Novel research into the neurotransmitter acetylcholine may drive a new era of antipsychotic drug development. Photo credit: Massimiliano Sarno via Unsplash

For decades, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders have been seen through the lens of dysfunctions in dopamine, an important neurotransmitter (chemical messenger) in the brain. This is reflected in the main treatments of schizophrenia, which have all targeted dopamine signaling since the first antipsychotic was developed in 1951. While these drugs effectively reduce perception-altering, “positive” symptoms like hallucinations and delusions, they fall short in treating “cognitive” symptoms such as memory and thinking difficulties, and “negative” symptoms like social withdrawal and lack of motivation. Additionally, the side effects of these drugs, including movement disorders and weight gain, significantly impact patients’ quality of life.

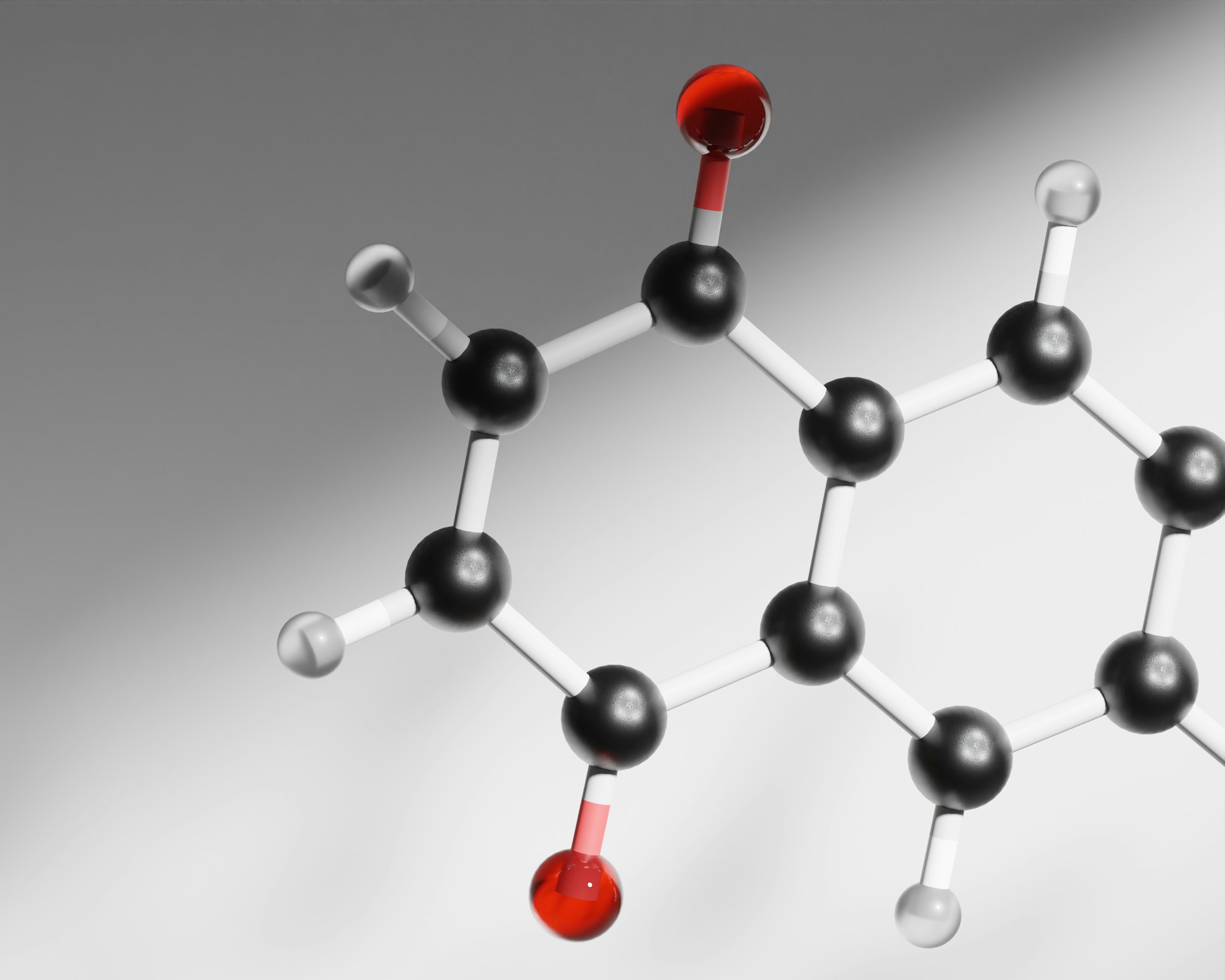

However, recent research has brought a new neurotransmitter into focus: acetylcholine. Acetylcholine plays an important role in many aspects of cognition, like attention and memory. One promising drug—xanomeline —targets this system and has emerged as a potential treatment for a range of symptoms of schizophrenia. It activates one of the receptor types of acetylcholine in the brain: muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Interestingly, it had been considered for use in schizophrenia in the 2000s, but was somewhat forgotten due to nausea and many dropouts in clinical trials. However, the simple but intelligent addition of a drug, tropsium chloride, that blocks its nausea-inducing peripheral effects has allowed for proper investigation of its potential as a treatment.

It became the first-ever antipsychotic with a non-dopaminergic mechanism of action.

Following positive outcomes in clinical trials, the FDA approved this drug in September 2024 under the brand name Cobenfy. It became the first-ever antipsychotic with a non-dopaminergic mechanism of action. This historical approval marked a shift in our understanding and the future of psychosis treatment. While not yet approved in the UK, the University of Oxford is set to launch the first UK trial later this year, as announced by Dr. Robert McCutcheon. If the results of this trial are positive, it could pave the way for the drug’s use by hundreds of thousands of individuals living with schizophrenia in the UK.

This is very exciting as acetylcholine-based treatments appear to alleviate both positive symptoms and cognitive symptoms, which traditional antipsychotics don’t treat. Its treatment of cognitive symptoms makes sense with the wealth of literature implicating acetylcholine as an essential neurotransmitter in cognitive function. Early data also suggests that these new drugs are better tolerated than dopaminergic treatments, offering hope for improved quality of life for patients.

…frequently prescribed medications could be leading to increased cognitive decline in patients.

The new focus on acetylcholine has also prompted researchers to reevaluate existing treatments. A recent meta-analysis from Oxford University examined the use of anticholinergic drugs, which are often prescribed to manage the movement disorders caused by traditional antipsychotics. The study found a negative correlation between anticholinergic activity and both global cognitive performance and specific elements of cognition like learning and memory functions. This highlights how frequently prescribed medications could be leading to increased cognitive decline in patients. First author on the paper, Dr Mancini, said, ‘From a clinical perspective, tapering off anticholinergic medication could be beneficial for their cognition, but further research is needed to prove this without question’.

…this new direction could unlock therapies that target the full spectrum of symptoms in schizophrenia…without the burden of debilitating side effects.

Thus, this paradigm shift is not only driving a new wave of antipsychotic drug development, but also prompting a reevaluation of how we treat psychosis. Scientists are hopeful that this new direction could unlock therapies that target the full spectrum of symptoms in schizophrenia—positive, negative, and cognitive—without the burden of debilitating side effects. There is also growing excitement about the potential for anticholinergic drugs beyond psychosis, with Dr McCutcheon noting that ‘cognitive enhancers have transdiagnostic potential’ and that ‘there is significant interest in cholinergic drugs as both antipsychotics and cognitive enhancers’.

As the first UK trial is set to start this year, the scientific community is watching closely. Many are wondering: could this be the dawn of a new era in psychosis treatment?