http://www.scientificanimations.com, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Owing to a pioneering drug deal and a concerted effort to find people at risk, the NHS is set to eliminate hepatitis C by 2025, five years before a global target.

Health officials from NHS England have released a report detailing recent progress towards eliminating hepatitis C. This comes after the NHS was awarded almost £1bn in a five-year contract to fund antiviral drugs for thousands of patients in 2018.

Deaths from complications of hepatitis C including cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer have fallen by 35% in England since 2015. This exceeds the World Health Organisation (WHO) target of a 10% reduction by more than three-fold.

In addition, England has already met the WHO 2030 interim target of achieving a hepatitis C related mortality rate below 2 per 100,000. If this progress continues, England could be the first country in the world to have eliminated hepatitis C as a public health risk.

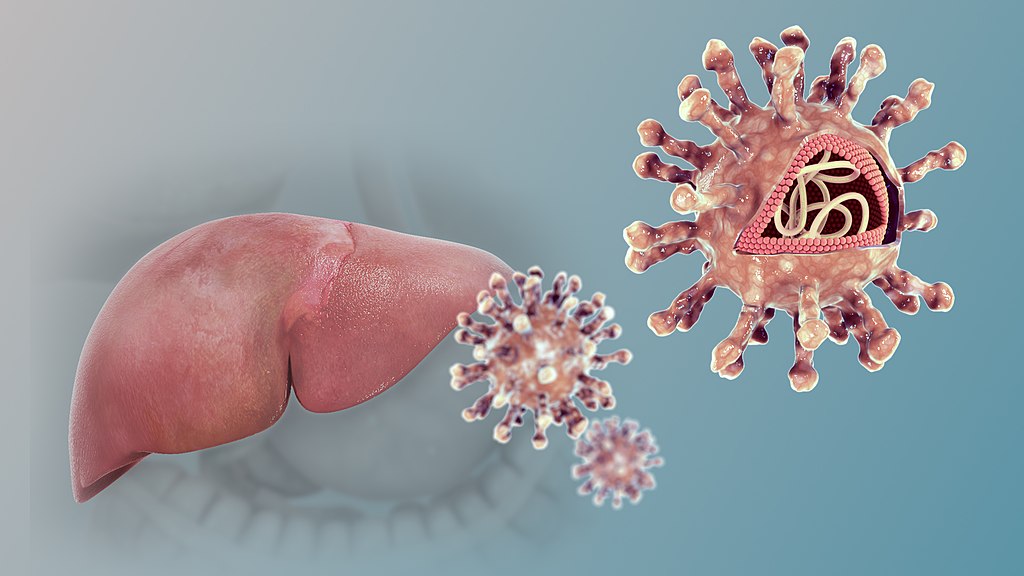

Hepatitis C is a blood borne virus that can lead to chronic liver inflammation and liver damage if left untreated. Historically, hepatitis C has been a challenging public health issue to manage, as new infections are often asymptomatic, leaving some infected individuals unaware of their diagnosis until serious liver complications arise, often decades later.

In addition, as hepatitis C is transmitted through blood-to-blood contact, the most “at-risk” demographics are also some of the most marginalised in society, including people who inject drugs (PWID) and men who have sex with men (MSM).

Misinformation has led to a vicious disease-based stigma at both an individual and population level, discouraging people from getting tested and treated if they suspect they may have been exposed to the virus. A 2020 study found that 95.5% of patients with hepatitis C had experienced some degree of perceived disease-related stigma from others. Often PWID have also experienced homelessness, worsening health outcomes due to difficulties accessing appropriate health services.

The tremendous success of the NHS in building and implementing an effective strategy to tackle the hepatitis C crisis in light of these challenges cannot be understated. The strategy has had to be multifaceted. While there’s no debate that the 2018 funding for curative antiviral drugs such as the combination therapy Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir has been paramount to the reduction in Hepatitis C deaths in England, community-based screening and outreach programs have been equally important.

Dedicated NHS “Find and Treat” programmes, delivered in partnership with local charities such as St. Mungo’s in Oxford have been successful in driving down cases of hepatitis C amongst vulnerable communities.

The Oxford team is one of many working to provide same-day screenings for those who have been previously hard to reach and treat. In addition to blood tests for hepatitis C, specially equipped trucks visiting at-risk communities can also carry out on-the-spot liver fibrosis scans to detect liver damage immediately.

Sara Hide, a hepatitis C co-ordinator at St. Mungo’s told NHS England: ‘With treatment for hepatitis C now less invasive—a course of medication for 8–12 weeks—we’ve seen an uptake in people responding to our screening services. We also screen for other conditions at the same time to identify clients that might need extra health support.’

Community vans and specialist teams across the country are also visiting drug and alcohol services, probation services and prisons, places of worship and community clinics and support groups. This allows people to get quick and convenient testing close to home, which is particularly important for at-risk people who may find it difficult to travel long distances to hospital-based services.

This is a promising step forward in reducing health inequality in the UK. Indeed, more than 100 children have also received infection-curing antivirals in the last year. These children come from some of the UK’s most deprived areas, with hundreds more expected to benefit in the coming months as part of the NHS Long Term Plan.

To boost progress towards eliminating hepatitis C, the NHS has also launched new technology which searches health records for key hepatitis C risk factors. Examples of these factors include a HIV-positive status or blood transfusions given pre-1992. Prior to 1992, donated blood was not screened for hepatitis C in the UK, and often came from ‘risky’ sources, such as the US prison population.

This technology, established in September 2022, could allow ‘up to 80,000 people unknowingly living with hepatitis C to get life-saving diagnosis and treatment sooner‘ according to NHS England. Those identified as being at-risk of hepatitis C according to the Patient Search Identification (PSI) software will be invited for review by their GP, and if appropriate, for further screening and treatment.

Rachel Halford, chief executive of the Hepatitis C Trust, described the new primary care screening technology as a ‘crucial step towards achieving elimination.’

The progress towards the elimination of hepatitis C is a tremendous success for the NHS, tackling what was a historically difficult public health issue to manage. Effective antiviral drugs can now cure over 95% of those who contract hepatitis C, with minimal side effects.

As the NHS continues to improve public awareness of hepatitis C, reduce stigma, and encourage those who may be at risk to get tested, England is on course to be the first country to eliminate the virus as a public health risk.