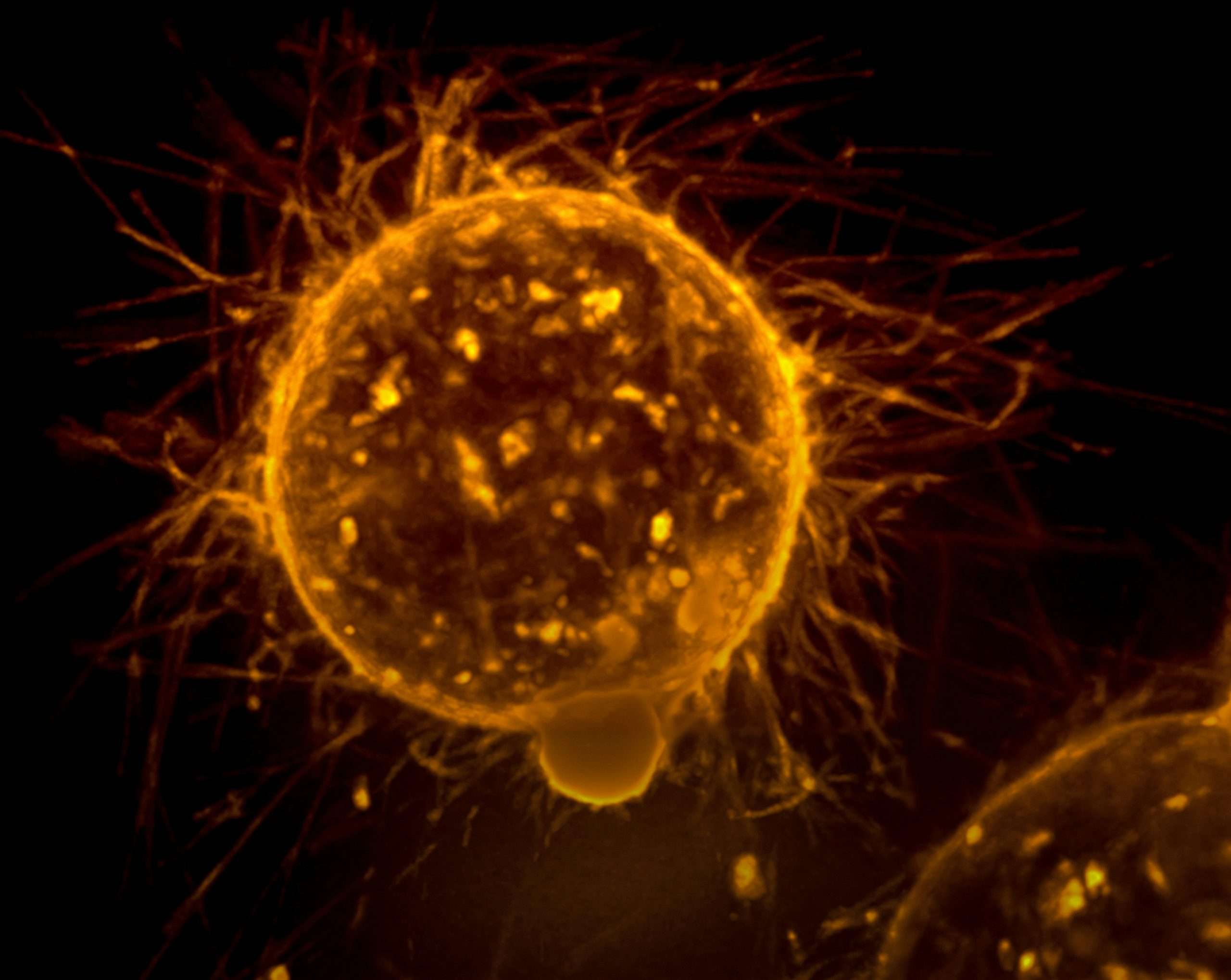

How can we harness our bodies to achieve cancer immunity? Photo credit: National Cancer Institute via Unsplash

‘Cancer is only a chapter of our lives. Don’t let it be the whole story’. Although some people are able to lead a cancer-free life, others might not be as lucky. It is scary to think that perhaps one day, the very cells that help you survive and exist will destroy your system from the inside out. Cancer has accounted for nearly 10 million deaths worldwide in 2020, and one in two of us will develop some form of cancer in our lifetime. Needless to say, this puts a massive financial strain on healthcare services worldwide, not to mention emotional stress on affected families and individuals. Without effective treatment modalities, the disease outlook remains as bleak as ever.

It is scary to think that perhaps one day, the very cells that help you survive and exist will destroy your system from the inside out.

When we think about “cancer”, the common misconception is that it will present the same way in every individual. Instead, it belongs to a debilitating group of diseases involving the uncontrolled proliferation and growth of cells with the potential to invade and spread to other parts of the body. In other words, although how cancer develops might be largely similar, its presentation across each person varies greatly. This unsurprisingly adds complexity to diagnosis and treatments. But what if I told you that your body has a natural defence mechanism against cancer? And that current research is working hard to harness this potential “silver bullet” to improve cancer prognosis? To understand this, we first need to look at how cancer arises in the first place.

What is cancer?

As we grow, the cells in our body need to divide to increase the size of our organs and tissues. These cell divisions are tightly controlled to maintain the correct cell composition and numbers so that each organ functions as intended. Each cell contains a nucleus, which is dubbed the “brain” of the cell. These nuclei contain genes (long strings of DNA) that encode signals, which instruct cells to behave normally. For example, genes control the number and frequency of cell divisions. When cells start to misbehave, in this case, if they begin to ignore signals and divide uncontrollably, the genes will code for signals that trigger a “suicide” program, which kills the cell via a process known as apoptosis.

This regulation works fairly well most of the time. As aforementioned, cancerous cells divide uncontrollably and do not get killed. This is mainly due to gene changes that govern cell division or the suicide program, known as mutations. Mutations can happen by chance when cells are dividing, or be caused by external factors, such as carcinogenic substances in tobacco smoke. That being said, cells are rather resilient to these mutations as they are good at repairing this damage. In addition, a single mutation is normally insufficient in cascading into such a catastrophic malfunctioning of cellular processes (unless it happens in a crucial gene). Nevertheless, if such damages accumulate due to repeated exposure to carcinogens, then there is a good chance that these will overwhelm the damage repair mechanism put in place, consequently causing uncontrolled division.

…a single mutation is normally insufficient in cascading into such a catastrophic malfunctioning of cellular processes…

Cancerous cells will divide and form an abnormal mass, called a tumour, and depending on its location in the body, this may press against nerve endings and cause pain. As tumours grow, they start to compete with surrounding cells for nutrients and oxygen, as well as breaking down surrounding tissues to make space for further growth. Once they hit a critical mass, tumours start to secrete signals that promote the formation of blood vessels. This occurs via a process called angiogenesis, which allows tumours to funnel nutrients from the bloodstream. At this point, part of the tumour may break off from the original mass and enter the bloodstream, which acts as a “highway” to other parts of the body and allows it to spread through a process known as metastasis. By using the information on the cancer’s growth dynamics, clinicians are able to work out the staging of cancer, which is imperative in informing treatment and care options.

Can our body recognise cancer cells?

Cells are quite honest about the state of their well-being. What this means is that they tend to announce how they are feeling directly to others, by displaying different proteins on their surface, helping the body look for these cells. Cancerous cells which proliferate at a rapid pace undoubtedly put themselves under a lot of stress, and this will be directly shown on the cell surface. For example, cancer cells tend to upregulate the expression of stress molecules MICA and MICB on their surface.

These molecules can be recognised by the immune system, which consists of a group of specialised cells (known as white blood cells), whose primary function is to defend the body against external threats such as bacteria and viruses. In this case, they are also able to recognise cancerous cells and eradicate them directly. Two cell types, namely cytotoxic T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, are exceptionally efficient at clearing up cancer cells. They routinely patrol and scan cells across the whole body for any signs of cancerous transformation. When they see these cells, they will kill them directly by force-feeding toxic substances (perforin and granzyme). Indeed, in certain cancers, such as melanoma, tumours which show good immune cell infiltration generally have a better prognosis (the likely course of a medical condition).

The immune system against cancer – a double-edged sword

Now, if the immune system is so good at what it does, why do we still get cancer? To explain this, we will draw on the example of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics have fully revolutionised the healthcare systems, making bacterial infections less deadly than they used to be prior to their discovery. They work mainly by inhibiting living processes within the bacterium, thus killing it. However, it is important to bear in mind that bacteria are living organisms, and over time they evolve to defend against these antibiotics, rendering them antibiotic-resistant. The more we use antibiotics to treat trivial infections, the faster this resistance arises in bacterial communities, and the harder it is to eradicate these bacteria.

…cancerous cells will mutate further and evolve mechanisms to escape being recognised by the immune system.

This is exactly what happens in cancer as well. Although the immune system would unsurprisingly gain the upper hand in its war against cancer initially, as time goes on, cancerous cells will mutate further and evolve mechanisms to escape being recognised by the immune system. This way, they will be able to develop much faster and spread to different body sites. In some cases, these cancerous cells are also able to shut down the immune system, either by inhibiting the effector functions or by preventing the migration of immune cells into the tumours directly. Cancer can also go one step further and manipulate and reprogram certain immune cells, such as macrophages, in order to promote tumour growth and metastasis. For example, tumour-associated macrophages can trigger angiogenesis and stimulate blood vessel formation into the tumours, further fuelling tumour growth.

Here, we can see that the immune system plays a paradoxical role in cancer. Despite its efforts to defend the body against it, it also indirectly promotes the evolution of cancerous cells into becoming more deadly, a process known as cancer immunoediting. This importantly highlights that cancer development is an extremely dynamic process, being able to bend even our own defence system to its will.

Can we harness the immune system to fight cancer?

As bleak as it may seem, this understanding of the interplay between cancer and the immune system also opens opportunities for medical research and new therapeutic targets. It is impossible to prevent cancerous cells from evolving under the pressure of the immune system, hence the idea here is to enhance the ability of the immune system to take out these cells, while at the same time preventing cancer from shutting them down. Normally, immune cells, such as T-cells, have built-in “brakes” that force these cancer cells to shut down post-activation. These “brakes” are known as immune checkpoints, with cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) being the most prominent examples. This process is crucial as it prevents the hyperactivation of T-cells which would consequently cause wide-spread inflammation, damaging innocent bystander cells and resulting in autoimmunity.

Cancerous cells evolve to take advantage of this feature, and to try to shut down immune cells by activating these immune checkpoints. If we could somehow stop these cancer cells from engaging these checkpoints, then we could free the immune system from being suppressed by cancer cells. The Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 2018 was jointly awarded to James Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their discovery of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which do precisely that. This idea then gave birth to the field of cancer immunotherapy, where we harness the power of the immune system to fight against cancer. Today, immune checkpoint inhibitors are being used as treatment for cancers such as lymphoma, melanoma, bladder cancer, and the list keeps growing.

According to Sun Tzu in The Art of War, if you know the enemy and yourself, then you will never be defeated. We have come a long way in our fight against cancer, and by dissecting the relationship between the immune system and cancer, we have unveiled novel therapeutic targets for future cancer treatments. The paradoxical role between these two components represents an exciting new discovery, allowing us to understand how cancer develops over time and becomes aggressive. Perhaps the day that we cure cancer completely remains out of reach, but at least now we can improve cancer-free survival, and diagnosis is no longer a certain death sentence as it was for decades prior. By understanding cancer better, we are one step closer to winning the fight against it.