By Sophie Beaumont

We live in a fast-paced society that bombards us with so much information on how we should live our lives, from what clothes we should buy to what we should eat. Marketing that promotes such content holds enormous power to influence our behaviour to differing degrees. Companies push individuals to satisfy short term impulses, for example easy, cheap but unhealthy fast food, which happen to make them vast and immediate profits. Unbeknown to the consumers of this huge market, though, is that this often doesn’t benefit them. In fact, scientists are now starting to question whether fast food can be considered food at all.

Food is defined as material consisting of protein, carbohydrate, and fat that the body uses to sustain growth, repair, and vital processes and to supply energy. By comparison, junk food is high in empty calories from sugar and/or fat but contains little dietary fibre, protein, minerals and other important forms of nutritional value. According to these definitions, junk food cannot be classified as ‘food’.

Processed foods as we know them today originated for soldiers in WWII; they provided a long-lasting and convenient source of high energy foods that could be easily transported, with the term ‘junk food’ first appearing in the 1950s. These foods grew in popularity, particularly in the US, as they were high in fat and sugar, hence very palatable. They also saved valuable time in the kitchen, especially with the introduction of the microwave.

Junk food is high in empty calories from sugar and/or fat but contains little dietary fibre, protein, minerals and other important forms of nutritional value. According to these definitions, junk food cannot be classified as ‘food’.

Nonetheless, these new, high-fat diets meant that obesity first became realised as a disease in 1948, with its prevalence increasing ever since. Rates of coronary heart disease also skyrocketed. A series of studies [HC1] in the 1940s found correlations between high-fat diets and high-cholesterol levels. Thus, many scientific bodies (including the American Heart Association) were in favour of a low fat diet to prevent heart disease in high-risk patients. In the 1960s, the low fat diet began to be promoted to the whole nation, not only high-risk heart patients. This approach was believed to be the solution to the increasing weight of the American population. A diet low in fats is also likely going to be low in calories, as a single gram of fat contains 9 kcal, compared to the 4 kcal in a gram of protein or carbohydrates.

This low-fat diet was promoted to the public long before any sound scientific research was published on the topic. It was assumed that the human body was simply a ‘biochemical machine’, and that consuming fewer calories than you were burning would lead to weight loss. Any failure to stick with restrictive diet was therefore blamed on the individual’s willpower. To this day, the food industry is not held accountable for pushing fast food yet simultaneously promoting low fat diets, leaving individuals feeling guilt and shame that, ironically, is too often comforted by a pint of Ben and Jerry’s…

The high rates of failure on low fat diets are not surprising because over time it changes our satiety. Consuming fewer calories (as is common on with a low-fat diet) can cause the hunger-provoking hormone ghrelin to rise, a natural response to protect you from starvation. In addition, leptin (a hormone that suppresses hunger) levels decrease, increasing hunger levels and making your brain believe you are starving. This would be an appropriate evolutionary adaptation if you genuinely were starving, but not so appropriate in modern society where we are surrounded by cheap ultra-processed foods.

Since the 1950s we have received confusing and disorientating advice on how best to fuel ourselves. By virtue of availability and highly persuasive advertising we are essentially force-fed highly processed foods, which are being made ever cheaper as well as being the easiest source of energy for many.

The introduction of the low fat diet also coincided with the advent of snacking, which is now seen as respectable thanks to commercialisation. This habit has become ingrained in our society, from morning snack times in schools to ‘nutrition breaks’ at medical conferences. Before the obesity epidemic, most cultures had 2-3 meals a day with some cultures having just breakfast and a large evening meal. Since the advent of ultra-processed foods, it has been drilled into us that we must have a big breakfast (the most important meal of the day!). We should also have multiple snacks between meals to maintain our energy levels. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that this benefits us, but means we now eat on average 5-6 times a day. Although eating more frequently is advertised as an efficient method of weight loss, this in itself is contradictory. With a low fat diet resulting in increased hunger between meals, snacks were advertised to dieters by health organisations as well as the food industry. Consequently, food industry giants make more profit, and people are less hungry on their restrictive diets.

Nonetheless, highly processed, low fat snacks are generally high in sugar to make them palatable. So, increasing their intake actually increases weight for those trying to shed pounds. To make matters worse, many of the compounds found in these highly processed foods (monosodium glutamate, sugar, salt) cause addictive traits in rodents. Although these addictive properties have yet to be proven in humans, it is inevitably harder for us to stop returning to these tasty ultra-processed foods and alter the dietary patterns to which we have become accustomed.

Even if you can keep up the willpower and self-restraint to stick to your low calorie diet, following a low fat and low energy diet will have knock-on effects for your metabolism. Your body will learn to survive on less energy and weight will be maintained on lower calories. This means over time you must reduce calories further to lose more weight. The problem is clear.

To this day, the food industry is not held accountable for pushing fast food yet simultaneously promoting low fat diets, leaving individuals feeling guilt and shame that, ironically, is too often comforted by a pint of Ben and Jerry’s…

A low calorie diet that involves regular snacking or ‘grazing’ also affects insulin resistance and has been associated with type 2 diabetes. Every time you eat, increased glucose levels in your blood stimulates insulin. Snacking throughout the day will keep insulin constantly high. This increases the likelihood of becoming resistant to insulin (as in type 2 diabetes) and resistance tricks your body into thinking you are constantly hungry. As we’ve already seen, the ‘healthy’ foods people are encouraged to snack on will generally be low fat (high sugar and carbohydrate) snacks to fit with the trend of the low fat diet. This vicious cycle of hunger and snacking on carbohydrate-rich foods exacerbates the insulin spike and tends to leave you feeling hungrier than before you ate.

Since the 1950s we have received confusing and disorientating advice on how best to fuel ourselves. By virtue of availability and highly persuasive advertising we are essentially force-fed highly processed foods, which are being made ever cheaper as well as being the easiest source of energy for many. But when considering whether they can even be considered ‘food’ we come to a standstill – the definitions simply do not align and junk food does not support growth or repair. Yet often we find ourselves returning to them, not knowing where else to turn. The odds are most definitely against us. Nonetheless, with appropriate education along with management of advertising, I believe we will be able to promote minimally processed foods and enforce stricter regulations on food giants.

This article is based on:

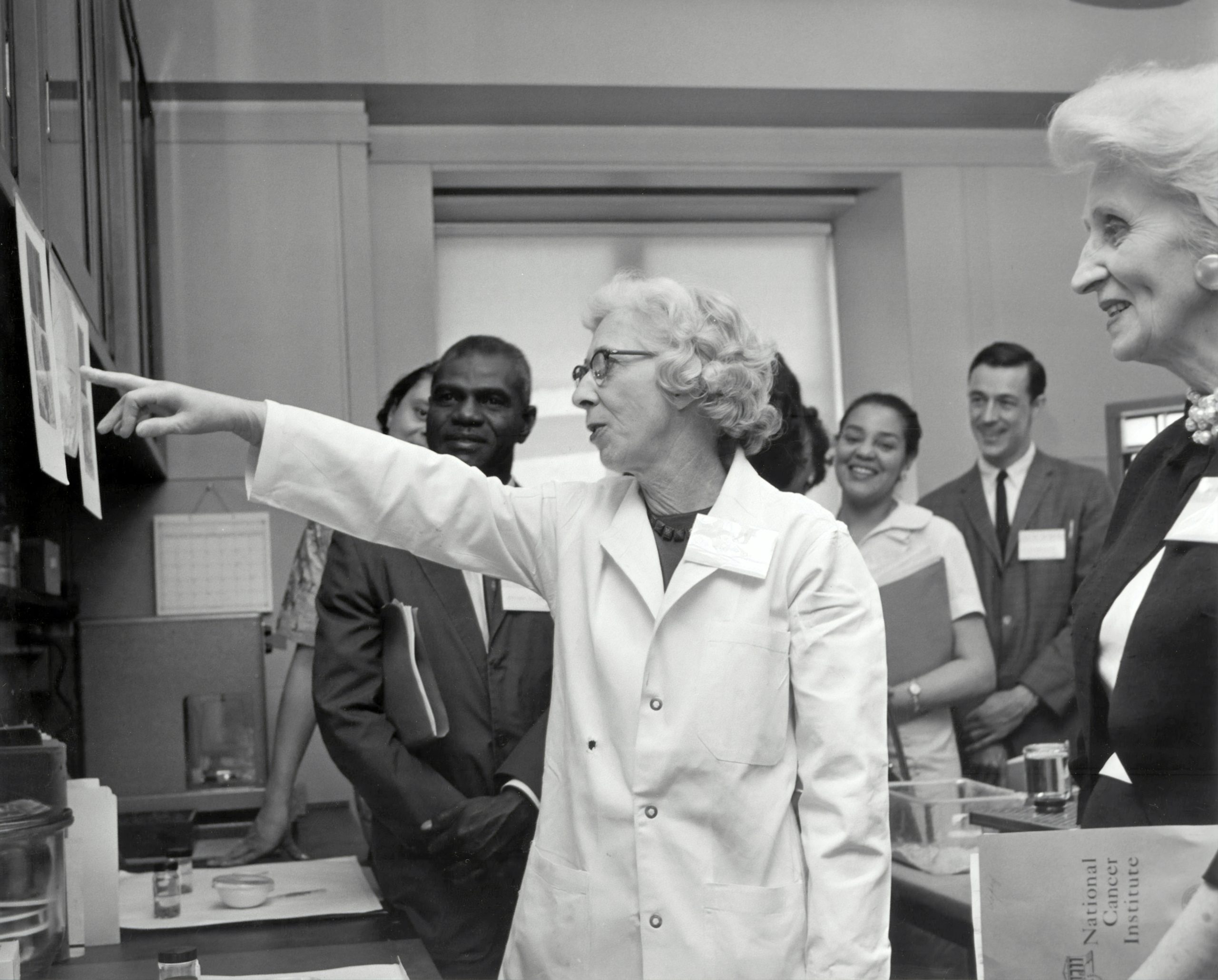

How the Ideology of Low Fat Conquered America Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Volume 63, Issue 2, April 2008 – Ann F. La Berge https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article/63/2/139/772615#13516940

And the book ‘Metabolical’ by Robert Lustig