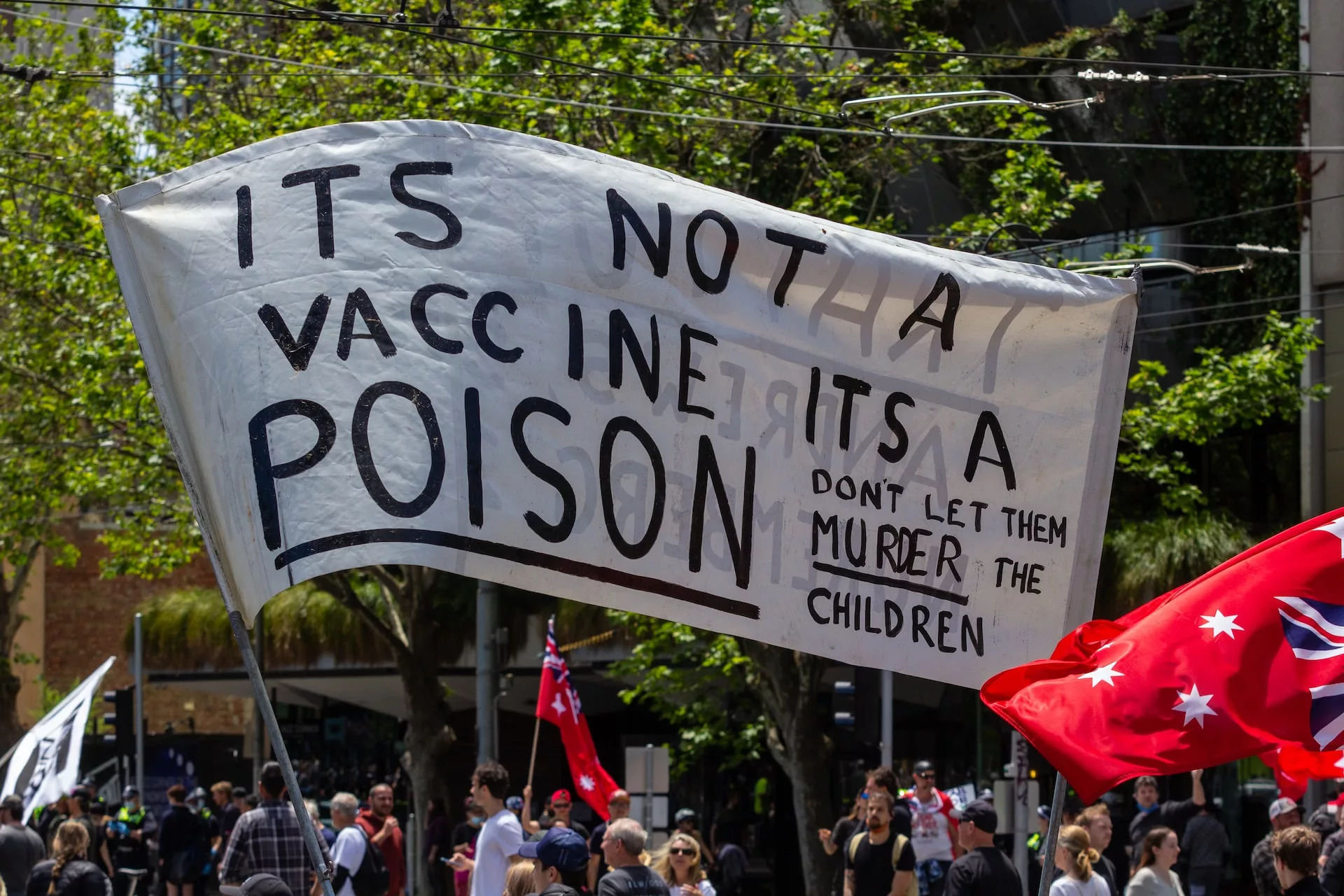

Trust in scientific research is the backbone of public health interventions, yet many are dubious about science. Photo credit: DJ Paine via Unsplash

Current issues such as COVID-19 and climate change require support by everyone in our democracies. Yet, as COVID-19 raged, millions of people refused to take vaccines because they did not trust the science behind them. Less than one in four Republicans see climate change as a major threat. In the book, Why Trust Science, Oreskes argues why we should trust science and how to restore trust in science. Oreskes is a historian of science at Harvard University. She is the author of Merchants of Doubt, the ground-breaking book on the successful efforts of oil and tobacco companies to slow scientific consensus on the harmful effects of their respective businesses. The book is in four parts: a first part by Oreskes, four chapters written by guest writers on specific issues, followed by a reply by Oreskes to the writers, and a summary.

Oreskes’ central claim convincingly argues that science achieves objectivity through its social structure. It is through the process of scientists correcting each other (through peer review) and criticising each other (through new papers) that we achieve objectivity. Furthermore, diversity, be it geographical, gender, or background, ensures that assumptions are questioned and safeguards the objectivity of science. While science may seem undecided, often as the research accumulates, a scientific consensus emerges, such as, on the causes of climate change. The objectivity of science gives us reason to trust this consensus is likely true. It is only likely true because scientists can, and have been, wrong. She analyses some examples, such as eugenics, to encourage people to judge the science for themselves, by looking at the variety of evidence, scientists’ openness to new methods, scientists’ absence of clear value biases, and humility.

Oreskes’ central claim convincingly argues that science achieves objectivity through its social structure.

Oreskes’ main argument for how to restore trust is to appeal to people’s values. She contends that scientists pretending to be value-free is not only wrong but counterproductive. Scientists hiding behind the veil of objectivity is part of what makes people wary of trusting them. Scientists need to form bonds of trust with their fellow citizens. Thus, she convincingly proposes to embrace the values involved in science. These values, such as wanting to cure diseases, helping the economy with creativity, or protecting the natural world, are widely shared. Sharing such values appeals to the public and should increase their trust in science.

Furthermore, to reach those who are sceptical, she gives the example of basing descriptions of climate change on Christian values and teachings. This allows her to reach millenarians who believe the world is about to end, by finding citations from the Bible such as, ‘But concerning that day [where the world ends] or that hour, no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father’. The problem is that currently most scientists prefer to hide behind the image of objectivity and do not want to discuss values.

Later, Oreskes then makes room for other perspectives to enlighten the debate: Lindee, Lange, Edenhofer, Kowarsh, and Krosnick. Susan Lindee makes the argument that by emphasising the science in everyday objects that work, we can restore trust in science. People trust the working of everyday objects such as frozen peas and so by emphasising the science involved, they might be induced to trust science more. Frozen peas involve ‘[modern] geological sciences in the oil and gas industry, the chemical development of plastics, scientific agriculture and the genetic modification of crops, chemical understandings of the freezing process, even the social sciences of marketing and persuasion’.

While fun, Oreskes later refutes this argument by highlighting that people compartmentalise: they trust science in general, because it suits them to eat frozen peas, and distrust science when it goes against their deeply held values. She gives the strong example of evolution: many Americans accept DNA carrying hereditary material. Yet, they do not see evolution as a process altering the DNA of populations. People object to the theory of evolution because it goes against their religious beliefs: it has the amoral consequence that humans have arisen not by divine reason, but by chance. Similarly, GW Bush famously stated at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit of 1992 on climate change, ‘The American way of life is not up for negotiation. Period’. Values usually take precedence over facts.

The next two chapters of the book seem a bit of a mishit, and less relevant to the general argument: a formal philosophy of science, and a climate policy focused chapter.

Oreskes seems to always want to protect scientists and so does not address such questions enough.

A further criticism of the book is that Oreskes does not address how we should deal with the uncertainty and value-ladenness often inherent in science. Throughout Covid, we kept hearing scientists bang on about the need for strict lockdowns as warranted by the science and what would save the most lives. This was based on models, such as the Imperial College London model predicting 500,000 deaths from Covid in the UK. Yet, discussions of the model did not mention the fact that the death estimate, on top of being very uncertain, was based on a scenario with no government intervention and no change in behaviour. In this way, when deciding on what to include in their model, scientists made incredibly value-laden judgments on their own that had an enormous influence on the policy recommended from it. Oreskes herself says that the countries that did well during Covid are the countries that ‘followed the science’. However, ‘the science’ was often fraught with ethical questions, such as how to weigh up short term gains in lives against the long-term mental health, and economic costs of lockdowns. Oreskes seems to always want to protect scientists and so does not address such questions enough.

All in all, the book is a very readable and powerfully argued defence of the scientific enterprise. I like how it really engages with why people do not trust science, and how to encourage people to trust science more. She provides an original perspective, though I feel she could add more examination of the literature on trust to see what really works. I further like how she really engages with criticisms of science. She tries to learn from the stories of the failure of science, acknowledging the need to always keep a critical mind when evaluating scientific claims, and not to keep the doors to science closed to citizen scientists.

If we are to succeed in getting the public’s support for draconian measures to fight climate change, trust in science is paramount. This book provides tools to start to fight back against misinformation.