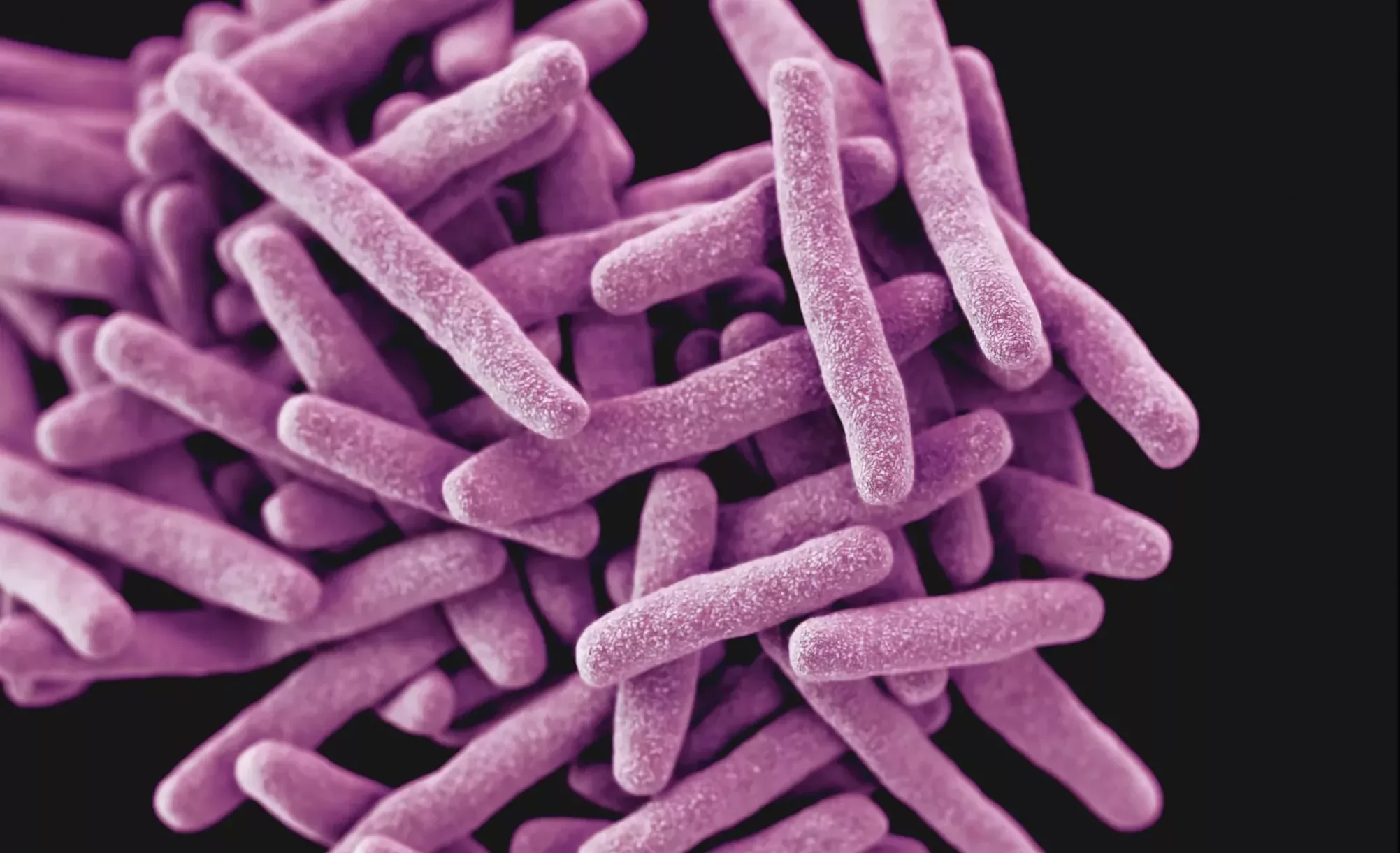

Bacterial infection could be responsible for endometriosis. Image credit: CDC, via Unsplash.

The 14th of June 2023 marked the release of a paper suggesting endometriosis is linked to an increased population Fusobacteria in the human gut microbiome. Endometriosis is a long-term condition affecting over 1 in 10 women of reproductive age where tissue akin to the lining of the womb grows in regions of the body such as the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Patients experience significant pain, particularly in the lower stomach and back area, as well as bloating and excess menstrual bleeding. The condition is associated with reduced fertility and individuals have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. We currently have limited treatments which include painkillers and hormonal medication and do not have a good understanding of what causes the condition.

Currently, retrograde menstruation is the widely accepted cause of endometriosis. The theory proposes that endometriosis occurs from retrograde flow of endometrial cells and debris via the fallopian tubes during menstruation. Though this occurs in 76-90% of women and not all of them go on to develop endometriosis. Further studies in the area are required to better understand the cause and therefore develop more effective treatments. The study published earlier this month on 155 women from Nagoya University in Japan found the bacterial genus Fusobacterium in the uteruses of 64% of those with endometriosis and 7% of those without the condition. Additional experiments in the paper showed that antibiotic treatment in mice infected with Fusobacterium could reduce the size and frequency of the lesions associated with endometriosis.

We currently do not have a good understanding of what causes endometriosis.

Fusobacterium is an anaerobic, gram-negative bacterium commonly found in the healthy oral, gastrointestinal and genital flora of humans. The endometrial microenvironment coincides with increased Fusobacterium and increased numbers of myofibroblasts (the cells making up excess womb-like tissue) with high TAGLIN expression. TAGLIN is a gene whose protein product (TAGLIN) helps cells proliferate and migrate elsewhere in the body. This may explain why the tissue grows as it does in endometriosis. The gene’s activity is also boosted by inflammation which occurs during a bacterial infection.

The study is a recent example of growing interest into the impact of the microbiome on disease. Elise Courtois, a genomicist studying endometriosis at the Jackson Laboratory in Connecticut, admits that when it comes to the poorly understood disease, ‘genetics doesn’t explain everything.’ The data supports a mechanism for the pathogenesis of endometriosis and the researchers suggest that ‘eradication of this bacterium could be an approach to treat endometriosis.’

While this evidence is important, more work needs to be done before we are able to use it to develop treatments for the disease. As Krina Zondervan, head of Nuffield Women’s and Reproductive Health department at the University of Oxford, states ‘we’re really at the infancy of this.’ To confirm the interaction between bacterial infection and endometriosis it would be useful to test for this association in a larger and more diverse population. Further, mice were used as the model organism in the study though cannot menstruate or form spontaneous endometrial lesions hence are limited to study condition. Despite these limitations the study is a beacon of hope for those with the disease, Krina also highlights that ‘these are really intriguing results and potentially exciting.’