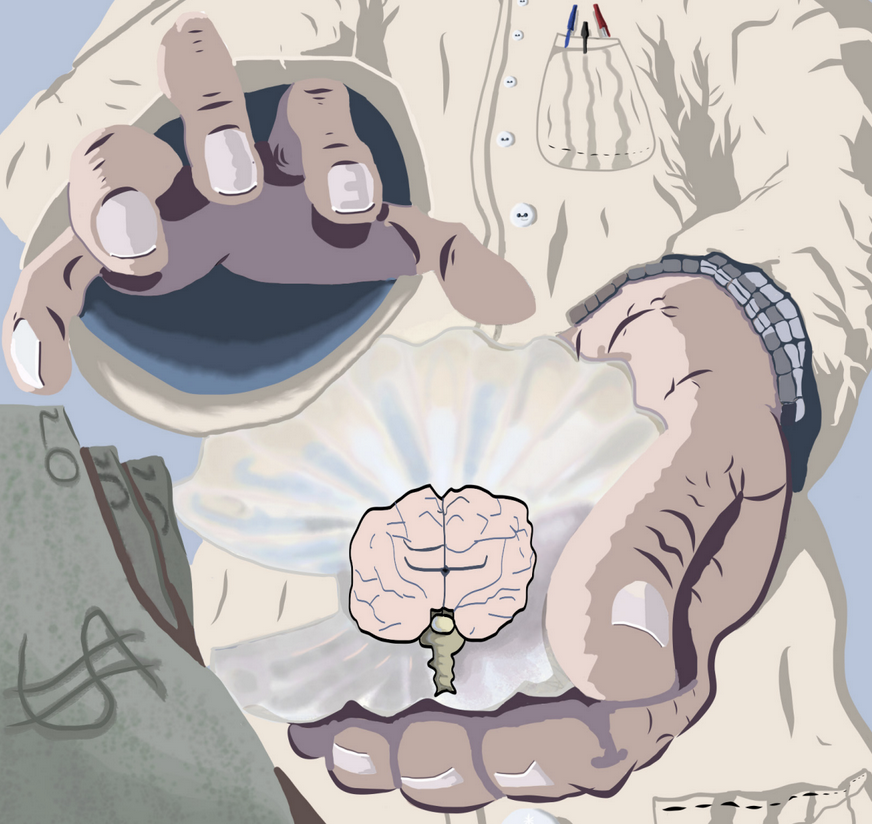

Artwork from the Print edition by Daniel Coneyworth.

This article was originally published in the Oxford Scientist’s Print edition, Barriers, in Michaelmas Term 2022. You can read more of our Print articles here.

Intellectual property, or IP, refers to the lawful protection of ideas, inventions, and discoveries of apparent commercial value. With a rich history which dates back over 2000 years to when chefs in Ancient Greece would protect the recipes of their culinary delights, IP has long served to safeguard a creator’s right to exert control over, and reap benefit from, the fruits of their labour. In the present day, IP can adopt different forms depending on the assets in question, with each having its own unique set of regulations and processes.

For example, patents—perhaps one of the most well-known manifestations of IP—are written documents which describe and protect novel inventions; copyrights (©) serve to protect art and computational software; and trademarks (TM or ®) are used to register a monopoly over branding that denotes the provenance and perceived quality of an item or service. Collectively, these IP rights, enshrined by legislation, defend against the piracy of original work. As such, in the present climate of innovation and development, they serve to reward our ideas… “You wouldn’t steal a car!”

Despite the myriad benefits of intellectual property, exerting formal rights over our creations may have certain downfalls. For instance, registering and maintaining valid IP licences comes at considerable monetary costs in the form of lawyers and court fees. In addition, IP does not offer infallible means of protection, and is limited in scope by both territoriality (protection is restricted to countries in which IP has been granted) and lifespan (protection is restricted to a finite period, typically 20 years in the case of a patent). Finally, and arguably most importantly, IP generally obliges public disclosure of technical information relating to the innovation at hand. Therefore, gaining IP protection is costly, and could inadvertently advantage otherwise ignorant future or international competitors to your secret recipe for success.

Further, owing to stringent requirement standards of originality, non-obviousness, and practical utility, not all ideas are able to privilege from formal IP rights. As such, when the benefits of the above-described IP methods are not considered to outweigh the risks, an alternate strategy for commercial protection can be enacted as one of complete non-disclosure: trade secrets. Some of the most famous business assets have remained well-guarded using this practice, including Coca-Cola’s formula of their signature fizzy drink, as well as Colonel Sanders’ 11 herbs and spices in KFC fried chicken. Yet, trade secrets are not a golden bullet of protection and suffer their own Achilles’ heel in the form of enforcement difficulties. Regardless of the means employed for commercial protection, whether in plain sight or behind the door of a secure bank vault, it is evident that IP impinges upon every facet of the world we live in.

Although the importance of intellectual property to the development of our society has been unequivocal, the application of these exclusivity rights in the life sciences has spurred controversy. Since the declaration of the first biological patent in the USA in 1903 over the purified compound adrenaline, the commercialisation of the natural world has been the source of hotly debated social and ethical issues. Staunch critics of biological IP point toward moral concerns surrounding ownership of biological material, as well as perceived threats to our health and the environment. Other complex issues have also arisen such as profiteering from religious violations to the sanctity of life, and the commercial exploitation of indigenous knowledge in what is heralded as “scientific colonialism”.

Nonetheless, advocates of biological IP contend that like any area of innovation, protective ownership of ideas is what enables their work to have maximal benefit to the public. In essence, they argue that IP frees science from the plastic test tubes in a laboratory allowing it to have a significant impact in the real world. The harsh reality is that money drives society, and thus if science is not commerciable, it has no seat at the international conference of our planet. That is, of course, without the exception of such a seat being propped up by not-for-profit organisations or philanthropic billionaires. Though this would only be a temporary fix, as no pocket is infinitely deep, and no amount of good-will is boundless.

With tensions surrounding intellectual property in the life sciences continuing to rage with modern advances in genetic engineering, it is clear that this topic is more relevant than ever. Like it or not, the practice of IP in biology is widely accepted and here to stay. Therefore, this debate must focus on adequate and transparent regulation, rather than presence or absence. IP in the biological sciences is what continues to champion our technological development and progress as a knowledge-driven society. By incentivising innovation, researchers are ultimately motivated to tackle the grand challenges we currently face, including climate change, food security and global health. Crucially, IP has the potential to shape the industries and opportunities of our future.