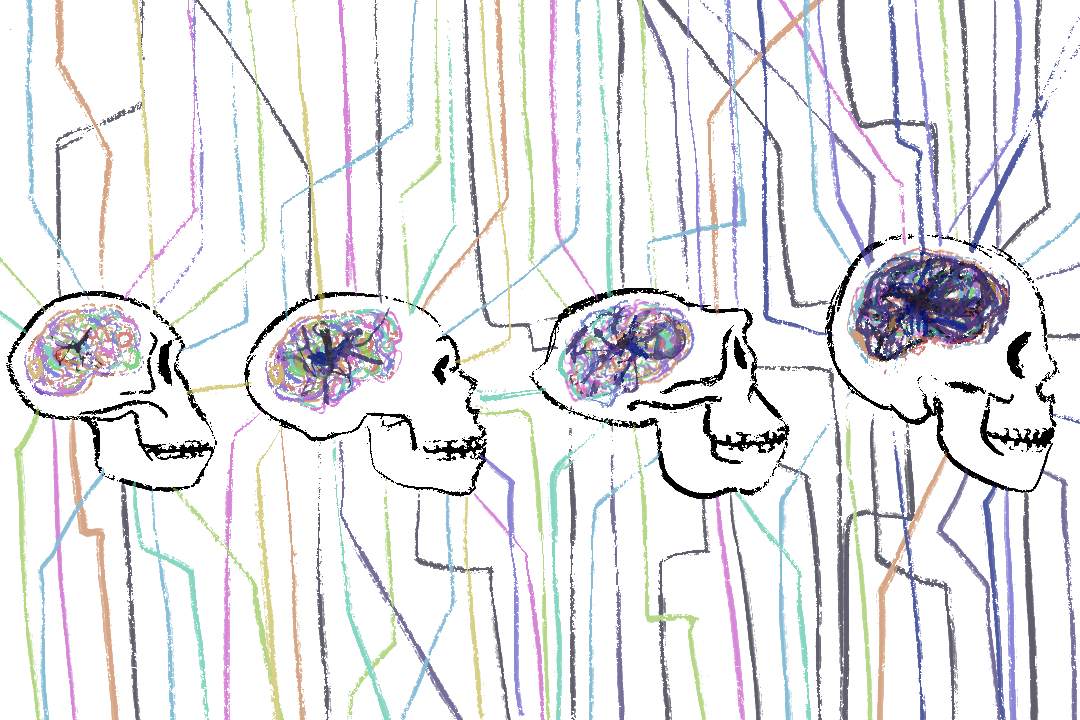

Is there an evolutionary basis for depression that drives its prevalence amongst populations? Photo credit: Niamh Walker via the Oxford Scientist

We treat the symptoms of depression – loss of motivation, profound emptiness, and spiralling self-esteem – as the problem. This is an intuitive approach; since the symptoms are what cause the suffering, these are the problems that we need to solve. But what if this were not the case?

In 2019, 280 million people were estimated to be suffering from depression…

Depressive disorders, along with anxiety disorders, are the most common mental disorders in the world. In 2019, 280 million people were estimated to be suffering from depression, including over 10% of pregnant and postpartum individuals. The fact that depression today is so widespread points to a few explanations. Popular thought suggests that our modern lifestyles are influencing a rise in depression (or at least diagnoses), while others speculate that depression may have an evolutionary basis, which drives its persistence in populations. Theories that fast-paced, increasingly urban modern lifestyles are solely to blame are undermined by observations of depression in small-scale foraging communities, whose people have vastly different lifestyles to those of us in the West. Hence, an evolutionary hypothesis may be more plausible (although the theories are not necessarily mutually exclusive!). Perhaps because evolutionarily beneficial explanations for depression seem so counterintuitive, they have received little public and research attention. Despite this, a growing body of research proposes the possibility that depression confers an adaptive advantage. This has been termed ‘evolutionary framing’, and could redefine how we conceptualise depression, moving away from a model which treats depression as an abnormality to be eradicated, towards more empathetic understandings of it as an evolutionarily evolved response to the environment. But first, we need to understand why depression exists to begin with.

…suggests that depression refocuses resources away from normal activities in order to solve complex social problems.

There are multiple approaches to evolutionary explanations for depression. The first model, commonly referred to as ‘the dysregulation model’, suggests that certain mechanisms help us to survive and reproduce, so conferring an evolutionary benefit. Here, ‘dysregulation’ refers to the concept of mechanism malfunction, which may result in depression. For example, feelings of low self-esteem and rumination may trigger the decision to accept a low social status to avoid threatening those in power. While this feels unpleasant, it can increase one’s chances of survival. Alternative explanations suggest that the mechanisms causing depression are not dysregulated but functioning normally. This argument posits that depression itself is useful because it increases social support from others. This argument, often credited to Watson and Andrews’ social navigation hypothesis (SNH), suggests that depression refocuses resources away from normal activities in order to solve complex social problems. This has the secondary effect of signalling increased need for emotional investment and support from others. Here, it is necessary to caveat that this is a subconscious behavioural mechanism and does not mean to imply that people with depression deliberately exhibit attention-seeking behaviour, which is a pervasive and harmful misconception. In fact, an observation which weakens this argument is the common symptom of social withdrawal, which may contradict the supposed benefits of socialisation. Overall, both models are concerned with the evolutionary benefit created by the behavioural and psychological mechanisms responsible for depression but make different arguments about whether depression itself is adaptive or an unwelcome side-effect.

Some argue that depression itself does not have the characteristics of an adaptation. Unlike an adaptation, which increases the chances that an organism will survive and reproduce, depression often results in poorer social outcomes, higher mortality rates, and worsened physical health. Depression also differs from other psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia or anorexia; in a paper comparing the number of children (an important metric of evolutionary success) between patients with psychiatric conditions and their unaffected siblings, depression showed distinctly different patterns. Interestingly, siblings of depressed individuals tended to have more children than the broader population, perhaps suggesting that genes associated with depression are useful in certain circumstances. This supports the theory that, unlike schizophrenia or anorexia, there is likely no evolutionary force actively removing depression. Instead, depression may be maintained in the population through a process known as ‘balancing selection’, which selects for the average rather than an extreme tendency away from depression. Evolution may select for emotional regulatory mechanisms which facilitate the expression of a full range of emotions but activate before an individual’s health is seriously compromised. Due to circumstance and random chance, not all individuals will achieve a perfectly balanced optimum. Thus, evolution maintains low proportions of people with depression, but depression itself is not adaptive.

In light of this growing body of evolutionary research, it is doubly important to reflect on how evolutionary explanations may affect the individuals themselves who are suffering from depression. These interpretations of mental illness can be helpful by further clarifying to individuals that they are not “abnormal” or in need of “fixing”, but that their mental states are valid responses to their environment. For some patients, this may alleviate guilt and shame whilst normalising living with a psychiatric condition. On the other hand, suggesting that depression is adaptive could risk trivialising its pain or discouraging treatment. Subjective lived experience complicates the possibility of assigning one “scientific” (implication: “always true”) explanation for how or why depression occurs – everyone experiences and relates to their depression differently. Whilst some might perceive their condition as holding meaning, and may welcome evolutionary explanations, others may experience depression as purely debilitating, meaning that evolutionary frameworks provide little comfort. Greater research needs to be conducted to understand the social, cultural, and ethical implications of framing depression evolutionarily; this would avoid over-simplifying a serious and widespread illness into a “natural” state which doesn’t require medical intervention.

…everyone experiences and relates to their depression differently.

Evolutionary research on psychiatric illnesses is still in its infancy. Evolutionary perspectives cast new light on depression, complex as it is, as more than a set of symptoms, but an illness which must be treated and navigated at the root. Nevertheless, the jury is still out for whether evolution presents an appropriate explanation for depression at all. More than this, the possibility of an evolutionary function for depression does not negate that it causes immense distress for millions of people worldwide. Evolutionary explanations for behaviour are insufficient alone to fully understand this complex condition and may risk minimising systemic social factors such as socio-economic position or racial inequality, which have a key role to play in its development.

Evolutionary research should not be necessary to justify treating patients with empathy and respect.

Whether or not depression has an evolutionary background, it remains a debilitating condition. Evolutionary research should not be necessary to justify treating patients with empathy and respect.

**some ideas expressed in this article are opinion, and may not represent the opinion of The Oxford Scientist as a whole**