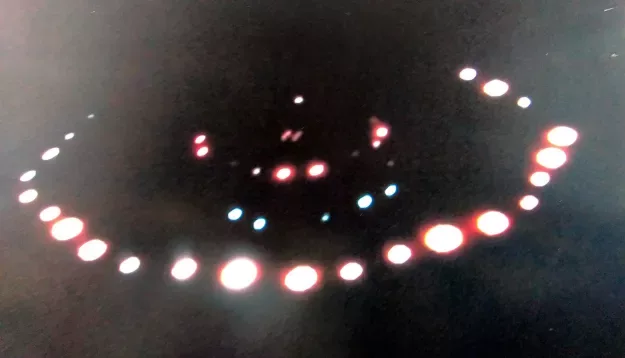

Recent ‘alien’ sightings raise the question again: how much science is there in the science fiction? Image credit: John Macdonald, flickr, CC BY 2.0.

The question of other worlds and alien lives is at the core of both great mysteries and familiar tropes. Not only does the constant scientific research remind us that we are not the centre of the universe, but popular media also exploits our scientific conjecture by appealing to the horror, mystique, and anxiety of it all. Our perceptions are shaped by what we are exposed to and what we internalise, but what exactly are we witnessing with science fiction? Is it scientific research morphed into a script, or a byproduct of vibrant and baseless imagination? To answer such questions, we must peel back multiple layers, starting with what generates our interest in alien worlds and subsequently examining how these otherworlds are portrayed on the big screen.

The question of other worlds and alien lives is at the core of great mysteries.

Scientific studies that support and solidify the possibility of extraterrestrial life have existed since the mid-20th century, but speculations about alien life date back centuries. Feeling small is part of the human experience, and early philosophers who took their time looking up at the sky have found different ways to articulate how we may just be one of the many. Classical Indian philosophy suggests different accounts of atomism based on their view of realism (the philosophical realist theories of Naiyāyikas and Mīmāṃsakas, and the heterodox realists such as the Ābhidharmikas and the Jainas). The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika theory proposed the existence of different atoms according to the elements: water, air, fire, and earth. The Jaina system, on the other hand, posited the idea of a single homogeneous matter that composes everything, and the Buddhist theory concentrated atomism on momentary events (dharmas or dhammas) instead of physical substances. Meanwhile, the ancient Greeks developed a more singular and systematic study of natural philosophy. Thinkers like Leucippus, Democritus, and Plato started to consider that our universe is merely a chance-based conjunction of atoms and recognised the possibility of similar worlds that were atomically as lucky as us.

Of course, throughout time, such philosophical hypotheses have infiltrated not only scientific thought but media as well. Alien sightings have been circulating through news outlets since the first example in 1947, in Roswell, New Mexico, when a rancher and his son came across the wreckage of tinfoil, sticks, paper, and rubber strips that were later on considered to be the remnants of a “Flying Saucer“. From then on, American sightings and reports increased drastically. In 1952, certain radar and visual sightings were recorded in Washington, D.C., near the National Airport. Between the 1950s and 60s, Area 51 in Nevada also became a hot spot for UFO sightings, reaching to a point that an archive of unidentified flying objects was released in 1952 by The United States Air Force, named Project BLUE BOOK. The project was closed in 1969 but contains information about potential sightings recorded in the 17-year period.

Feeling small is part of the human experience, and early philosophers have found different ways to articulate how we may just be one of the many.

Each claim of alien spotting has numerous conspiracy theories as well as observational explanations. Collectively, they vary greatly in reliability, and consequently interpretations depend on one’s own beliefs and biases when it comes to forming a consensus. Regardless of the speculative nature of previous documentation, the possibility of extraterrestrial life does have scientific data to support it. The estimations for Frank Drake’s 1961 Drake Equation range from 1 to several million (though Drake himself suggests the approximation of 10,000) as the number of planets in the Milky Way Galaxy that could support civilisations. While discovering Mars in 2022, NASA’s Curiosity Rover detected a type of carbon associated with biological life on Earth. Furthermore, the icy moons of Saturn and Jupiter (Enceladus and Europa) have also been the subject of study when it comes to traces of life, as the two moons are ocean worlds that have habitable conditions. Looking for evidence of past or present life, known as biosignatures, also includes studying planets outside of the Milky Way (exoplanets) through advanced technology, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). There is no singular conclusion that completely validates alien life, but the evidence up until now continuously substantiates the possibility.

Scientific studies supporting the high chance of extraterrestrial beings are perhaps one of the main motivations in their persistent media representations. Despite a lack of scientific visual evidence, aliens in all shapes and sizes have been part of our popular culture for decades. Science fiction brings forward the bounds of human imagination. Alien representations can broadly fall into four distinct categories: aggressive, exploratory, cooperative, and transcendental. H. G. Wells’ 1898 science fiction novel War of the Worlds, which is regarded as a landmark for representing extraterrestrial life, is one of the prime examples of the aggressive version. What followed Wells’ trendsetting work/War of the Worlds was a massive sub-genre formation, with the first appearance of aliens on screen in the 1902 science fiction film A Trip to the Moon.

Despite a lack of scientific visual evidence, aliens in all shapes and sizes have been part of our popular culture for decades.

Over time, an endless supply of visualized creatures has left an impression of aliens in the minds of generations. Though some depictions were hostile and fitting to the horror genre, such as the creatures in Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien and John Carpenter’s 1982 horror The Thing, some representations depicted aliens as benign and exploratory creatures, in the vein of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. the Extraterrestrial (1982). Some aliens have been easy to understand, like the ones in Star Trek (1995-), while others have been transcendental beings far too advanced for human comprehension, as Carl Sagan demonstrated in his 1997 novel Contact.

The creativity surrounding the visualization of extraterrestrial life is endless. While Jordan Peele imagined a jellyfish-esque creature who can morph itself into a classical UFO stereotype in Nope (2022), Dennis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) included seven-limbed cephalopod (highly advanced marine animals, such as octopus, squid, or cuttlefish) aliens fictitiously called “heptapods”. Nevertheless, the first image that pops into our minds when someone mentions aliens is similar to the grey-like creatures in X-Files, the Colonists. Whether it be grey or green, a typical embodiment of aliens is considered to be a short, slender humanoid with buggy black eyes and a massive triangular head. Deviations happen, but the fundamental image remains mostly intact.

From a historical standpoint, the little green men stereotype dates to a 12th-century legend known as “The Green Children of Woolpit”, where two children with green skin appear in a village out of nowhere. The green skin characteristic was later reinforced in Harold Lawlor’s story “Mayaya’s Little Green Men” (1946) and Frederic Brown’s novel Martians, Go Home (1954). Although medieval fairytales don’t possess direct links to alien representation, frequently characterising otherworldly creatures as having green skin can be traced back to folklore. The imagery gradually became a media staple of supernatural or extraterrestrial creatures with more instances surfacing, such as the Great Gazoo character in “The Flintstones” in 1965 and referenced multiple times in Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-1969) and Doctor Who (2005-2007).

Popular culture legitimised conceivable alien stereotypes with characteristics similar to human anatomy but just different enough to intimidate.

On the other hand, the next stereotype of tentacled aliens has a different backstory. As most famously seen in Arrival (2016), extraterrestrial creatures who embody an octopus-like morphology can be linked to the fact that octopuses are generally considered “alien” when compared to other species on Earth. A 2018 study titled “Cause of Cambrian Explosion – Terrestrial or Cosmic?” expanded upon the genetic complexity and mysteriousness of octopuses, suggesting a possible extraterrestrial explanation. The claim did not lead to any solid evidence that would legitimise the categorisation. Still, it did set a framework for why alien imagery draws inspiration from the appearances of octopuses.

Popular culture legitimised conceivable alien stereotypes with characteristics similar to human anatomy but just different enough to intimidate. It has created a balanced mixture of scientific speculation and the presence of aliens in the media and literature created just enough room for imaginative manipulation for the sake of a story. We read and witnessed all kinds of creatures without having a legitimate frame of reference. What science fiction proposes is not a rejection of science but an imaginative play with what it can discover. As for the true nature of extraterrestrial life forms, there are countless conspiracy theories to be discussed and explanations to be made with no conclusive answer. Do the aliens have big heads and slim figures because their advanced nature doesn’t require physical strength? Do they lack mouths because verbal communication is primitive? Alternatively, are we forcing physicality onto something that is perhaps a mere sensorial substance?

Until an advanced extraterrestrial glides by our telescopes, a spaceship glamorously lands on a random American neighborhood, or we receive a cryptic code from a malicious creature, we are left only with what human minds can conjure.

No definitive answer can be formulated for these questions, but what we don’t know can shed light on what we actually can know. What is offered by science fiction is never considered as science—but rather, it is an extension of scientific creativity. The alien worlds we consider ourselves familiar with take their inspiration from science but gather their inspiration from nature, culture, and technology. We see an amalgamation of what humans experience from a human perspective. Our imaginations can only extend through knowledge and culture accumulation. Until an advanced extraterrestrial glides by our telescopes, a spaceship glamorously lands on a random American neighborhood, or we receive a cryptic code from a malicious creature, we are left only with what human minds can conjure. That is to say, until we receive or achieve a confirmation, we are probably stuck with the little green men.