Figuring out the composition of the bacteria in the gut, mouth, and on the skin is very fashionable at the moment, with papers regularly linking the microbiome to an unexpected disease. However, I can’t help but wonder if microbiotics isn’t the magic wand we were hoping for. Will it stand the test of time?

Studying the microbiome (‘the hidden organ’) has recently become increasingly popular thanks to advanced, low cost DNA sequencing techniques. It has even been possible for the Human Microbiome Project Consortium to characterise the bacteria of nearly 5000 specimens from healthy adults, to get an idea of normal microbiome composition.

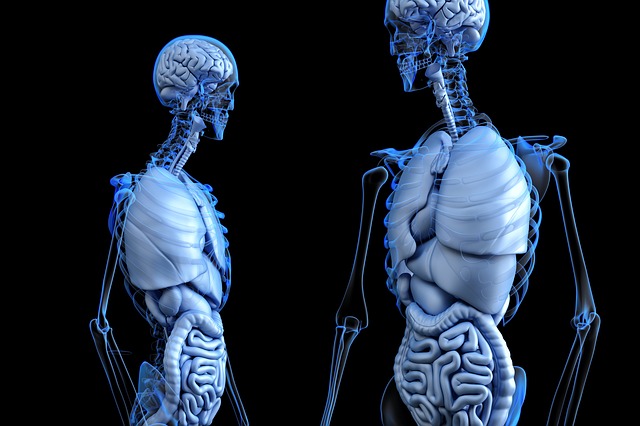

We know that the bacteria with which we share our bodies are important. After all, the human body is thought to contain the same number of bacterial cells as human cells- around 40 trillion. So it’s pretty likely that they play a significant part in our physiology. Take C.difficile, for example. This nasty bacteria is common in hospitals and may cause diarrhoea after a course of antibiotics. The drugs kill off the friendlier bacteria in the gut, allowing C.difficile to run riot. It’s easy to see how the gut microbiota may be linked to gastrointestinal diseases too, like irritable bowel syndrome.

What’s weirder is the association between a dysregulated microbiome and conditions like autism. One study found that when pregnant rats were injected with bacterial molecules the offspring showed autism-like behaviours, such as social deficits. Intriguing. It’s also exciting to think that Parkinson’s disease (PD) may stem from abnormal gut bacterial composition, in addition to changes in the brain. This has led to the idea of the gut-brain axis. The intestinal tract and the brain are physiologically and anatomically worlds apart, except for the vagus nerve. However, it’s possible that αSyn, a compound that causes damage to the motor areas in the brain of PD patients, originates in the gut and travels up this ‘wandering’ nerve to the central nervous system.

These ideas are fascinating, but are they far-fetched? Unfortunately, we can’t get ahead of ourselves. There are many issues still to be solved, such as what defines a healthy microbiome? Is there too much global variation to link it to anything significant? Also, in line with science’s favourite mantra, correlation does not mean causation. For example, the bacterial imbalance seen in inflammatory bowel diseases could just be a consequence of specific diets, rather than a cause of IBD.

As with most things in medicine, the microbiome is probably interacting with several genetic and environmental factors to cause disease, blaming the bacteria in all instances is just a quick fix. Going forward, more research needs to be done to establish causal relationships and avoid commercialisation of ideas that don’t quite add up yet.

It seems we’ve just got to watch and wait.

Further information:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bdrc.21118/epdf

http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/43/10/1557.long#ref-157

http://pmj.bmj.com/content/92/1087/286.long

https://www.nature.com/news/microbiology–microbiome–science–needs–a–healthy–dose–of–scepticism-1.15730

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3564958/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5045145/