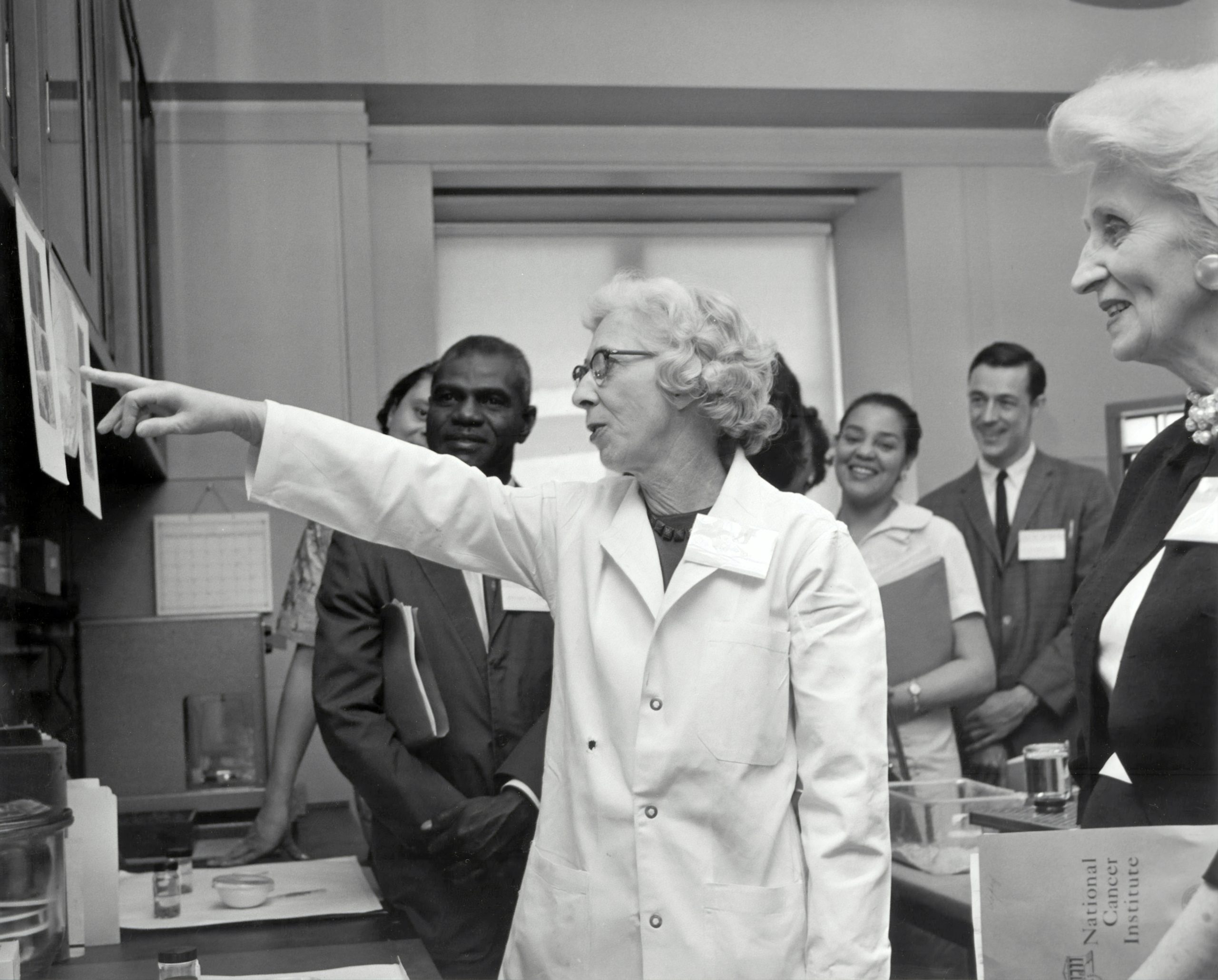

How can we improve barriers to diversity and accessibility in physics? Photo credit: National Cancer Institute via Unsplash

Though dark matter, the fate of the universe, and quantum gravity are all important problems within physics, one unsolved question tends to be bypassed. In many STEM subjects, but physics especially, there is a concerning lack of diversity in terms of social structure. Much of this underrepresentation stems from the falsehood perpetuated throughout the educational system that physics is a “male subject”. From early education to choosing to pursue physics at an undergraduate or career level, the retention of women diminishes at an alarming rate. This article uses gender as an example but aims to not detract attention from the barriers that apply to all underrepresented demographics within science. Diversity within any scientific discipline encourages innovation.

…there is a concerning lack of diversity in terms of social structure.

Early years and the education system is the first step of presenting a career in physics as a viable option for women. The equal capabilities of children at a young age proves that it is sociological bias that tends to hinder girls from pursuing physics, as opposed to inability. The ‘draw a scientist’ study is a famous representation of this ingrained bias. The original study took place over a period of ten years, and as its name suggests, simply asked young children to draw a scientist. Out of the nearly 5000 asked, 28 children, none of which were boys, drew a female scientist. The rest of the drawings depicted features of the stereotype that is still perpetuated in the media of an old, white haired, lab coat wearing scientist. This image, if continued to be imbibed throughout childhood, damages the perception of those that are excluded from the archetypal image, such as women or people of colour.

Out of the nearly 5000 asked, 28 children…drew a female scientist.

Throughout the early years, and even up to GCSE, girls and boys display the same aptitude for mathematical or science-based skills, such as number processing. There is overwhelmingly inconsistent evidence of differing skill sets between men and women: for example, one study claims that men perform better in spatial ability and problem solving, whereas another study wrote that the female brain outperforms in algebraic and pattern recognition-based problems. These statistically insignificant nuances are overshadowed by the driving piece of evidence that ‘experience alters brain structures and functioning, so causal statements about brain differences and success in math and science are circular’. The way in which physics is taught and perceived has a major impact on the lack of retention of female students when they choose whether to continue studying physics or not. Teachers risk alienating girls from the subject by only using male examples of physicists, or by portraying or reinforcing the myth that men outperform women in all areas of mathematical cognition.

By A-level, the gender disparity has widened to women only making up 23% of physics students. The trend continues at undergraduate level, where the percentage of women admitted into the University of Oxford to study physics, for example, was 19.8% between 2021 and 2023. The cycle, and the stereotype it preserves, is self-perpetuating. In most physics departments, only one in five academics are female, and so female job applicants lack role models or any persuasive evidence that physics is a field they could see themselves in. These statistics have increased marginally in the past few decades, showing stasis where there should be immediate change. Not only are the ratios highly imbalanced, but women within STEM still tend to earn less than their male counterparts. The stagnancy in the gender composition of academics and published researchers means that it is predicted to take as long as a century or two to reach parity.

After deciding physics is a feasible career path and pursuing it through higher education, women may struggle more than men to make headway within the field. In a paper published by Jacob Blickenstaff, the term “leaky pipeline” was coined to describe the loss of capable individuals, especially women and those from underrepresented backgrounds, from academic careers. The lack of retention of female scientists can be majorly impacted by bias, as well as issues of self-esteem and interactions with peers or mentors. Although imposter syndrome is a universal affliction, it tends to affect the career trajectory of a woman in STEM more. This is often attributed to ‘women being more likely to be uncomfortable with their success…[perceiving] success in certain spheres as a masculine accomplishment’.

In some cases, this imposter syndrome is both internally and externally motivated. There are countless examples of female scientists omitted from the discourse of history because of lesser recognition compared to their male counterparts. Physicists, such as Jocelyn Bell and Vera Rubin, who played indispensable roles in research into radio pulsars and dark matter respectively, were overlooked for Nobel prizes in those areas. Jocelyn Bell has since been awarded the Breakthrough Prize and donated her £2.3 million winnings to counter the ‘unconscious bias’ she believes is still present within physics. Giving a voice to people such as these women and addressing the issues of discrimination will help to plug the “leaky pipeline”.

In order to achieve equity, female scientists should continue to be celebrated.

A holistic approach to the issue of diversity of physics would also consider the way it is taught in schools. To improve accessibility, it should be seen as a subject in its own right and the curriculum should include its relevance to the wider world. In order to achieve equity, female scientists should continue to be celebrated. They must be included in the curriculum so that from a young age, girls have role models to look up to. This will combat unconscious bias, both in the students themselves and in the teachers and parents who influence their educational path. The Institute of Physics has recently launched the Limit Less campaign which provides resources for educators in an attempt to examine and dismantle the barriers that prevent young people from choosing to study physics. Implementing inclusive measures, such as this campaign or outreach programmes for skills like coding or laboratory, helps to make physics accessible to people of all identities and backgrounds.

The public perception of a physicist remains archaic and, as a result, physics remains inaccessible.

The public perception of a physicist remains archaic and, as a result, physics remains inaccessible. As it stands, the gender imbalance means that physics omits half of the population that it could be appealing to. Lack of diversity within physics may be detrimental to innovative theoretical thinking. For example, as the field of particle physics progresses into the bizarre world of string theory, the problems that remain unsolved must be approached from a multiplicity of angles. Academic culture must nurture collaborative and creative approaches that will flourish within diverse workplaces.

In order for women and underrepresented demographics to want to engage with physics, there must be more role models and encouragement that it is a discipline where women are equally valued. This is implementable at all stages of education, and especially important at periods in which students may be dissuaded from choosing physics. Teachers must work to dispel any misconceptions surrounding physics-based careers, and present an updated view of the subject. More can be done to shine light on individuals from underrepresented groups who have contributed to physics and data on the lack of diversity in physics should be made as transparent as possible.