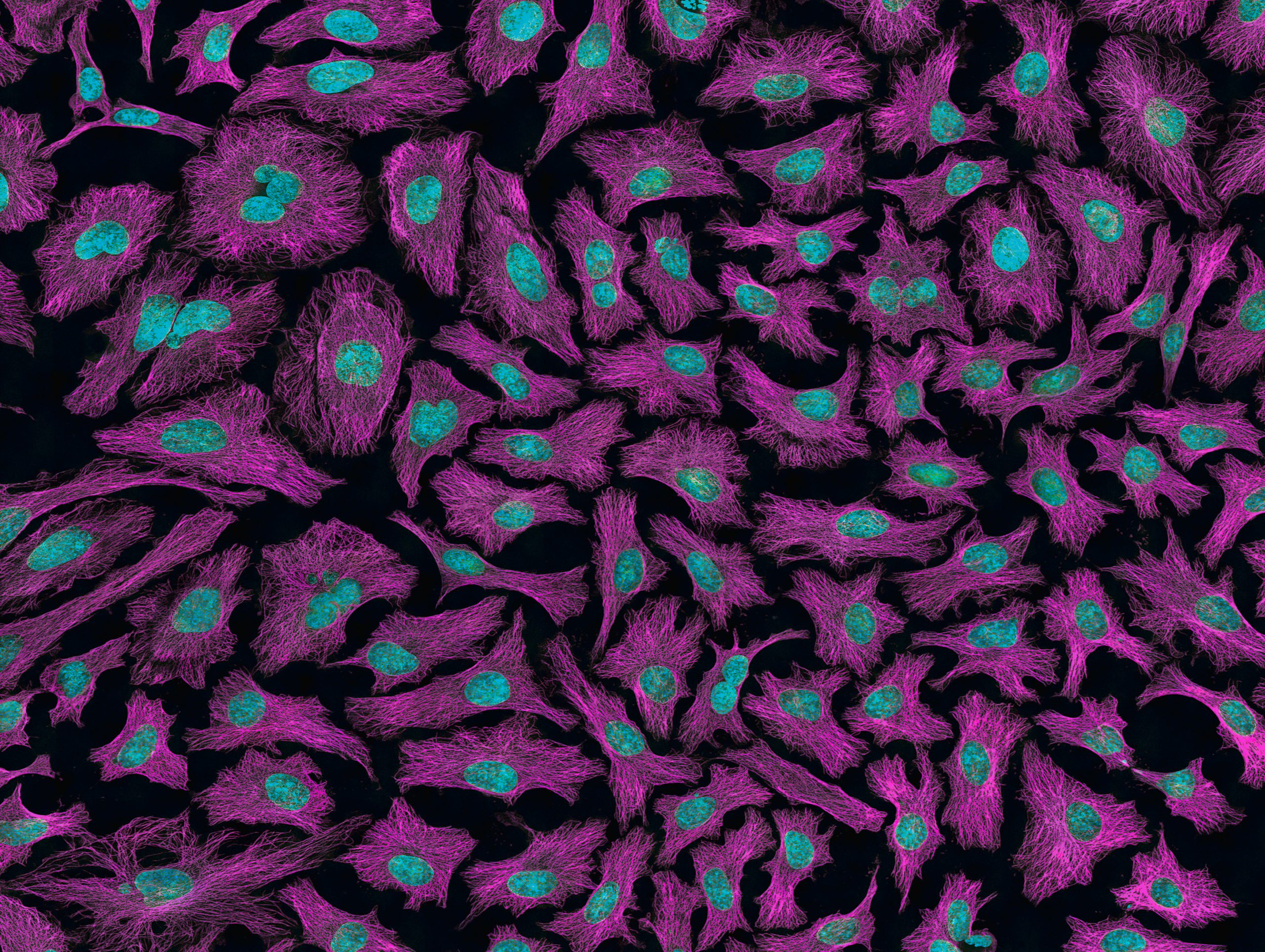

How can patent law help us define inventorship? Photo credit: National Cancer Institute via Unsplash

In this final article of our IP landmark cases series, we will explore a significant dispute between Yeda Research and Development Co. Ltd. (Yeda) and Rhone-Poulenc Rorer International Holdings Inc. (Rorer). This House of Lords (now the U.K. Supreme Court) case helped clarify the definitions of “inventorship” and resolve disputes regarding patent ownership.

Background: the invention

During the 1980s, scientists in the Department of Chemical Immunology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel were researching chemical treatments for cancer. Their experiments aimed to combine different treatments to create a synthesis more effective in fighting the cancer than any individual component. The researchers focused on monoclonal antibodies as the foundation of their work.

Antibodies are proteins produced by cells in the immune system called B-cells. On the surface of all cells are proteins used for cellular signalling, allowing them to migrate, grow, and activate specific functions. On cancerous cells, these surface proteins normally differ and are referred to as antigens. B-cells are activated to produce antibodies that bind cancer cell antigens, initiating processes that lead to cell death. Each B-cell produces a single type of antibody that binds to a specific part of an antigen, called the epitope. Multiple B-cells can therefore produce antibodies targeting different epitopes on a single antigen.

Each B-cell produces a single type of antibody that binds to a specific part of an antigen, called the epitope.

In 1975, it became possible to isolate monoclonal antibodies from a single ancestral B-cell and thus specific to just one epitope. These antibodies can be generated infinitely and are identical in structure.

In our case, scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science used monoclonal antibodies that targeted Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) receptors, found on cancer cell surfaces. These antibodies were cytostatic, inhibiting cancer cell growth without killing them. They combined this antibody with an antineoplastic drug which was cytotoxic, meaning it could kill the cells, This cell killing however included healthy cells, thus necessitating dosage limitations.

The Weizmann scientists first tested the antibody conjugated to the antineoplastic drug, with two controls: the antibody and the drug used separately; and an unconjugated mixture of the two. They discovered that the unconjugated mixture yielded significantly better results.

As they prepared to publish their findings, the scientists sent a draft to Professor Schlessinger, who was on sabbatical from the Weizmann institute. He was spending a year at Meloy Laboratories, which later became Rorer. He had previously supplied the scientists with two of the monoclonal antibodies used in their experiments, having developed them at Meloy. After reviewing the article, Rorer applied for a patent for the combination of antibody and drug, naming Dr. Schlessinger as the sole inventor. The European Patent was first granted in 2002. Yeda, the Israeli company to which Weizmann assigns the rights of its inventors, claimed that Rorer did not make the discovery and was therefore entitled to have the patent transferred to its name. This claim was first made in 2004.

Background: the law

Two key components of the legal discussion arose: key sections from the Patents Act 1977, and a significant 2005 House of Lords decision.

Subsection 2 describes that a patent can be granted primarily to the inventor or joint inventors, with provisions for legal agreements made prior to the invention.

Within the Patents Act 1977, two sections were crucial. First, Section 7, which outlines who has the rights to obtain a patent. Subsection 2 describes that a patent can be granted primarily to the inventor or joint inventors, with provisions for legal agreements made prior to the invention. Subsection 3 describes an inventor as the ‘actual deviser of the invention.’ Second, Section 37 provides a mechanism for resolving disputes about patent entitlement. Subsection 5 indicates that there are generally two years after a patent is granted to seek a court order to change ownership. If the current owner knew they were not entitled to the patent, the court could look into transferring it even after the two years. Rule 54(1) of the Patent Rules 1995 states that the person bringing the case must fill out Patents Form 2/77, accompanied by a detailed statement outlining the nature of the question, relevant facts, and the order sought.

The 2005 House of Lords decision in Markem Corp v. Zipher also played a significant role. In that case, Mr. McNestry, a former employee of Markem Corp, developed an inventive concept while working for Zipher, which filed several patents based on his work. Markem claimed entitlement, arguing that he had utilised information gained during his employment. The Court of Appeal ruled against Markem, determining that a person claiming entitlement to a patent must prove more than just inventorship; they must invoke another legal basis, such as breach of contract or confidentiality.

Legal reasoning

In March 2004, Yeda submitted the 2/77 form accompanied by a statement requesting joint proprietorship of the patent, and the addition of three Weizmann scientists as co-inventors. They provided evidence showing that the inventive contributions primarily came from Weizmann Scientists, while Dr Schlessinger had merely supplied the antibodies.

In response to Markem v. Zipher and further reflection, Yeda amended its statement to reference additional laws. They alleged that the draft had been sent to Dr. Schlessinger in confidence and that he remained a Weizmann employee during his sabbatical.

Yeda also sought to assert that Weizmann scientists were the sole inventors and that the patent should be transferred solely to Yeda.

These amendments were initially accepted, but after Rorer appealed, the Court of Appeal disallowed them, stating that the amendments constituted a new cause of action. According to Section 37 of the Patents Act 1977, the request to make the amendments was barred by the two-year limitation period. Yeda appealed leading to the House of Lords case.

The House of Lords faced several key questions: Firstly, could Yeda amend its claims after the two-year period? Second, what must Yeda prove? Third, did Yeda need to demonstrate that Rorer breached another rule of law?

The House of Lords addressed questions two and three together, first explaining that a person seeking to be added as a joint inventor bears the burden of proving their contribution to the inventive concept. To be substituted as sole inventor, they must also prove that the inventor named did not contribute to the inventive concept. The judgement clarified that Section 7 determines entitlement, requiring nothing more than being the inventor. Consequently, the House of Lords ruled that the principles established in Markem v. Zipher were incorrect, deeming Yeda’s first amendment unnecessary.

Regarding the first question, the House of Lords ruled that according to Rule 100 of the Patent Rules 1995, once the issue of entitlement had been referred to the comptroller (the head of U.K. Intellectual Property Office), the comptroller was authorised to determine the question of entitlement. This meant that even though Yeda amended its claim, the core issue of entitlement had already come before the comptroller, who was obliged to resolve it. It, therefore, did not matter whether Yeda claimed joint or sole inventorship.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the House of Lords ruled in favour of Yeda, recognising it as the sole owner of the patent, with the Weizmann scientists listed as inventors. This case was significant as it overruled the somewhat confusing decision in the Markem v. Zipher case and clarified what companies must establish to make claims of entitlement.

In this series, we have explored several landmark IP cases. We began with an introduction to Intellectual Property and examined its application through four pivotal cases. We looked at how courts deal with inventions that challenge our perception of novelty, how patents ensure healthcare remains accessible whilst also protecting innovators, and finally, what it means to be a true inventor.