By Max Peacock, Year 13, Colyton Grammar School, Devon

In 2016 the world health organisation published a study into the global prevalence of type 1&2 diabetes. The study estimated that there are currently 422 million people living with some form of diabetes, over 100 million of whom are entirely dependent on insulin injections to live their day to day lives. The story of the discovery and manufacture of this incredible molecule follows the work of a brilliant young scientist whose single-minded perseverance and commitment to his craft has benefited the lives of millions of people worldwide.

In the late 19th century the prognosis for a diabetes patient was dire. Diabetics were resigned to a life of comatose weight loss and fatigue, and poorer families in particular could do little to help their ailing relatives. It was into this world that Frederick Banting was born, to a couple of Canadian farmers. Banting was an excellent sportsman but at school he flattered to deceive. His father was keen to push him towards the Methodist ministry. By all accounts, Banting was contented with taking this path, however in his latter school years his mind was profoundly changed. A classmate of Banting contracted diabetes and the future scientist watched in horror as his friend’s life sank into lethargy. The death of his classmate triggered a switch in Banting’s focus towards gaining a good medical education, and sparked an obsession that would stay with him throughout his professional career.

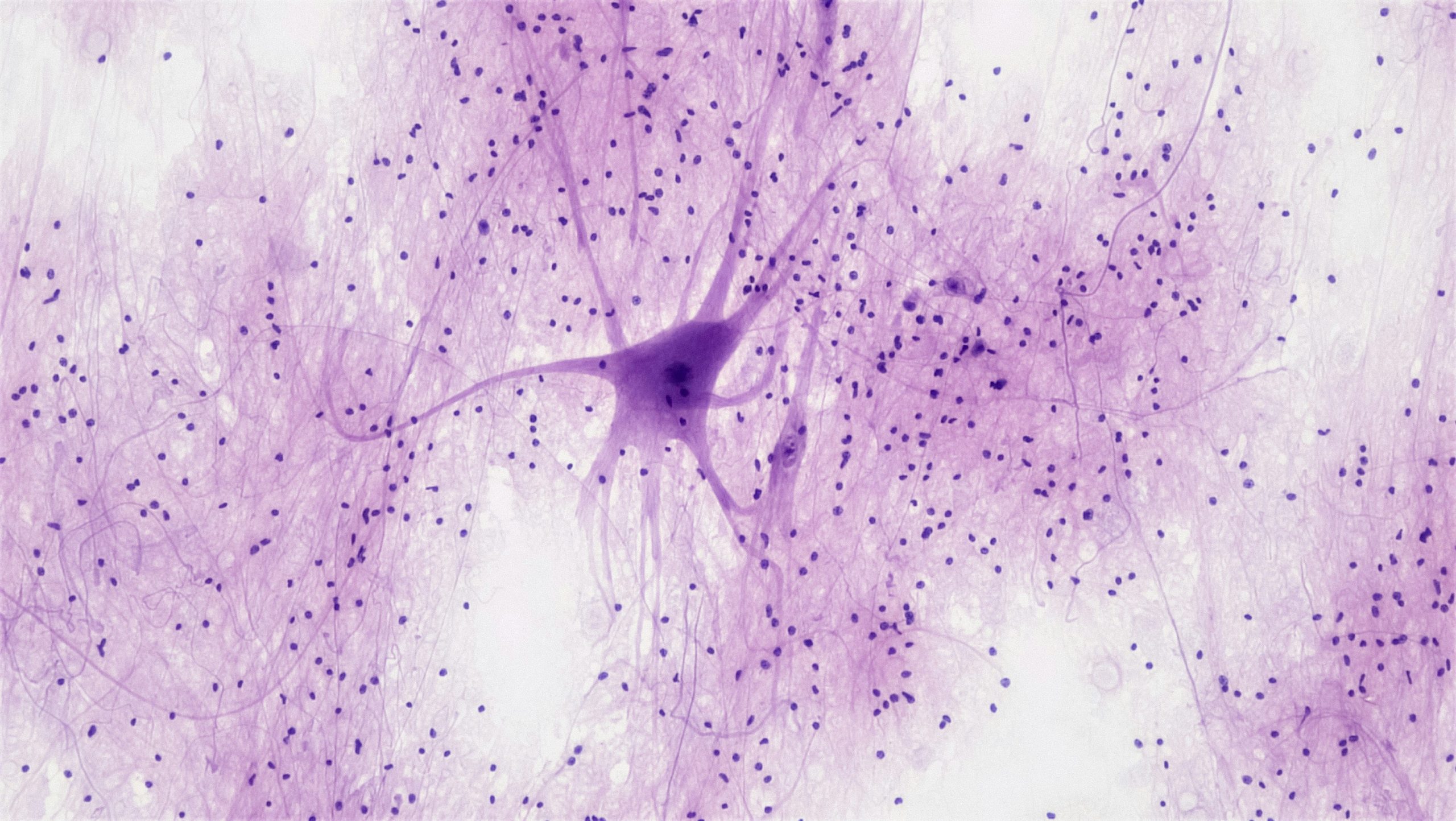

Banting’s father was initially opposed to the sudden change of heart, however it was eventually agreed that he would study both theology and medicine. In 1910 he enrolled at Toronto University. Banting’s stint as a theologian was short-lived: by 1912 he had dropped out of his religious studies to focus fully on his medical career. He developed a profound interest in haematology and came to focus his research on the ‘Islands of Langerhans’, particularly their secretion of the mysterious ‘hormone X’.

Like so many of his generation, Banting’s career ground to a halt in 1914 and he gave up his laboratory for the trenches of Cambrai. The young Canadian sustained a serious shrapnel wound but despite his injuries he continued to work to rescue his stricken comrades. For his bravery Captain Banting was awarded the Military Cross, and he would return to his work with a wealth of new surgical experience.

On his return to Canada, the young doctor began a placement at the Toronto children’s hospital and his focus seemed to shift towards orthopaedics and surgery however in November 1920, Banting stumbled across an article that professed a link between hormone X and the management of diabetes. Lying in his bed at night, Banting had an epiphany, and he hurriedly noted down his thoughts: “Ligate pancreatic ducts of dogs, wait for degeneration,”

Banting’s breakthrough led to the first refinement of hormone X, as ligating the pancreas left the Islets of Langerhans cells intact. On July 30th 1921, Banting tested his hormone therapy on a terrier. His assistant recorded a lowering of the subject’s blood glucose. The treatment had worked! Well… nearly. The dog died the next day and Banting was forced to experiment with different dosages. The Islets of Langerhans cells are more prevalent in younger animals, and Banting was aware of the surplus of embryos at an animal slaughter house. He reasoned that the embryos would be even richer in the pancreatic cells and so could provide a commercially viable source of insulin.

Banting’s vision for the future of diabetes had come to fruition. In 1923 became the youngest Nobel Prize winner for medicine, an achievement he still holds to this day.

Despite the fame and prestige that befell the young scientist, Banting remained profoundly humble. His pursuit of insulin stemmed from a genuine infatuation in human physiology and his dedication and self-belief allowed him to succeed despite the dismissal of more senior physicians. His love of science was unwavering and his passion for learning is an inspiration to any young scientist. Always a student, a 37-year-old Banting once remarked: “It is not within the power of the properly constructed human brain to be satisfied; progress would cease if this was the case.”