Lecanemab, a new drug for Alzheimer’s, offers hope for those in the early stage of the disease. Photo credit: Philippe Leone on Unsplash

In August, a new drug by the name of Lecanemab, that has been shown to reduce the rate of progression of Alzheimer’s disease, was licensed for use by adult patients in the UK. It shows great promise for the future of treatment in this field but is not yet offered on the NHS.

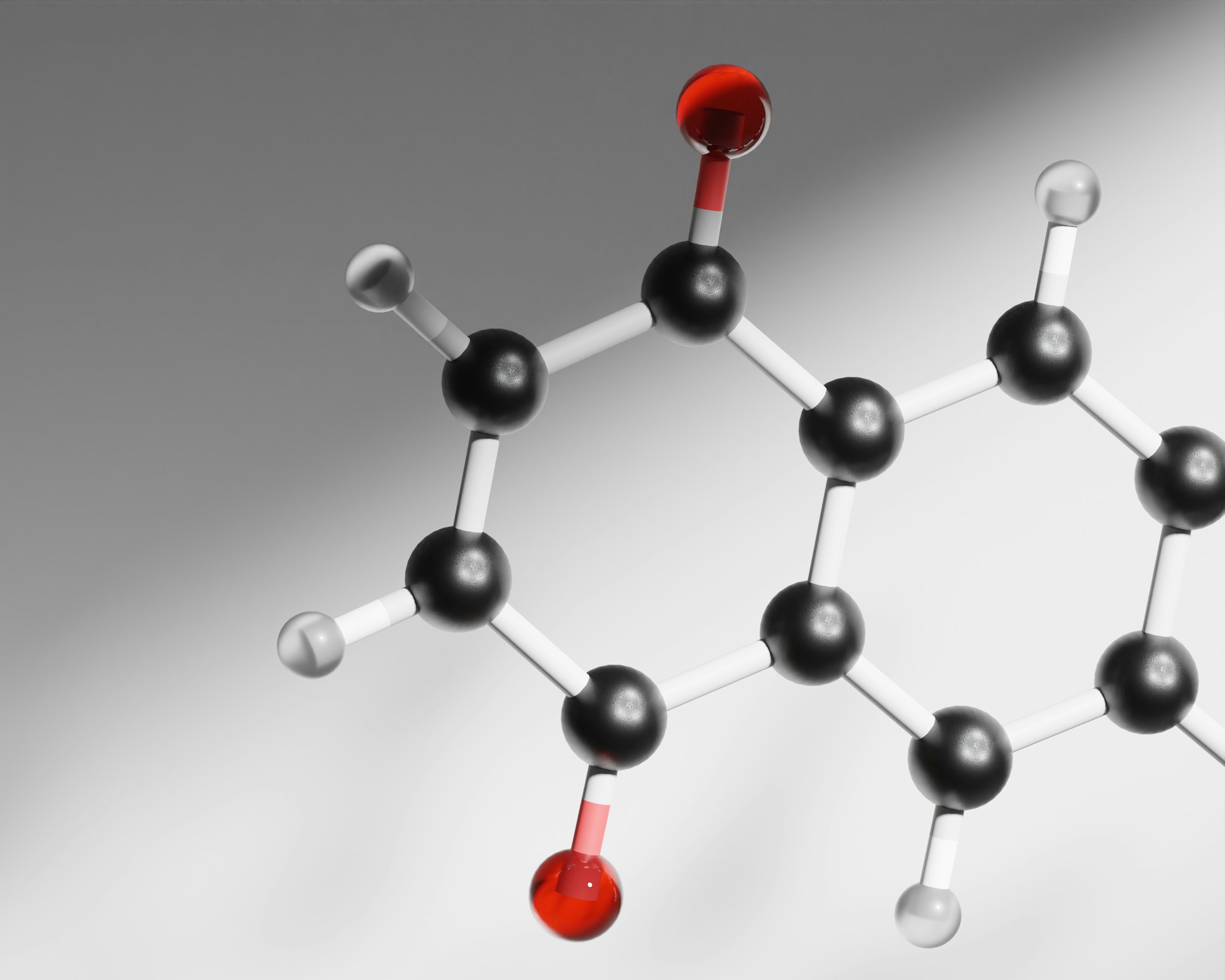

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease most prevalent in people over the age of 65. It is characterised by three main changes in the biology of the neurons in the brain: a reduction in the quality of the neurons, the formation of ‘tangles’ of a protein called tau, and the formation of ‘plaques’ of a protein called amyloid-beta. It is this amyloid-beta in particular that draws a lot of focus as a potential therapeutic target.

…aggregation of amyloid-beta protein into plaques between the neurons in the brain results in rupturing of the cell membranes and, eventually, cell death.

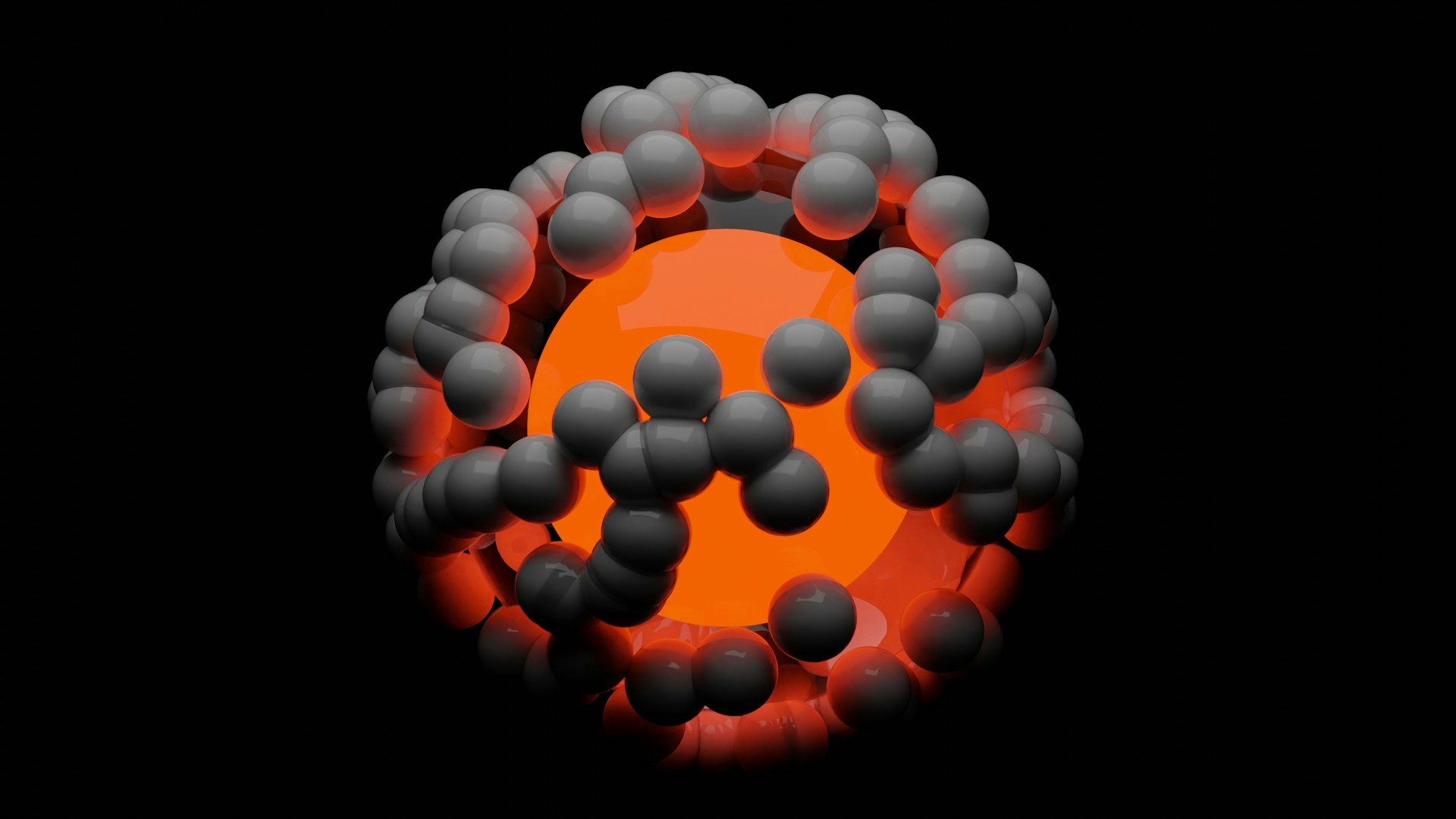

The ‘amyloid hypothesis’ regarding the cause of Alzheimer’s suggests that the aggregation of amyloid-beta protein into plaques between the neurons in the brain results in rupturing of the cell membranes and, eventually, cell death. The Lecanemab drug is a monoclonal antibody which binds to the amyloid-beta molecules in order to fight this. Antibodies are small molecules that bind to a foreign body and trigger the immune system to destroy it. This drug causes the amyloid plaques to be broken down by the immune system, slowing the rate of neuron damage.

This drug causes the amyloid plaques to be broken down by the immune system…

The drug was proven effective in an 18 month clinical trial which recruited individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s between the ages of 50 and 90, with a total of 1795 participants enrolled. The effects of the drug were quantified by measuring patients’ cognitive ability on the Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) scale, where a score closer to the maximum of 18 indicates greater impairment. Before the trial began, the starting baseline CDR-SB score was approximately 3.2 for both groups (placebo and Lecanemab). After 18 months, the change from baseline was 1.21 for those treated with Lecanemab compared to 1.66 in those given placebo. Therefore, those treated with Lecanemab had 0.45 points less decline in cognitive function, meaning the rate of decline slowed by a quarter over the 18 months.

According to Dr Elizabeth Coulthard of the North Bristol NHS Trust, this slowing in decline would equate to around 19 extra months of independent living. This sets Lecanemab apart from most other Alzheimer’s drugs which can only treat the symptoms, rather than altering the underlying progression of the disease. As such, this drug is without a doubt a momentous breakthrough in the field of Alzheimer’s treatment. In fact, Lecanemab exceeded the estimated 0.373 CDR-SB point decline that was predicted beforehand.

…this slowing in decline would equate to around 19 extra months of independent living.

Nevertheless, it is not yet defined what change in score on the CDR-SB scale would indicate a meaningful result, and the drug is yet to be trialled over a more extended period of time so its longer-term efficacy is not yet recorded. Furthermore, like with any drug, there are side effects: 17% of the Lecanemab group experienced brain bleeds and 13% experienced brain swelling. These side effects resulted in 7% of the Lecanemab group discontinuing use of the drug part way through the trial.

…this drug cannot slow the effects of all types of dementia.

It should also be noted that this drug cannot slow the effects of all types of dementia. There are an estimated 982,000 individuals in the UK with dementia of some sort, over half of those being Alzheimer’s. The remainder of the cases include conditions such as vascular dementia (caused by reduced blood flow to the brain) or dementia with Lewy bodies (accumulation of alpha synuclein protein). Lecanemab cannot treat all of these conditions, since it is specific to the amyloid-beta protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, in Alzheimer’s disease, other proteins such as tau also cause damage and contribute to cognitive decline, but these are not specifically targeted by Lecanemab. This being said a substudy did show that markers of both amyloid-beta and tau were reduced more by Lecanemab than by placebo.

Another pressing issue associated with Lecanemab is the timeline of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. This drug is only effective in treating those with early-stage Alzheimer’s as the regulatory body MHRA has deemed it unsuitable for individuals with mid or late-stage Alzheimer’s due to a higher risk of side effects. Therefore, it requires a patient to be diagnosed early, which often does not happen.

This drug is only effective in treating those with early-stage Alzheimer’s…

The Alzheimer’s society has found that one in four people struggling with dementia-like symptoms wait two years before they will seek medical help, and by the time many patients get a diagnosis, it has progressed past early stage and therefore they are no longer eligible for this treatment. Once a dementia diagnosis is made, the patient must then be tested for amyloid-beta related Alzheimer’s using a Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan or a cerebrospinal test, which currently only around 1–2% of dementia patients undergo. As a result, Lecanemab cannot begin to tackle the problem of treating Alzheimer’s without a revolution in the early diagnosis of the disease.

Currently the drug is licenced for use in the UK, but it is not being offered on the NHS, with the healthcare assessment body NICE stating the benefits ‘are too small to justify the cost’. The treatment is available privately though and, while a cost in the UK has not been announced yet, the cost in the US reaches the equivalent of around £20,000 per patient per year.

Today’s society is an increasingly ageing population and hence the prevalence of neurodegenerative disease is growing rapidly. Kate Lee, chief executive of Alzheimer’s Society, names dementia as the ‘biggest health crisis we face in the UK’ with Alzheimer’s and other dementias being the leading cause of death in England and Wales in 2023. The number of people globally with Alzheimer’s currently reaches 55 million and is expected to rise to 139 million by 2050. The need to treat this disease is an urgent one– and this breakthrough with Lecanemab is most certainly a step in the right direction. is most certainly a step in the right direction.