Sara Middleton

Sara Middleton (PhD candidate in ecology) is injecting the drama into grassland communities by creating a drought. This is all in the name of research to try and find out how certain plants respond to extreme conditions because, as Middleton points out, they can’t just move somewhere nicer.

The star of this “plant soap opera” that Middleton is directing has all the features you could wish for in a leading lady. This kind of research is very “data hungry” so requires a grass that is numerous, evenly spread and easy to identify individuals of – an unusual casting breakdown. But the species of grass she studies not only ticks every box but is also of high significance in ecology, acting as a rare habitat for some species of butterfly.

Middleton is currently observing 140 small areas of grassland each with numerous individuals. To determine how they deal with drought she’s looking at the functional traits (such as size and height) and tying this into demography (survival, growth and reproduction).

An artificial drought has been created by Middleton and co-workers using small, tent-like shelters periodically for the past 4 years. Now it’s nearly time to collect the results, with one method of gathering data almost as showbiz as the grasses themselves… Drones!

Middleton explains how when plants are stressed (i.e. short of water) they signal to the stomata (tiny holes in the leaves) to close, to stop the exchange of gas and escape of water. This change is imperceptible to the human eye but easily seen by a drone with a light sensitive camera.

Soon Middleton and her group will be launching these drones to find the answers that are four years in the making and see how these soap opera divas cope under the pressure of drought.

Sriraj Aiyer

Metacognition, Sriraj Aiyer (experimental psychology researcher) explains, is your thoughts about your thoughts. It’s the word for when you’re trying to remember the name of that actor from that film, the awareness of knowing that you know and it’s just on the tip of your tongue.

The kind of metacognition Aiyer is most interested in is the confidence people have in their own decisions, something it turns out you can actually measure scientifically.

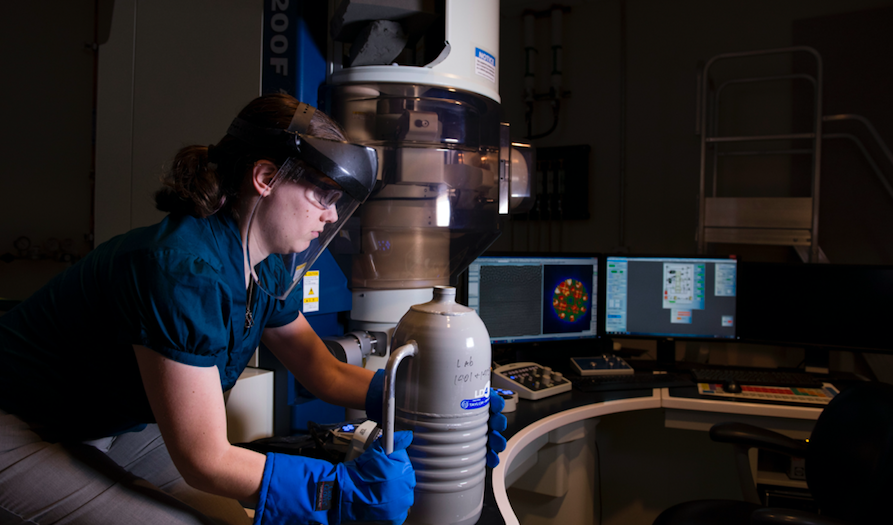

In Aiyer’s research he gets participants to make a simple choice, asking them which box (left or right) has the most lights on it. While they’re making this decision an EEG cap measures the voltage in their brains, which 300ms after the decision shows a negative peak. This is what Aiyer calls “error related negativity” and is a visualisation of the thought that a mistake has just been made.

Aiyer then asks participants to rate their confidence in their decision before throwing a spanner into the works – two algorithms with some helpful advice. One says it thinks the left box is correct, one says it thinks the left box is correct with 75% confidence. In reality both algorithms are the same but interestingly, under time pressure, multi-tasking or even with a monetary incentive, the one with more detailed advice is always more trusted.

This link between trust and confidence is at the root of what Aiyer is trying to demystify. As the world becomes more automated the relationship between humans and systems we can interact with becomes more key to the smooth running of everyday life. Under-trust and we slow progress, over-trust and we find ourselves at the risk of letting a mechanical error cause serious damage.

While similar research has already been done in complex situations such as with military pilots, Aiyer is more interested in day-to-day interactions which are becoming more common. How much trust do people put in systems? How does this affect behaviour and what are the neural underpinnings of the effect? Answers to questions such as these could be the key to a harmonious future of humans and automated systems working together.

Elisa Granato

“Micro-wars! How bacteria kill each other” was the title of Elisa Granato’s talk and it was no less cool than it sounds. Granato describes her work as basically managing a bacteria fight club. She pitches colonies against each other and watches on through a microscope into the arena to see who comes out on top.

In nature, Granato explains, bacterial cells are always surrounded by other cells. Limited space and food means there’s great competition to stay alive. To be a good competitor you have two options – grow faster than your rivals or simply kill them all!

Unsurprisingly, it’s the killing tactic that peaks Granato’s interest. She describes a huge arsenal of molecular weapons that bacteria can wield. There are short range molecular species with poisoned tips but these are contact dependent. Granato’s personal favourites are the long range weapons, toxic molecules that bacteria secrete. Particularly, she’s interested in a kind of bacteria that fill themselves with toxins, turning themselves into tiny bombs that explode, taking out all cells around them and killing themselves in the process.

At first glance, this seems like a very counterproductive survival technique, especially considering that when two strains meet, 95% of the colony with the ability to explode like this do so. Firstly, though, it’s good to consider in what situations bacteria might do this. This is something that only occurs as a last resort. When the DNA of bacteria gets damaged it can be repaired to some extent. Sometimes the damage is so great they know there is no chance they would survive – this is when they transform into toxic bombs.

This method of fighting also makes a lot more sense when you consider that bacteria are clonal. Each bacterial cell is a clone of another within a colony, so even if 95% die, their spirit (and exact genetics) will live on in the remaining 5%.

Of course, when we say “know” we don’t mean the bacteria are sentient, just that they are responding to damage and to the presence of certain molecules around them. This opens the door to many possibilities. Granato agrees excitedly with a questioner that if we could manipulate these conditions to make these bacteria attack when we want them to, they have excellent potential to deal with problems like antibiotic resistance.

It seems there’s a lot more to this research than just watching two colonies at war (though that, in itself, is pretty cool).