Rania Ocho, Year 12, St Philomena’s Catholic High School for Girls

When I say doctor, what do you envision? Draping white coats and blue scrubs accompanied nicely with a stethoscope, I imagine. Scopes that wrap around their necks, almost like rings to a marriage – but for a doctor, it signifies their endearing commitment to helping others. But this modish instrument did not dangle around a doctor’s neck till about two centuries ago, founded in 1816 by none other than René Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec, a French musician, and physician. Laënnec, the man whose wit, inventiveness and embarrassment, led him to discover the hallmark of any doctor; the father of clinical auscultation.

Imagine a scenario set in early Greece. You’ve been haunted by a sickly cough, fever, and some shortness of breath. Confiding with Hippocrates himself, he grabs your shoulders, places his ear directly to your chest, and begins to vigorously shake you, inducing sounds from your thorax. Immediate auscultation, a diagnostic procedure where the patient will experience what it’s like to be a ragdoll for a few minutes.

Surprisingly, not much changed from this approach until the 18th century. Alike to most great things, wine was a major cofactor. Josef Leopold Auenbrugger, an Austrian physician, was the son of an innkeeper. He would frequently hear his father check whether the barrels of wine were full or not. His father would hit the barrels expecting duller noises from those that were wine-filled, and lighter noises from those nearly empty. Auenbrugger realised the similarities between the lungs and wine barrels. Thus, diagnostic percussion was birthed, and with these findings, we are brought to 1816 René Laënnec.

One September morning, in 1816, René Laënnec was strolling through the courtyard of Le Louvre Palace in Paris till his walk was interrupted by two children playing with a solid plank of wood. Curious, Laënnec watched them use this wooden plank to send sound signals between themselves. This was done by one end being scratched by a pin sending a signal to the other. Of all of our weird curiosities in life, some would resurface again as a fond memory or be of greater significance. For Laënnec, it was the latter.

Later that same year, Laënnec would be visited by a woman who had the general symptoms of a diseased heart. However, with the patient being a young and developing woman, naturally, Laënnec was hesitant to perform immediate auscultation. Head in hand, an embarrassed Laënnec, desperately searched to find a resolve; to what seemed like his demise, he suddenly remembered the children at the Louvre. Laënnec then reached for some papers and tightly rolled them placing one end at his ear and another at the woman’s precordium. To his surprise, Laënnec heard the heartbeat with significant clarity – such clarity where not only the heart but other sounds in the thorax could be heard. A diagnostic breakthrough. Laënnec’s mediate auscultation.

Laënnec knew this discovery was monumental, so for the next three years, he dedicated time and effort to materialising his finding and used patients with pneumonia to help determine what material was best. Followed by various other scientists such as Rappaport, Sprauge, and Groom, adjustments were tweaked and features were added until the present day stethoscope was made.

Laënnec helped shape a new diagnostic approach of internal bodily examination through auscultation, which up until this point, was unheard of (unless you were discussing autopsies, but by then, the patient was long gone). Laënnec’s discovery was humble, deferential, and truly quite creative. Resourceful, and mindful…the list is endless. But the definitive point that can be made, was Laënnec’s desire to help someone, and how it transgressed past his textbook knowledge and required a more creative outlook.

Ultimately, I believe every scientist has a creative wick burning within them, and like Laënnec, carries a legacy of change – regardless of scale and recognition. Laënnec’s creative compassion was truly inspirational and something we can all hinge on. The science of the future will depend on our creative outlook in life and how we can apply them. With Laënnec’s story, and others alike, I have the utmost confidence that the future of science will be something quite extraordinary and possibly breathtaking. But not to worry, we’ll use stethoscopes to check that.

Runner-up for the Schools Science Writing Competition, Hilary Term, 2021

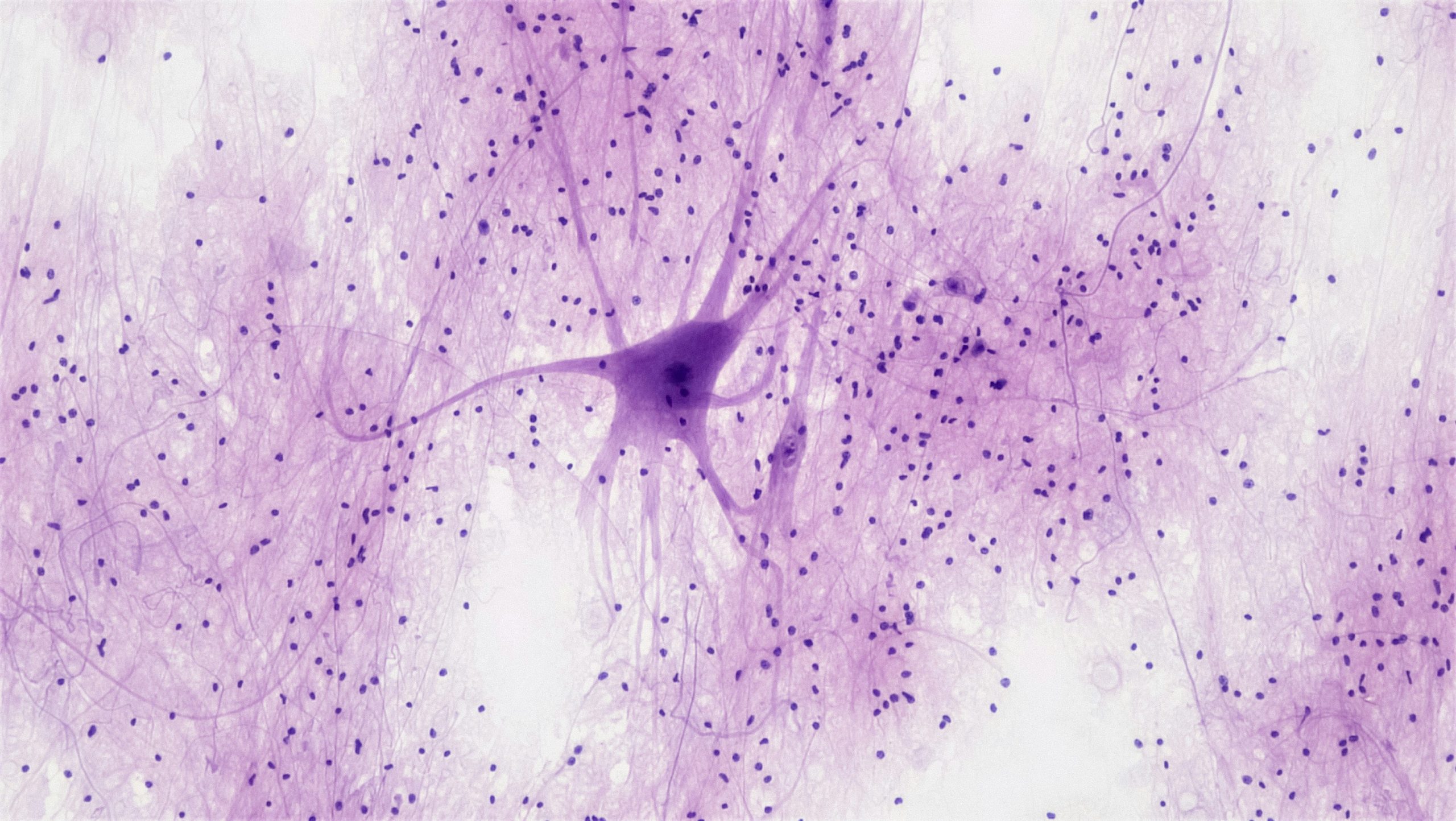

Image credit: Roger Brown via Pexels