Amidst the first stages of negotiation on the Global Plastic Treaty, alarming new research on the extent of microplastic pollution in Antarctica illustrates the urgent need for global policy reform in relation to plastic pollution.

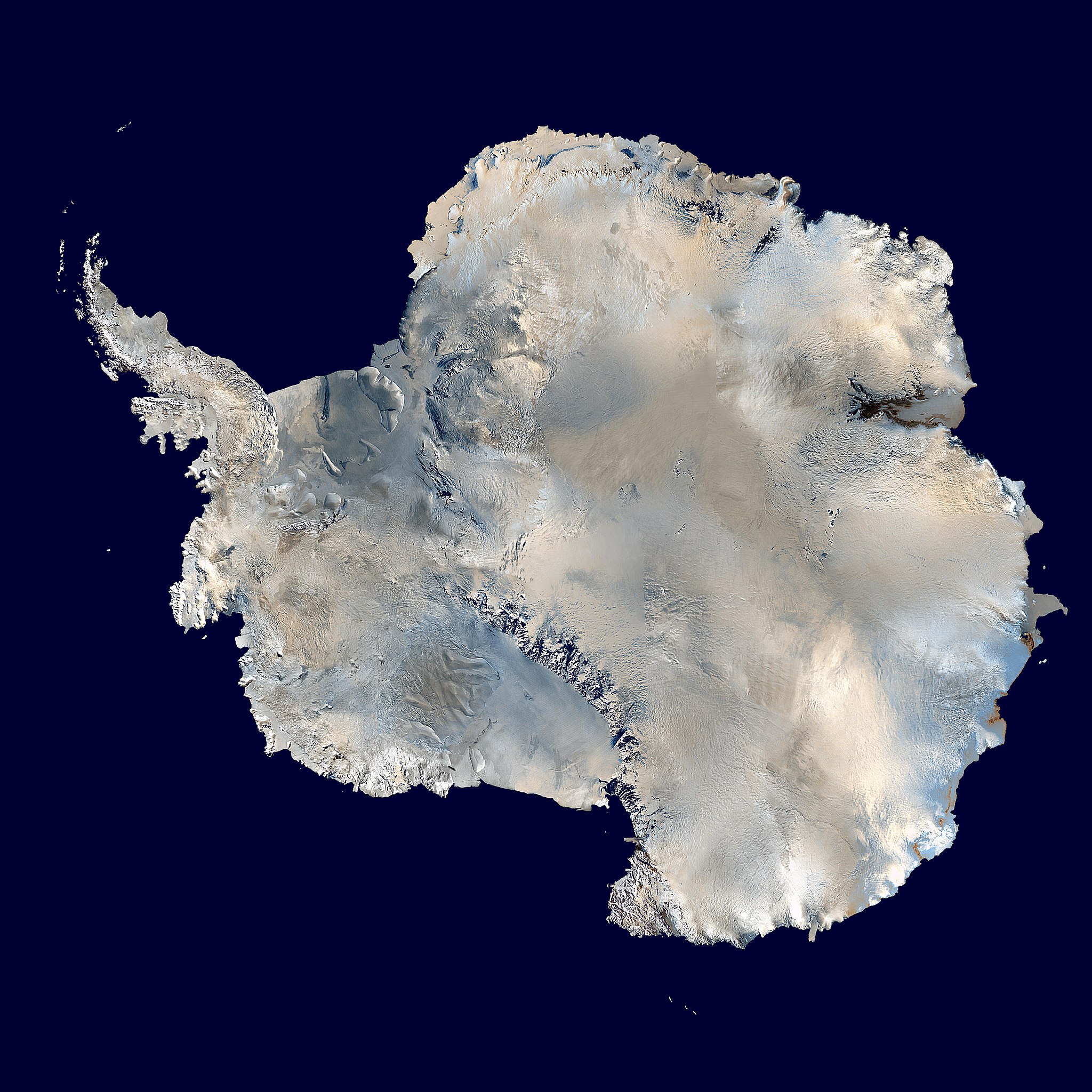

Antarctica is commonly referred to as the ‘pristine’ continent. It is the only continent remaining that has never sustained a permanent human population and was considered, until recently, “one of very few places on Earth that has been minimally affected by anthropogenic activities”.

In 2020, a team of atmospheric scientists at Colorado State University genetically analysed microbes in samples of Antarctic air, demonstrating that the significant majority of airborne microorganisms had local marine origins.

Research scientist Dr Thomas Hill, co-author of the paper, ultimately concluded that Southern Ocean air which surrounds Antarctica was free from particles caused by human activity, linking this to protective ocean currents that circulate the continent.

A mere 2 years later, research carried out in collaboration between the University of Oxford and Nekton—a marine conservation non-profit organisation—has revealed that even Antarctica, the continent most isolated from human activity, has become ubiquitously contaminated with microplastics.

All samples taken of air, seawater, sea ice, and sediment of the Wedell Sea were shown to be polluted with synthetic fibres.

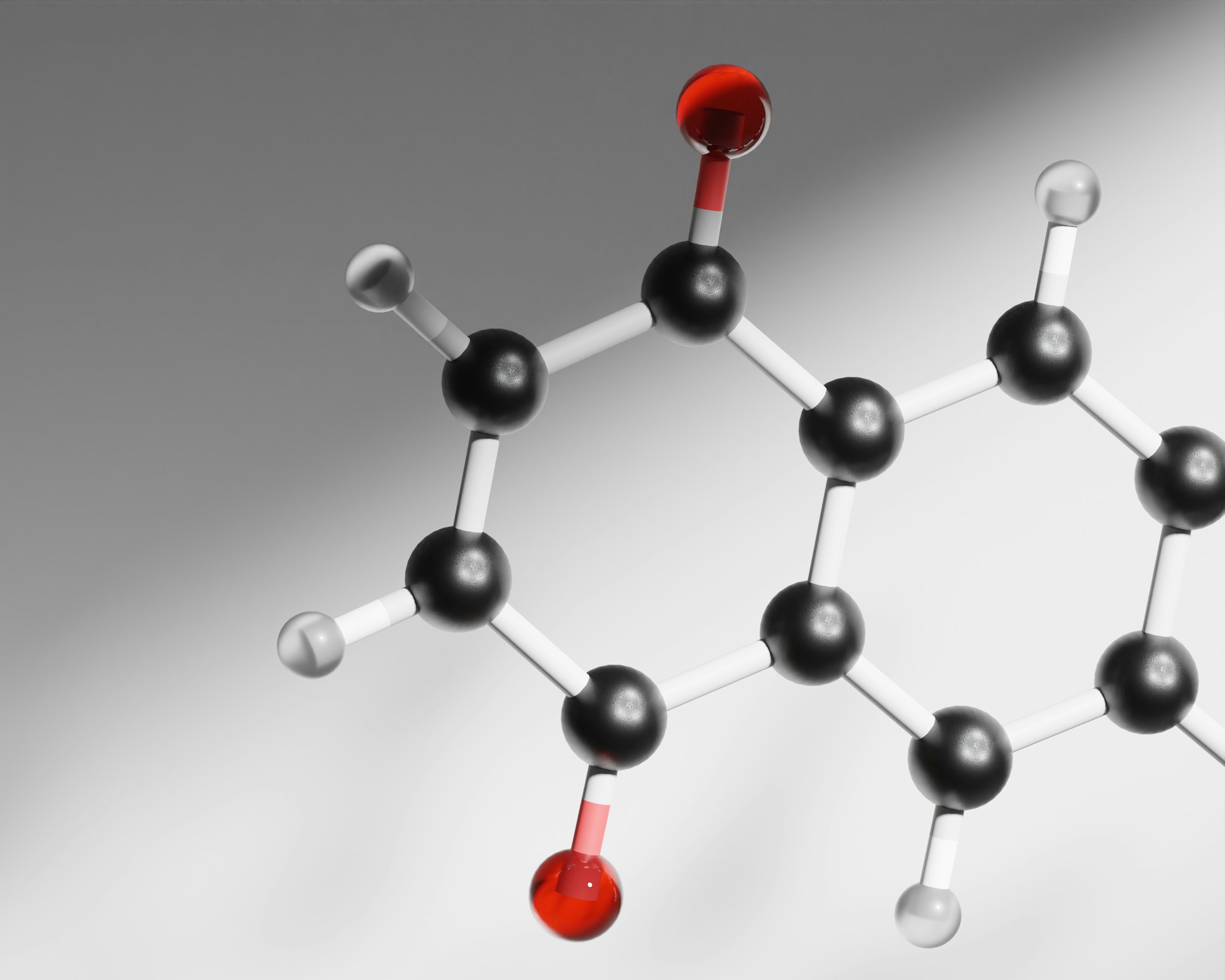

Researchers were able to detect the presence of microplastics via optical and chemical analysis, the most common of which being polyethylene terephthalate (PET), whose primary source is traced back to land-based synthetic textiles.

The fast fashion industry is cited as a notable contributor, as synthetic fibres are released into global water systems upon manufacturing and washing.

Microplastic contamination has numerous consequences on the Antarctic ecosystem. Deposited microplastics are speculated to accelerate the melting of polar regions, as coloured particles cause increased absorption of incident solar radiation.

Airborne particles can influence the polar climate by acting as ice nuclei, triggering the formation of atmospheric ice crystals in clouds and disrupting natural cloud formation processes.

Most concerningly, microplastics interfere with Antarctic food chains. Krill, which form the foundations of the polar food web, digest microplastics into nanoplastics and result in the accumulation of plastics in tissues of all marine animals.

These findings paint an incredibly bleak picture of the state of global plastic pollution.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the world’s largest ocean current that flows clockwise around Antarctica, can no longer protect the remote continent from the sheer volume of plastic pollution now circulating in our oceans and air, as was previously assumed.

According to the authors of the paper, attempting to remove microplastics from nature is inherently futile; they are by definition microscopic and hence would be a hugely costly, disruptive, and inefficient process.

This does not mean, however, that all hope is lost. Dr Lucy Woodall, Associate Professor at the University of Oxford and co-author of the paper, stresses the importance of preventing microplastic pollution at its source.

By understanding the transportation pathways that land-based contaminants follow through air and ocean currents, the origin of these microplastics can be traced and ultimately intercepted. According to environmental scientist Alex Aves, this may be a particularly important approach since atmospheric modelling suggests microplastics found in Antarctica may have travelled for thousands of kilometres to reach the continent.

This research comes at a pivotal point in climate change policy. The primary round of negotiations (INC-1) for a global, legally binding plastic treaty ended on the 2nd of December in host country Uruguay and will resume in Paris in 2023.

The latest findings emphasise the gravity of the task at hand. Policy makers and scientists must collaborate internationally and with haste to prevent the contamination of our entire planet.