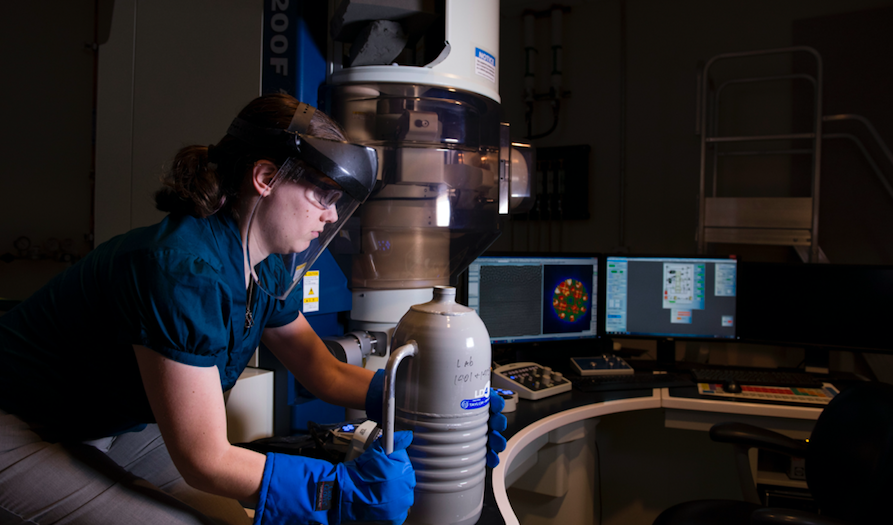

Amy Hughes is a physicist studying for her PhD at Oxford. She describes Somerville as one of the women who has inspired her most, having researched her as part of a project for the Oxford Women in Physics Society. Amy studies quantum computing, in which atoms are manipulated using laser beams to represent binary information; an area which has the potential to revolutionise computing. Amy describes having ‘grown up with science as a common topic of conversation’ and credits her initial interest with the inspiration of her father, who is a scientist, and her teachers. She continues to be inspired by those around her, solving problems as part of a diverse and supportive team.