One of the major barriers in sustaining human life on the moon is growing crops. However, new research suggests that lunar soil and fungi are capable of growing chickpeas. Photo credit: Markus Winkler via Unsplash

I’m a fan of the humble chickpea. Just naming it brings connotations of health, nature, and a dash of deliciousness—but now, this unassuming legume may be hailing in a promising future. Recently, chickpea plants have been grown from what amounts to “moondust”: that is, the substance known as lunar soil. Alongside some aid from fungal and worm species, this finding supports the possibility of one day colonising our rocky neighbour.

…making it [chickpeas] the perfect candidate for the possibility of human life on the moon.

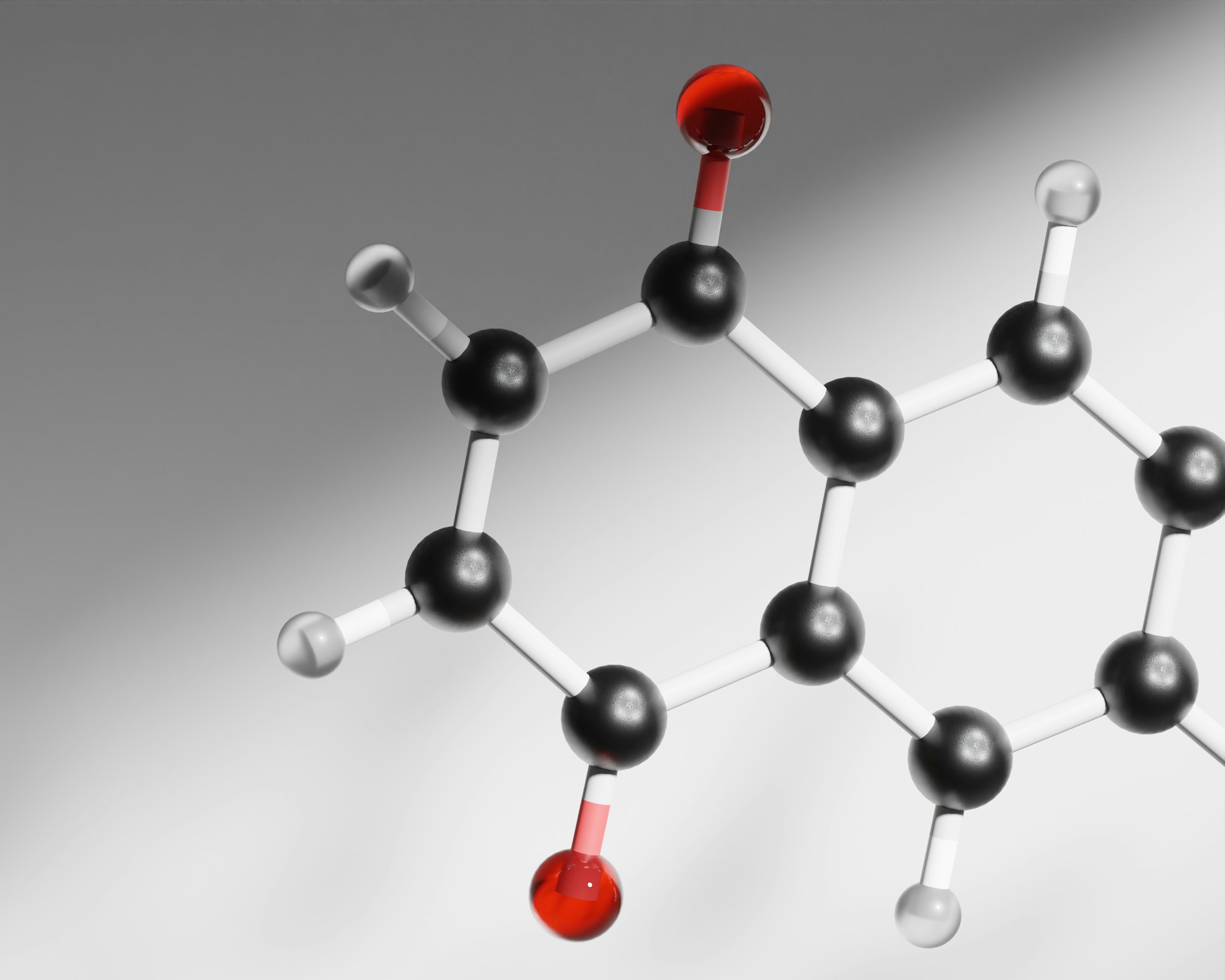

Lunar soil is typically completely incompatible with plant life. Both its texture and its contents are against it. As well as generally lacking nutrients, lunar soil contains many toxic chemicals, such as heavy metals, that we certainly would not want to be consuming. Through pioneering work with reconstituted lunar soil, however, Jessica Atkin and Sara Oliveira Pedro dos Santos of Texas A&M and Brown University respectively have managed to grow plants in lunar soil with the potential for human consumption. The object of this research, which involved the mimicking of lunar samples retrieved during NASA’s Apollo missions, was the chickpea plant. This legume is not only a staple of millions of people’s diets but is also rich in macro- and micro-nutrients, making it the perfect candidate for the possibility of human life on the moon.

Within the study, the scientists used a fungal species (Arbuscular mycorrhiza) known to form a mutually supportive relationship with the chickpea plant. In addition, this type of fungus, alongside multiple others, is adapted to scourge the soil in which it sits of toxic compounds, including the heavy metals found in lunar soil. Hence, when placed with chickpeas in a sample, the plants are protected from adverse effects. In a similar vein, the crops were also planted in the presence of vermicompost—a rather catchy name for worm manure. This substance helps the plants by providing the vital nutrients missing from the lunar soil. Worms will eat virtually anything, turning (quite literally) rags into vitaminic and mineral riches. It was the combination of these two components that brought success to the field of lunar horticulture.

Intriguingly, Atkin notes how soil quality may improve over longer test periods, with later generations of chickpea plants suffering less exposure to toxic agents. This is still yet to be tested but may mean that other plants could be grown in the soil, more akin to the variety found on Earth.

These findings raise the question of whether it should truly be our goal to jet off to the moon, or whether these findings could be applied to more earthly endeavours.

All in all, this is not only very exciting news for space travel but also may be applicable to wider fields of science. For example, the use of vermicompost may be key in supporting crop growth in arid regions, and fungi could contribute to detoxifying land exposed to nuclear waste or testing. Getting back to space though, these findings raise the question of whether it should truly be our goal to jet off to the moon, or whether these findings could be applied to more earthly endeavours. Nevertheless, if we can now grow chickpeas in lunar soil, we may soon be yielding more varied produce for the mouths of future generations—wherever they end up.