Exploring the intersection of public trust and scientific discovery during the COVID-19 era. Image credit: Charles De Luvio, via Unsplash.

Mariam Elalfy, a student at Wolverhampton Girls High School, is the Year 10-11 winner of the 2023 Schools Science Writing Competition. You can read more about the winners and runners-up here.

From Galen and Hippocrates to modern-day prodigies, humanity has continually relied upon professionals providing us with advice we utilise daily. This ranges from brushing our teeth for two minutes bi-daily to avoiding breakfast to improve metabolism. Health, however, is a unique specialist area- in a sense that everyone feels autonomy over their own body; thus, if you ‘feel’ something works better for you (be it placebo or true effect) you might argue if there’s any reason to follow expert advice at all.

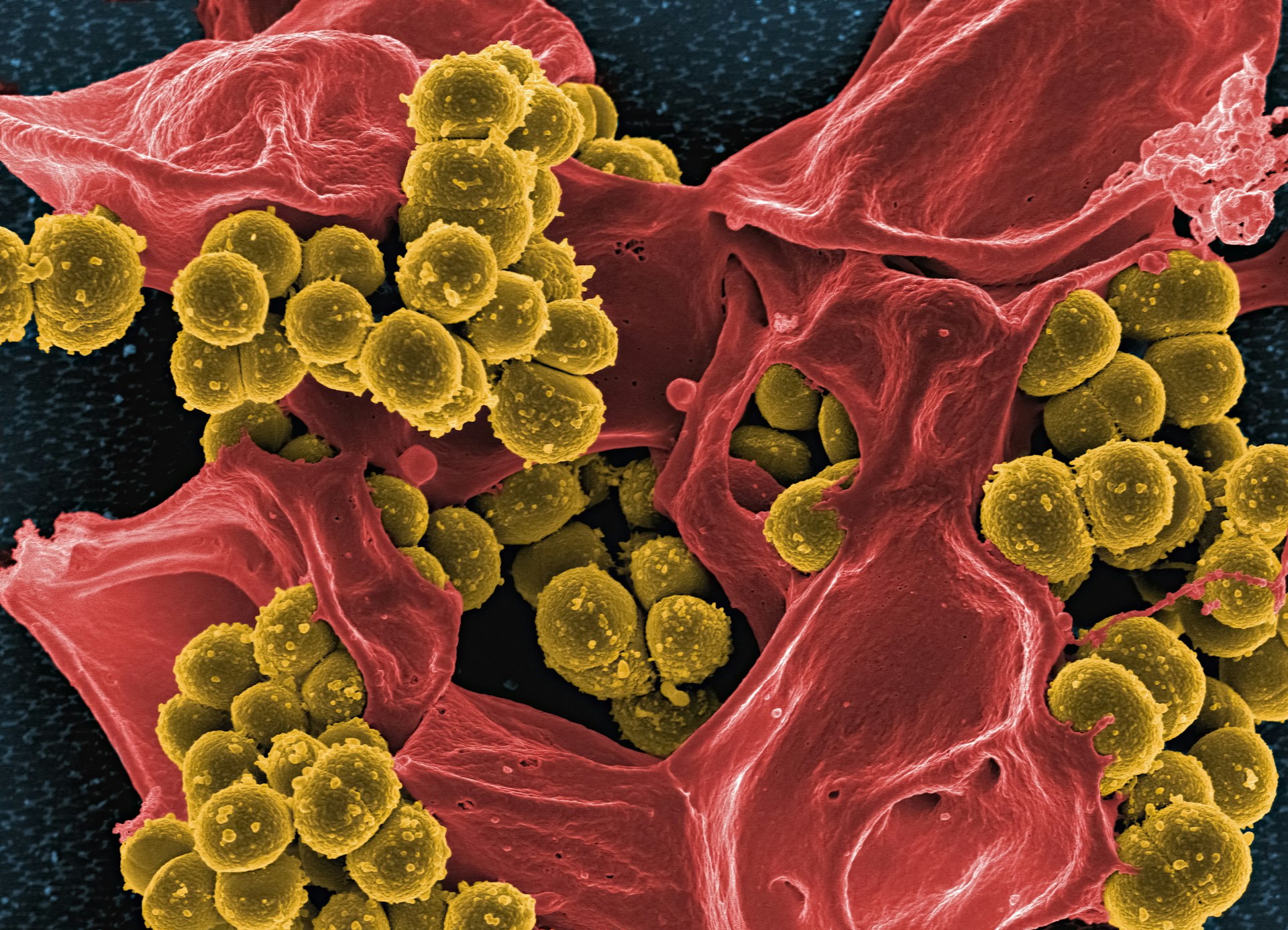

When the pandemic hit, people paid more attention to the news than ever before. How does it spread? What are the symptoms? Who is most at risk? Scientists were being watched under a microscope. These questions concerned the public making them apprehensive and distressed; the people wanted immediate answers- oftentimes before evidence bases could support or rule out answers. Undeniably, the experience of COVID-19 reinforces the need to address public access to good quality research, with misinformation rife online. It underpins the importance to seek knowledge and close the gaps between the scientific consensus and public understanding. COVID-19 has unveiled a growing challenge in dealing with disinformation which can be led astray by deceptive directed content. As medical understanding evolved and advice changed over time, findings were subject to detailed scrutiny meaning initial conclusions were often modified. These scientists were driven by urgency and relied on public willingness to adapt. Turbulence in the media world meant the journalistic communication of accurate science to the public became quintessential to trusting science.

Academic communication allowed unprecedented speed and volume of discovery over the past year, with researchers unravelling molecular details of the virus, understanding the escalation, and discovering completely new ways of creating vaccines-namely mRNA- to tackle it.

When public trust is fragile, any uncertainty erodes their confidence, thus careful communication is paramount in supporting policy implementation.

Nonetheless, these changes were not accepted by all; a study in 2020 found Indonesians show equal trust in their scientists as their traditional healers. Take the shifting guidance on face masks- initially policies warned against them in fear of inadequate supplies. Then scientists learned more about airborne transmission of COVID, urging people to wear masks. Therefore, we struggled to apprehend science is not a textbook construction, rather a process of lateral thinking carried out continually. When public trust is fragile, any uncertainty erodes their confidence, thus careful communication is paramount in supporting policy implementation.

Vaccine-related issues dominated the perception of science’s impact on COVID-19. In a recent study, vaccine acceptance was significantly higher among younger (<32 years) participants and among those with more education ( >high school). This becomes further convoluted due to political devotion. For example, science proves facemasks as effective in preventing infection, yet many confront wearing them (or not) as taking a political stance rather than a matter of public health. It became a battle, scientists vs politicians; people felt obliged to display their bureaucratic loyalty and scientific ignorance.

Meanwhile Vietnam thrived, using full lockdowns and mask-wearing mandates, proving unequivocally how essential science was during this process and public interest in hearing directly about the research conducted by scientists jumped by nineteen percent (63% to 82%). In Germany (2019) 46% indicated they trusted science but in April 2020 this rose to 73%. The danger of not accepting scientific advice is seen when ethnic minorities and elderly people were refusing the vaccine when these were the people most at risk of complications due to the virus. This hesitancy must be examined in a multifaceted, socio-cognitive context as it challenges the healthcare system and healthcare workers.

From the creation of the universe to the shape of the world we live on, science will never convince us all; maybe covid has changed our perspective?

Standards for science changed and perhaps vaccines and medicines can be developed in mere months in the future. In underlying terms, faith in scientific credibility becomes sustainable by making research transparent. Thus, this appears to be an opportunity for crucial structural reforms to make investigations universal. As public trust increased, covid-19 provided an opportunity for accelerating developments for pragmatic change.

From the creation of the universe to the shape of the world we live on, science will never convince us all; maybe covid has changed our perspective? It may have inspired conspiracies, fear and rage but it ignited something far greater- a renaissance-like passion in the people to discover truth for themselves.