Brain waves underpin all brain functions. Whether these functions extend to consciousness, and if brain waves are a measure of such is debated. Photo credit: Yasmin Azizbayli, The Oxford Scientist

If you have ever wondered what is happening to your brain when you find your mind blank or start to daydream, you need look no further than low-frequency brain waves. Commonly referred to as ‘slow waves’ or ‘delta waves’, this electrical activity is commonly associated with sleep but they can also intrude on the awake mind, causing lapses in attention. But, slow waves are not the only brain wave, and certainly not the only waves involved in consciousness.

Brain waves are defined by the technology used to measure them: in other words, as the bands of frequencies seen through electroencephalography (EEG) recordings. EEG electrodes placed on the scalp pick up the firing of neurons below, and the signal from billions of cells fluctuates over time.

Ordered from high to low frequency, you can distinguish gamma, beta, alpha, theta, and delta waves in this manner. This veritable Greek alphabet has been associated with almost every cognitive process, including attention, memory, movement, and perception, despite being initially written off as background noise. As higher frequencies are associated with being awake and alert, gamma/beta/alpha waves are more associated with processes such as concentration. Increases in the higher frequency bands in specific areas of the brain are also present when you dream.

Not only are slow brain waves inherent to sleep but also loss of consciousness in other forms, such as anaesthesia or coma. In such states, neural activity flip-flops between intense firing and periods of no firing, known as ON- and OFF-periods. This is thought to affect consciousness by disrupting the coordination between brain regions physically far from each other.

Having similar wave activity may suggest that these areas are involved in the same process and perhaps this coordination is necessary to select particularly relevant information for processing, bringing them into our current awareness (our working memory). Meanwhile, the ON-/OFF-periods of sleep cause a breakdown in this selection due to the intermittent periods of complete silence, dissolving our living experience.

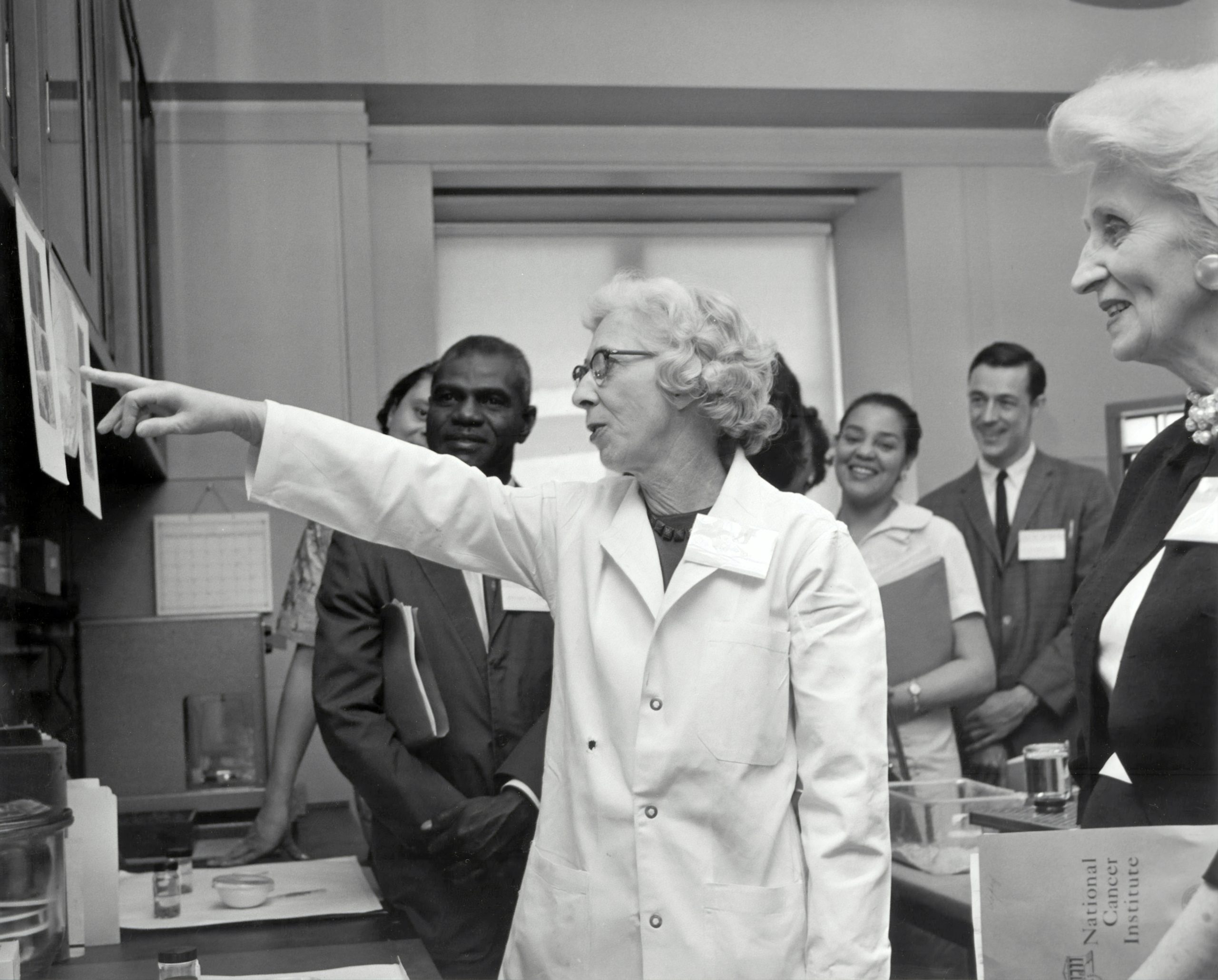

From this, it may be possible to use wave recordings as a measurement tool in patients with disorders of consciousness, for example those in comatose states following brain injury. Still, this is a controversial avenue due to the debate surrounding the “hard problem” of consciousness” described by David Chalmers in 1995. This is the idea that even if we have the biological building blocks of perception (solving the “easy problem”), we will still need to answer ‘what it is like’ to have a conscious experience, to decide if brain waves correlate accurately.

…it may be possible to use wave recordings as a measurement tool in patients with disorders of consciousness, for example those in comatose states following brain injury.

According to some, the answer is quite simple: as our understanding develops, the problem will resolve itself. One advocate of this is researcher Anil Seth who, in a recent Oxford consciousness conference, equated this question to that of why the universe or life exists. Seth argued that these questions, once daunting to physicists and biologists, have been progressively reframed over time into terms solvable by scientific understanding. The hard problem of consciousness will follow suit.

…we may aim to develop machine consciousness to prove we understand its underlying principles. But whether we can then determine if it is truly conscious is unknown.

It may be true that we simply lack the foundation to comprehend the question at present. Yet, there are others who disagree and call for a radical overhaul in science to address these questions fully. For example, we may aim to develop machine consciousness to prove we understand its underlying principles. But whether we can then determine if it is truly conscious is unknown.

The study of brain waves may provide a means to understanding the functional biology underlying consciousness, potentially providing an objective measure for diagnosis otherwise limited by the subjectivity of human description. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if we are currently even able to truly define “consciousness”.