How can we prevent further spread of the Marburg virus? Photo credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases via Unsplash

The main train station in Hamburg, the busiest in Germany, had several empty platforms on the 2nd of October. Two travellers had flown home to Germany from Rwanda and alerted German doctors that they had been exposed to Marburg virus. As a result, parts of the station were closed for fear of transmission. One day later, the travellers tested negative. Although Marburg virus has not yet infiltrated Germany, case numbers in Rwanda are growing day by day—but work is being done on developing a vaccine.

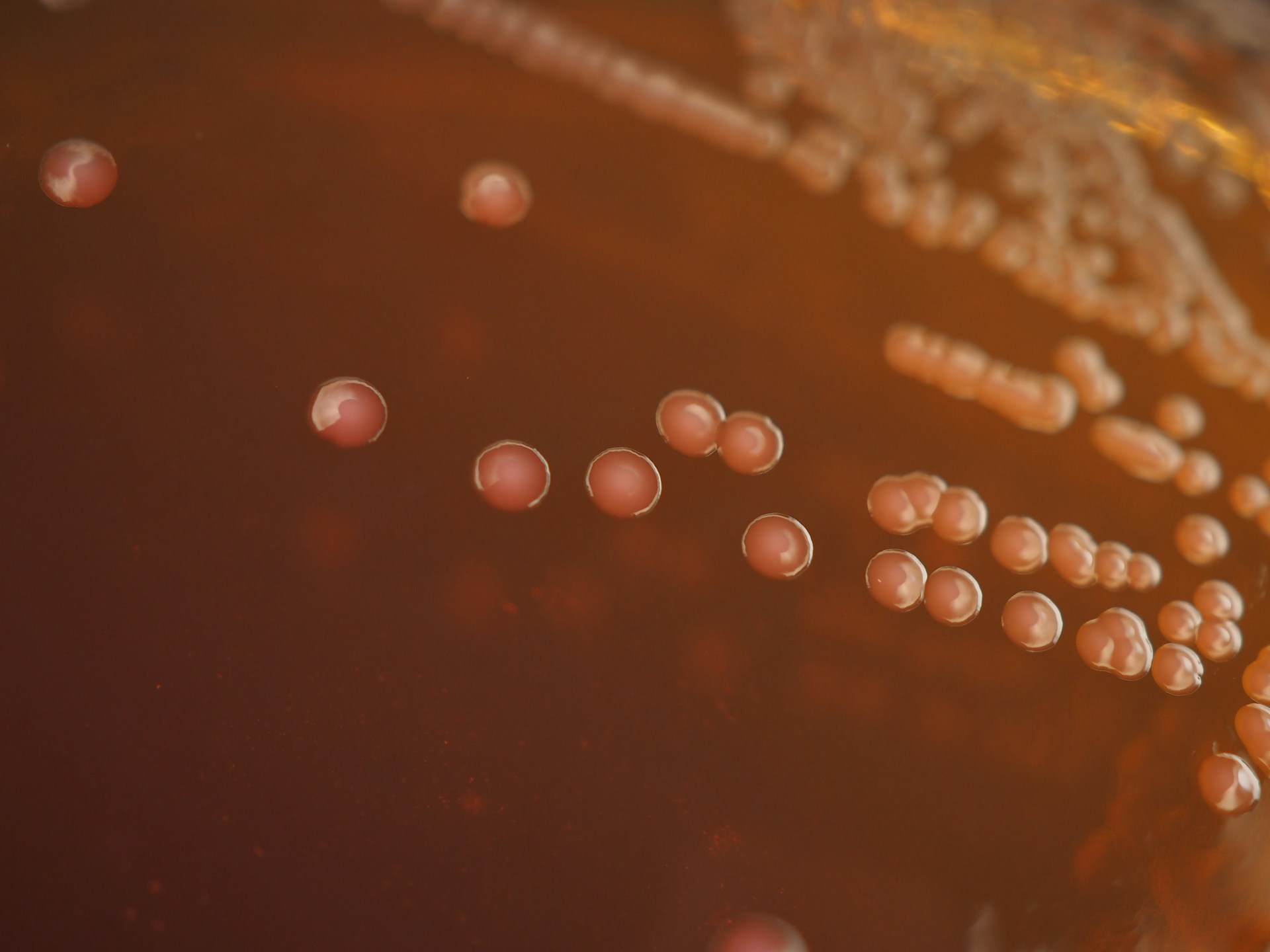

A person who contracts Marburg virus can develop symptoms within five to ten days.

The Marburg virus is a relative of the Ebola virus, both being filoviruses that cause haemorrhagic fevers which can be life-threatening. A person who contracts Marburg virus can develop symptoms within five to ten days. The first symptoms are quite generic: high fevers and malaise. The next day, symptoms can transform into severe diarrhoea and vomiting, and after a week, it can be fatal. The largest outbreak of Marburg to date has been in Angola in 2004, where out of 252 confirmed cases, there were 227 deaths—a death rate of 90%.

On the 28th of September, the health authorities in Rwanda declared to WHO that the country was experiencing its first outbreak of Marburg virus. Latest figures show that 58 cases have been confirmed with 13 deaths so far. Whilst most of the cases have been linked to healthcare workers who contracted it from direct contact with Marburg patients, there are some cases where the chains of transmission have not yet become clear—this could mean there are cases that haven’t been reported, or even detected.

Rwanda seems to be responding seriously and quickly to this threat. The country has had opportunities to practice its emergency public health responses and its response to COVID-19 was praised for its speed, effectiveness, creativity, and the value it placed on supporting people’s mental health. The Rwandan Health Minister Sabin Nsanzimana has said that anyone presenting with fever, head- or body-ache symptoms should be tested for Marburg and Africa CDC has provided 5000 tests kits to Rwanda and its neighbours.

200 people in Rwanda have already been vaccinated…

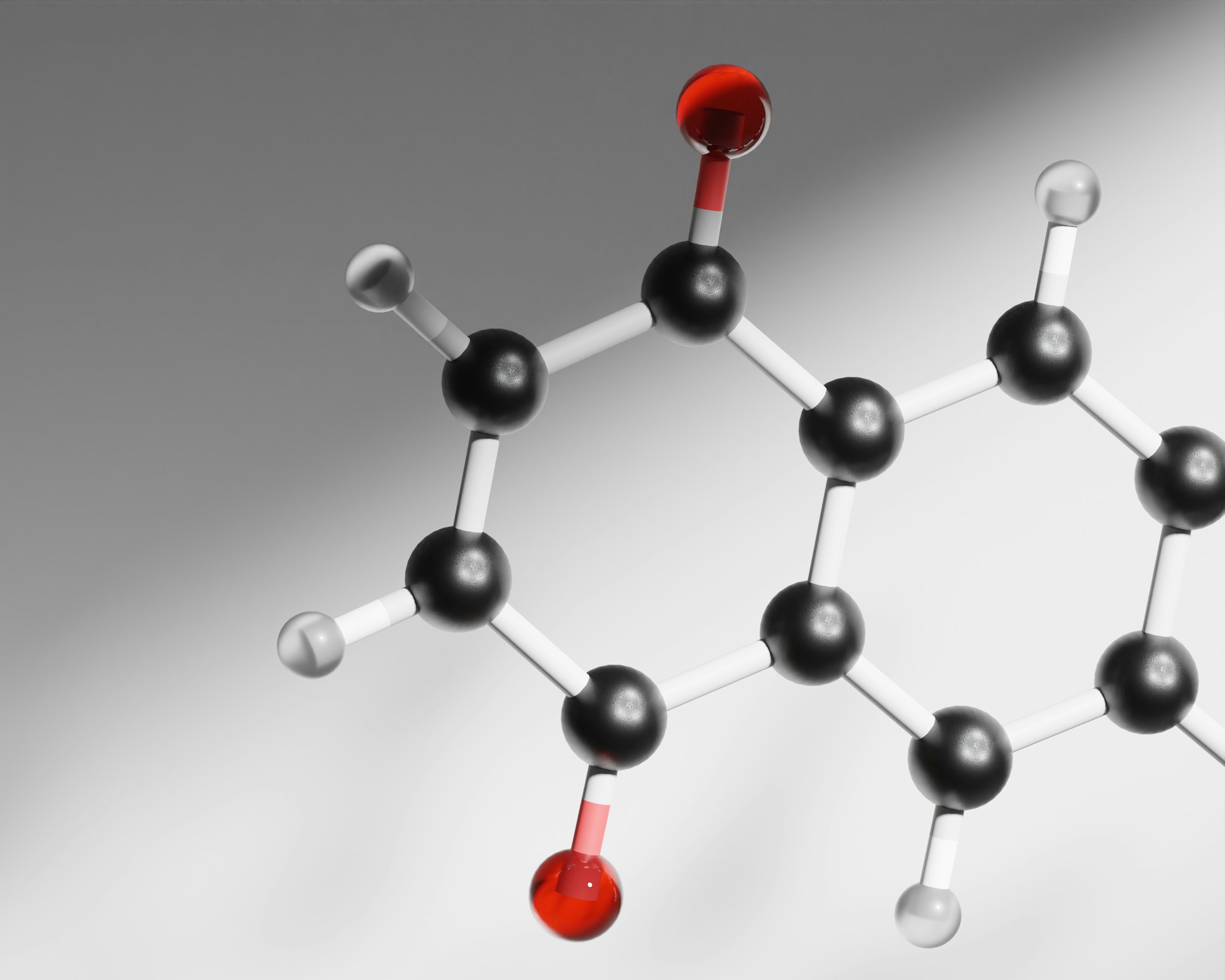

Although there is not yet a vaccine approved for Marburg virus, many are in the production line and 200 people in Rwanda have already been vaccinated using a phase II clinical trial vaccine that has been supplied by the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

Their vaccine works similarly to the Astra-Zeneca vaccine against COVID-19: a weakened chimpanzee adenovirus is made to carry the genetic material for producing the Marburg virus glycoprotein (GP). The adenovirus is then injected into the body, where it briefly infects cells and makes them produce the glycoprotein. This then causes an immune response, which hopefully creates antibodies and memory cells.

There are also other groups working on this challenge. Andrea Marzi’s group in Massachusetts is developing a Marburg virus vaccine using a similar principle with a vesicular stomatitis virus instead of a chimpanzee adenovirus.

Given that clinical trials are already running for some of these vaccine candidates, it is likely that Rwanda will employ a few of these. One of the challenges of using unapproved vaccines in emergency situations is the ethical dilemma of collecting rigorous scientific data, which ideally requires a placebo group, when the primary aim is to protect the population. This same challenge existed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and other outbreaks before that, and during these times, the standards of the data we collect will fall to allow us to be more compassionate in how we protect and look after people.

… our societies have hopefully become better at responding early and effectively to new outbreaks.

It is too early at this stage to say how significant the current outbreak in Rwanda will be on a global scale. But after the last few years, our societies have hopefully become better at responding early and effectively to new outbreaks. Managing the growing number of cases in Rwanda is not just the problem of the Rwandan government, but of the whole international community so that we pick up cases early, stop the disease spread, and work towards an effective vaccine quickly.