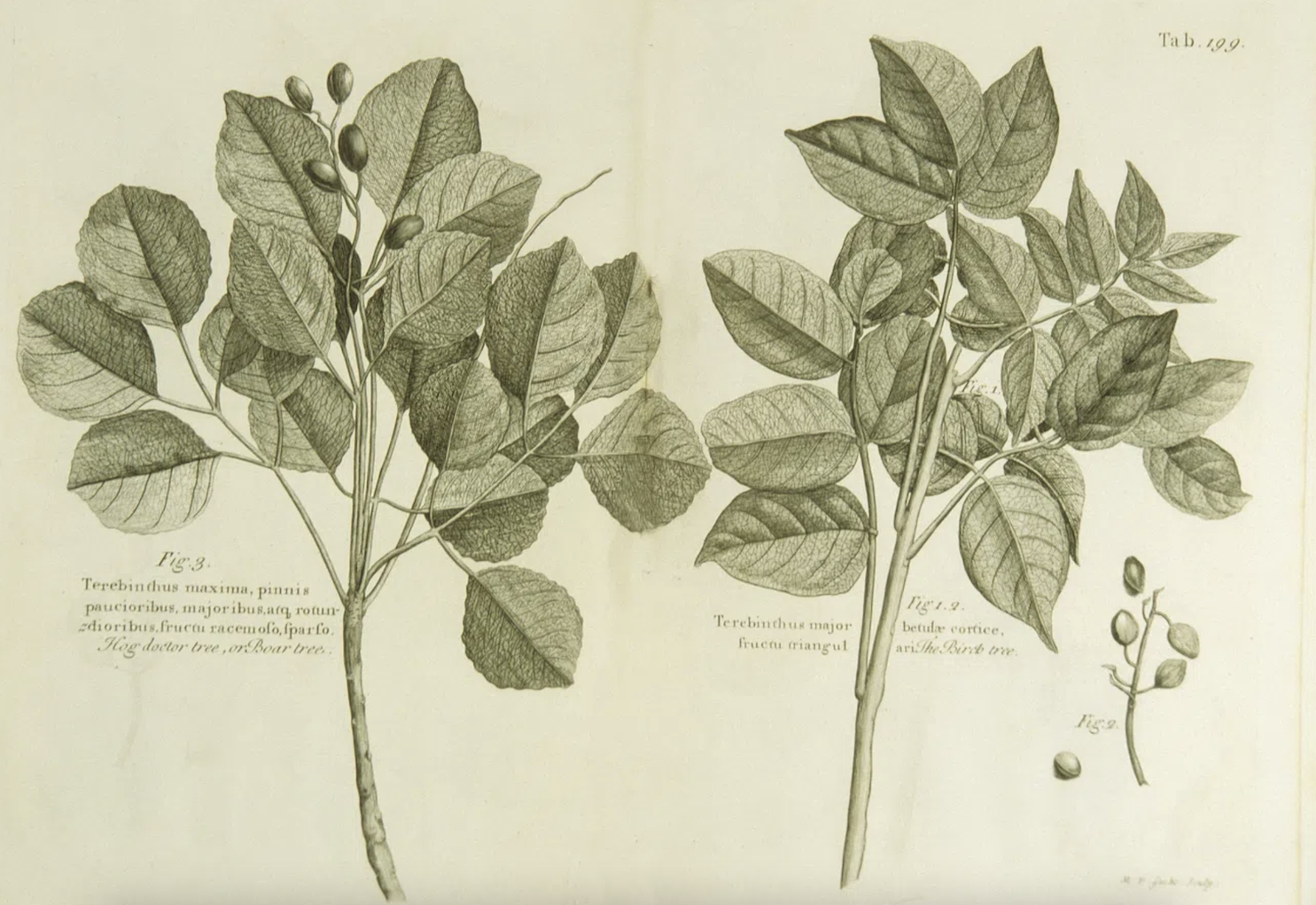

Exploring the scientific and cultural dimensions of traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine (TCIM). Image credit: Michael van der Gucht, Images from the History of Medicine, rawpixel, CC0.

All my life I’ve seen my dad, a well-read French man, who studied pharmacology at university, rely on homeopathy. He uses it to combat stress, nausea, pain, and more. I only began questioning it when I myself started studying science – is homeopathy really effective? Does a sceptic like my dad truly believe in it, without any doubt?

Over 80% of the world’s population, from all around the globe, reports wanting to use some form of traditional, complementary, or integrative medicine (TCIM), like homeopathy, for their health. TCIM includes a very wide variety of practices, from herbal remedies and acupuncture to yoga. TCIM is an official term of the World Health Organisation (WHO)—they define it as ‘the sum of the knowledge, skills and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health and the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness’. Examples include traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, originating from India, and acupuncture, as well as many other indigenous traditional medicines; all have their specific techniques and tools.

Over 80% of the world’s population, from all around the globe, reports wanting to use some form of traditional, complementary, or integrative medicine, like homeopathy, for their health.

The WHO held the first Traditional Medicine Global Summit in India in mid-August this year, following the creation of a WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine in 2022, also in India. The summit brought together science and policy experts, as well as traditional medicine practitioners and indigenous communities. They discussed the relevance of TCIM and ways to integrate it better into more modern healthcare systems. The expert panel organising the summit, following two days of discussion, published their conclusions in a report, the Gujarat Declaration. To summarise, they agreed to scale up efforts for appropriate integration of TCIM into healthcare systems, for example by increasing education surrounding TCIM and developing the evidence base supporting it. This would uphold the overarching WHO goal of universal health coverage. The declaration also highlights the importance of recognising the contributions of TCIM to modern medicine.

Indeed, 40% of pharmaceutical products currently on the market are thought to be derived from natural products or other TCIM practices. A classic example of this is the discovery of aspirin. Ancient scrolls from over 3500 years ago reference the bark of willow trees as a treatment used for non-specific pains by the Egyptians and Sumerians. In the 17th century, salicin was isolated from the willow tree as its active ingredient. Following multiple chemical modifications of salicin by different chemists, aspirin was eventually developed in 1897, thanks ultimately to the ancient knowledge of the power of willow tree bark.

Indeed, 40% of pharmaceutical products currently on the market are thought to be derived from natural products.

There are many such stories of traditional knowledge driving breakthroughs in modern science. Chinese scientist Tu Youyou, after years of researching anti-malaria drugs and 240,000 failed compounds, dove into traditional Chinese medicine literature for inspiration. She found references to sweet wormwood, used to treat fever, and eventually isolated artemisinin from it in the 1970s. Artemisinin is now a well-established antimalarial treatment.

Scientists are not the only ones to have seized on the promise of TCIM. Beauty influencers and social media health gurus are also making use of TCIM, under the cover of “lifestyle hacks” or other generation-appropriate labels. For instance, a recent TikTok trend praised the benefits of aloe vera, a component of traditional Chinese medicine, for everything from acne to digestive issues. TikTok is hardly a reliable source, especially when it comes to health, but I was still surprised to come across posts with bold claims such as ‘Tulsi—no cancer’. Tulsi, used in Ayurveda, is thought to contribute to a functioning immune system—but it’s far from guaranteeing a cancer-free life.

Just because something has stood the test of time, it does not necessarily mean it is clinically relevant.

Given the untrustworthy nature of such resources, it is understandable that some would question the efficacy and relevance of TCIM techniques. Although the WHO seems enthusiastic when it comes to tapping into the potential of TCIM, some still advise caution. Just because something has stood the test of time, it does not necessarily mean it is clinically relevant. The evidence base for some TCIM practices is flimsy at best. A review of 2938 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on TCIM carried out between 1980 and 1997 showed that the majority of these RCTs had methodological defects, with only 15% of them using appropriate blinding strategies for instance. Even in more recent years, the evidence has been lacking: most studies supporting the claims of traditional knowledge are non-clinical and carried out in vitro. Translation to humans might not be successful.

Homeopathy, despite its popularity, is one of the TCIM practices that has sparked the most debate. In 2017, NHS England resolved to stop funding homeopathy on the NHS, because of a lack of evidence for its effectiveness. Although the British Homeopathic Association argued that four out of five systematic reviews of RCTs in homeopathy demonstrated it performed better than a placebo (or dummy treatment), this claim was severely disputed. One of the so-called systematic reviews turned out to be a lecture series, one was re-analysed by its author and came out negative, and the others were either outdated or methodologically flawed. A more recent review compiled 110 reliable placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy, all following the standards for RTCs. Its authors concluded that ‘there was no convincing evidence that homeopathy was superior to placebo’. When I asked my dad about his use of homeopathy, he said that he relies on it solely because he believes in the power of the placebo effect. In his view, homeopathy works for him not because of any active compounds but because he trusts in the placebo effect’s ability to bring about results when he uses it.

Isolating active ingredients of plants and other compounds used in TCIM has been a challenge, and thus limited our ability to understand the mechanism of action of herbal medicines, and to appropriately test them in RCTs. Lack of standardisation in TCIM techniques is another issue that scientists need to address before building the evidence base supporting TCIM. Safety concerns are also to be considered: interactions between herbal remedies and drugs can have dramatic effects. St. John’s wort, a plant said to aid wound healing and have antidepressant properties, decreases the action of warfarin, an anticoagulant: this makes patients more at risk of developing blood clots, which can be life threatening.

Despite the sometimes-questionable evidence supporting TCIM, the shift of healthcare from a treatment-based approach to a more preventive approach would be well-suited to TCIM’s more holistic view of human health. TCIM tends to view human health as an entity, rather than separate it into discrete body parts or systems. This approach, which involves mind and body in the healing process, has become more and more appealing to many. Besides, new technologies are helping scientists tap into the potential of traditional knowledge. AI, bioinformatics, and other novel techniques can help assess the efficacy of compounds isolated from traditional herbal remedies in a more efficient manner. For example, gene editing has made it possible to shed light on the pain-relieving properties of acupuncture: a study showed that mice without the adenosine A1 receptor did not experience any analgesia (or pain relief) from acupuncture, nor did mice administered with an inhibitor of the A1 receptor. It is therefore thought that acupuncture stimulates the release of adenosine, a chemical involved in pain perception, which then binds to its A1 receptor to have its analgesic effect.

Besides, new technologies are helping scientists tap into the potential of traditional knowledge. AI, bioinformatics, and other novel techniques can help assess the efficacy of compounds isolated from traditional herbal remedies.

Because of the diversity of TCIM systems and practices, it is impossible to conclude whether TCIM as a whole is efficacious. Homeopathy seems to be no different from placebo, whereas acupuncture is backed by a more solid body of evidence and a putative mechanism of action. Some TCIM practices do seem to hold promise, as put forward by the WHO’s Gujarat declaration. The contribution of TCIM to modern medicine is undeniable, as is its importance for different Indigenous communities. However, the poor evidence base supporting some traditional knowledge should be considered with care: pharmaceuticals go through a very precise regulatory process being marketed, and such precautions should apply to any medicines. In the post-pandemic era, when patients want more autonomy regarding their health, significantly more research is required to fully make use of the potential of TCIM in an appropriate and reliable manner.