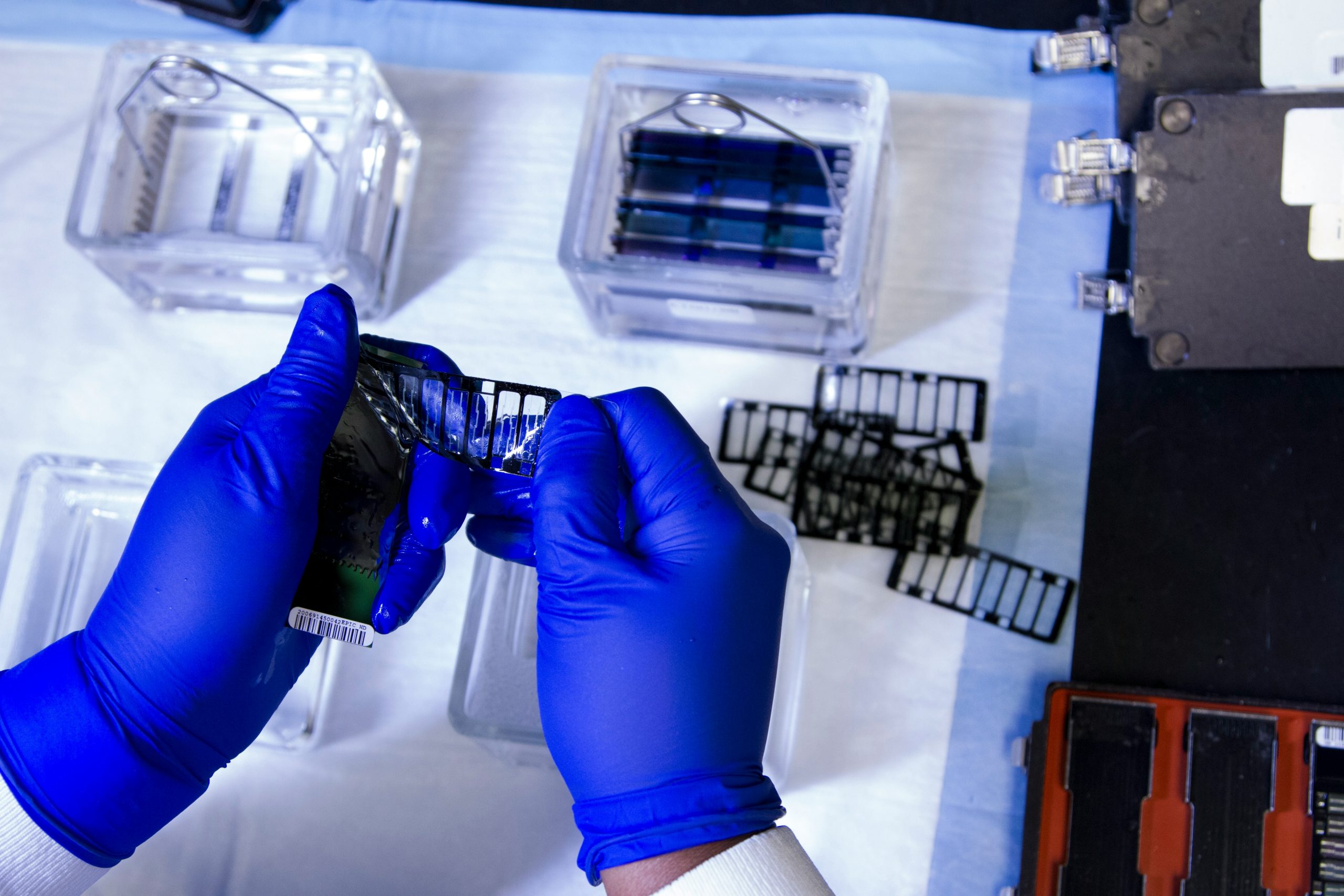

Are genetics able to patented under IP law? Photo credit: National Cancer Institute via Unsplash

In the previous article, we learned that microorganisms created by human ingenuity can be patented. Here, we explore the case of Association of Molecular Pathology (AMP) v. Myriad Genetics, Inc. (Myriad), in which the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decided whether or not an isolated sequence of DNA can be patented.

Background: basic science

To fully appreciate this groundbreaking case, it is essential to understand the basic structure and function of DNA. Inside cells, DNA is made up of two long strands of molecules (nucleotides). These strands run in opposite directions and are held together by strong bonds. Each nucleotide contains a sugar (called deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and one of four organic bases: Adenine, Guanine, Thymine, and Cytosine. Base pairing rules ensure that Adenine and Thymine are always bonded, while Guanine is always paired with Cytosine.

The sequence of bases along the DNA encodes genes.

The sequence of bases along the DNA encodes genes. Genes are transcribed by an enzyme into a similar molecule called RNA. This is then translated into protein molecules that can carry out molecular and cellular functions. Each gene contains coding sequences (meaning they code for amino acids which ultimately make up proteins), called exons, interspersed by non-coding regions of DNA, called introns. When a sequence of DNA is synthesised in a lab, it normally only contains the exons and is referred to as complementary DNA (cDNA). Mutations, or alterations in the base sequence, can result in changes in amino acid sequence, and therefore, protein structure and function, which may amplify the risk of disease.

Background: Myriad Genetics

Myriad Genetics was founded in 1994 by scientists from the University of Utah following research from a few years prior which revealed the BRCA1 gene location. Mutations in the gene BRCA2, which was discovered later, are both associated with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Using this discovery, Myriad filed three types of patent claims (see this article to refresh on the IPLC definitions): claims over the isolated DNA sequences, method claims to diagnose propensity to cancer by comparing mutated DNA sequences to the non-mutated sequence, and to identify drugs using the isolated DNA sequences. These patents would afford Myriad exclusive rights to isolate an individual’s BRCA genes, as well as the exclusive right to synthesise BRCA cDNA.

These patents would afford Myriad exclusive rights to isolate an individual’s BRCA genes, as well as the exclusive right to synthesise BRCA cDNA.

Myriad’s entire business model involved offering diagnostic testing services for BRCA genes. Investors funded the company based on the 20-year duration of a patent, allowing Myriad to charge a premium price for their services. Myriad, therefore, enforced its patents very strictly. For example, in 1988, Myriad sent the University of Pennsylvania’s genetic diagnostic lab a cease-and-desist letter, which insisted that clinical pathologists stop testing patients for BRCA mutations. Because of the threats this demand posed to its members, the AMP campaigned against the exclusive licensing of gene patents and was the lead plaintiff in the SCOTUS case.

Legal Reasoning

On 13 June 2013, the nine judges in SCOTUS unanimously decided that a naturally occurring DNA sequence is a product of nature and not patent-eligible simply because it had been isolated. Nonetheless, cDNA is patent-eligible despite containing the same base pair sequence as the naturally occurring exons.

…a naturally occurring DNA sequence is a product of nature and not patent-eligible simply because it had been isolated.

The main legal issue revolved around article 101 of the Patent Act. It states, ‘whoever invents or discovers any new useful…composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.’ It had been established in previous SCOTUS cases that this article contains an exception. Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable (see previous article which addresses this ruling). If patents were granted for these, it could prevent other researchers from accessing important discoveries thereby inhibiting innovation––which directly contradicts the purpose of patents. Myriad did not discover any new genetic information, but simply revealed the location of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes using methods already known to geneticists. This stands in contrast to Chakrabarty, who had modified a strand of bacteria to create a new, non-naturally occurring function.

Similarly, SCOTUS dealt with patents involving products of nature in the 1948 case of Funk Bros. v. Kalo Inoculant Co.. Here, SCOTUS considered a composition patent that claimed a mixture of naturally occurring strains of bacteria could help plants fix nitrogen. Bacteria had been used by farmers for a long time, who often inoculated their crops with them to improve soil nitrogen levels. Each crop was only able to form a mutually beneficial relationship with one type of bacteria. Ideally, farmers would be able to use a single inoculant containing many strains of bacteria, simplifying the purchase and distribution of inoculant. This proved very difficult to invent since the bacteria inhibited each other. This new mixture of bacterial strains aimed to overcome this issue. The court ruled that this new mixture was also a discovery rather than an invention since they had just combined naturally occurring bacteria rather than creating a new invention.

To counter this ruling, it was claimed that the isolation of DNA from the human genome required chemical bonds to be broken, which therefore created a non-naturally occurring molecule. Myriad’s claims, however, were primarily concerned with the information contained within the genetic sequence and not the chemical composition of a molecule. If Myriad were concerned with chemical composition, a would-be-infringer could avoid Myriad’s patent claims by isolating a DNA segment containing both BRCA genes plus a single extra nucleotide. Myriad, of course, would not want this.

Since cDNA, only contains exons, it is a non-naturally occurring molecule. Whilst cDNA does use a sequence derived from the naturally occurring DNA sequence, it has been changed significantly through the removal of introns and is therefore not a product of nature.

Since cDNA, only contains exons, it is a non-naturally occurring molecule.

Impact

This surely accelerated advancements in genetic diagnostics and cancer research.

The case of AMP v. Myriad had far-reaching consequences. First, SCOTUS created a clearer framework for defining what is a patentable subject matter. This led to a large review of existing patents of naturally occurring molecules, in particular genes, and to a shift in the way biotechnology firms approach patents, moving towards more synthetic products. Second, the ruling opened the BRCA genes for use by other researchers. Previously, they would have required licensing, but now they could carry out genetic research and testing. This surely accelerated advancements in genetic diagnostics and cancer research. From the patient’s perspective, the newfound competition was able to drive down the cost of genetic testing. Finally, this ruling reinforced the fact that DNA, shared by all living organisms, should not just be owned by a single company. This ruling was, therefore, also a large ethical success.

In the next article, we transition away from American case law and look at a landmark case from the European Patent Office that answers the key question of whether any type of surgery can be patented.