Carmen Dupac, Year 12, Twynham School

Science is not often regarded as a creative subject; most wouldn’t consider it to be creative at all. After all, science relies on scientific methods and credibility, statistics and data, tests and hypotheses – all things that seem to eliminate creativity. But what about the areas where creativity is quite literally part of one of the most heavily explored areas in science? The brain.

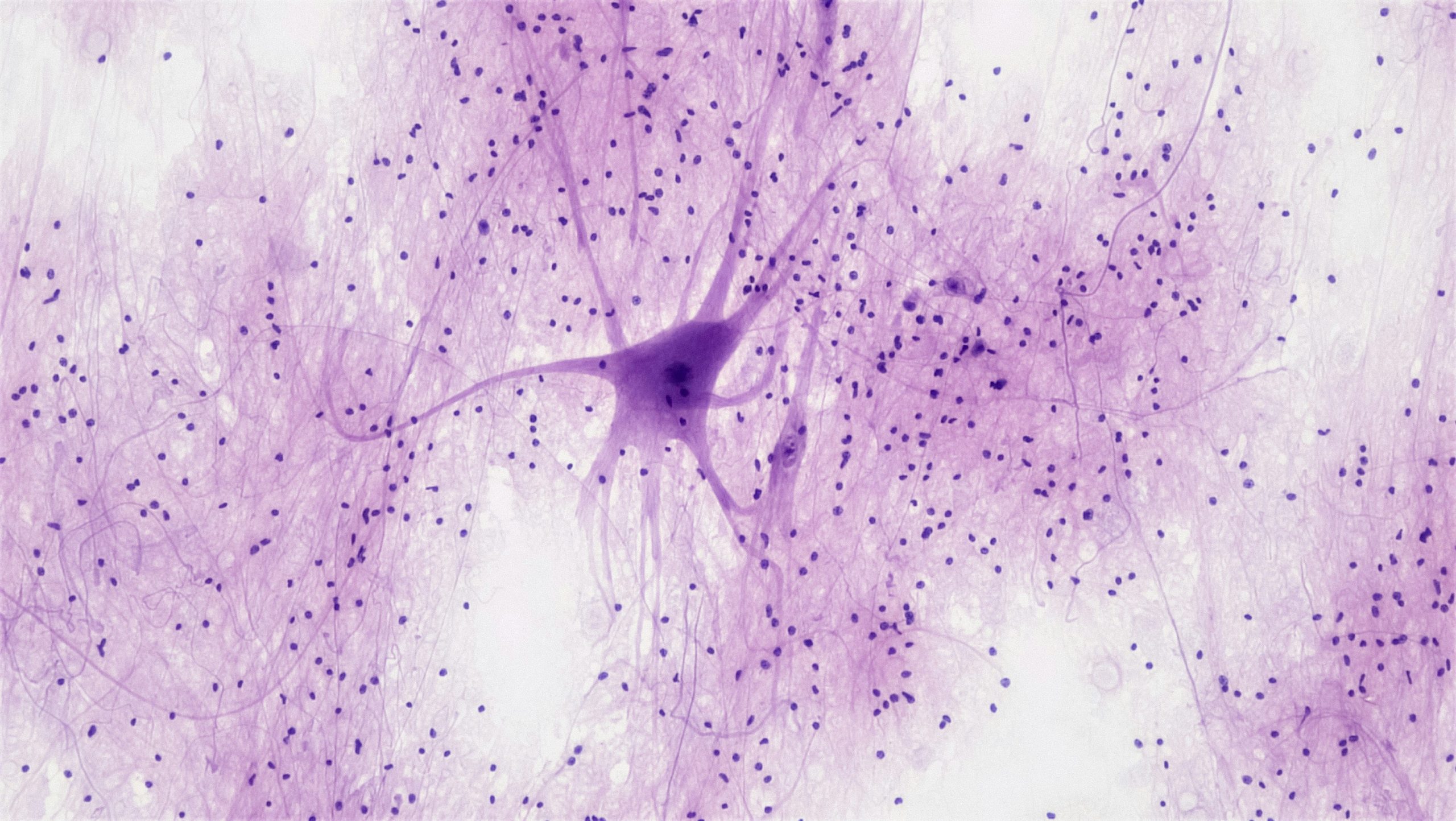

Arguably the most important organ in our body, the one that makes us human, the brain comprises 2 hemispheres, 4 lobes, 12 cranial nerves and an estimated 86 billion neurons. So where does creativity come into play? Well, our brain is divided into two hemispheres; the right and left. Old theories and models allude to the left brain managing our analytical thinking and logic, whereas our right brain rules over our imagination, and hence our creativity. However, this is an overly simplified concept. Advances in neuroscience show that the origin of creativity in our brains is a lot more complex than originally thought to be.

A 2017 study by Roger E. Beaty began to unveil the synchrony between distinct networks in the brain. “One thing I hope this study does is dispel the myth of left versus right brain in creative thinking” – Beaty (2017). In his study, 163 participants underwent fMRI scans whilst performing a creative thinking task, where they had to devise an imaginative use for an otherwise common object – such as a cup, or paperclip. Such a divergent task reflects real-world thought processes, especially in the sciences. Upon examination of the brain scans, Beaty discovered that the creative thought process correlated with brain activity in 3 distinctive, large-scale systems: the default mode network, the executive control network, and the salience network. Three systems that interacted intrinsically and dynamically, to provide a pathway for the creative processes that we utilise every day.

That interaction goes a little something like this. The Default Mode Network is primarily responsible for ‘idea generation’ and achieves this in the form of daydreaming and brainstorming when the mind is not performing another task. Contrastingly, the Executive Control Network targets attention and concentration. Its connections with the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making, allows for the maintained focus upon a new creative thought. Further connections to Parietal regions allow the brain to access and utilize sensory information to allow for ‘idea evaluation’, be this in the strumming of a new song on a guitar, or the imagined smell of a new recipe. It is the combined collaboration of these two networks that generate creativity. The Salience Network (SN), the final piece of the puzzle and perhaps the most crucial system of them all, is implicated in facilitating the transmission of information between the previous two systems. When solving a problem, the SN decides which piece of information is most proficient in doing so, and sifts through the copious amounts of sensory information that we constantly receive, to detect and relay only the most relevant stimuli.

Participants who came up with more creative, unusual, and out-of-the-box ideas during the divergent thinking task, indeed had brains that made more and faster connections between the three systems. Ergo, those who have a more creative brain can engage those networks in ways others simply cannot.

This all brings me back to the subject at hand. Is creativity important in science? To put it simply, how can it not be when creativity is itself a science. If this complex yet fascinating array of interactions did not exist, how would we make scientific advances, discoveries, innovations? If Alexander Graham Bell’s default mode network wasn’t around to allow his mind to successfully generate ideas, would we have the luxury of face timing friends and family to catch up amid the current pandemic?

Would we have the amenity of vaccines and endless medication for our every need if creativity wasn’t shooting through the 68 billion neurons of diligent scientists? Creativity is not important in science, it is essential.

Runner-up for the Schools Science Writing Competition, Hilary Term, 2021

Image credit: Meo via Pexels