Can AI be harnessed as a positive tool to protect creative fields? Photo credit: Google DeepMind via Unsplash

The livelihoods of Britain’s creatives are in a precarious position. Freelancers and part-timers dominate the industry, eking out a living in a sector notorious for instability. In 2023, 43% of nearly 6,000 musicians surveyed earned less than £14,000 of their annual income from music. For visual artists, the median income barely reached £12,500. Film and TV workers fare no better. In July 2024, eight months after the SAG-AFTRA strike ended, a survey of 3,300 people revealed that over half remained unemployed. Of those still working, 94% were underemployed. ‘The last job I did was part time, with a pay cut, with multiple roles rolled into one and a drastically reduced schedule,’ said a DV Director- cum- Assistant Producer.

Image generators have driven visual artists to despair.

Against this backdrop of financial fragility, AI-generated content is poised to take off at the expense of creatives. Image generators have driven visual artists to despair. ‘It can only mean the death of being a professional artist,’ a survey respondent told the Design and Artists Copyright Society. According to the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers, musicians could lose $10 billion in revenue by 2028, audiovisual creators another $12 billion. The market for AI-generated content is projected to balloon by $61 billion over the same period.

The UK’s intellectual property and data protection laws should, in theory, protect creators and content owners. But many creatives accuse Silicon Valley tech giants and local generative AI startups alike of sidestepping these safeguards when training their models. They argue that automated programmes have systematically scanned and extracted vast amounts of creative content from the internet—text, images, music, and video—feeding this data into models that analyse patterns to generate new outputs. For example, in separate complaints against Microsoft and Stability AI, the New York Times and Getty Images allege that millions of their articles, photographs, videos, and illustrations have been used. More importantly, they, and many others who have yet to enter the courtroom, suggest that this has been done without their permission nor fair compensation.

London-based Stability AI’s former Head of Audio, Ed Newton-Rex, resigned in protest in 2023 over disagreements with the company’s position on this ‘exploitative’ practice. Educated at Cambridge’s Faculty of Music and founder of Jukedeck, an AI music generator startup acquired by Bytedance in 2019, Newton-Rex has launched a campaign against violations of copyright and performance rights. He asserts that ‘the unlicensed use of creative works for training generative AI is a major, unjust threat to the livelihoods of the people behind those works.’ Furthermore, as these models grow more sophisticated, they will require increasingly high-quality data to maintain their edge. This is a trend evident in the rapid expansion of models like GPT, which had 1.5 billion parameters in 2019 compared to a suspected 1.8 trillion in 2023. To curb continued unauthorised use of creative content, over 40,000 signatories, including Thom Yorke, Stephen Fry, and Alan Ayckbourn, have backed his push for stricter enforcement.

The government sympathises to a certain extent. Launching an open consultation on Copyright and AI in December 2024, the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology declared: ‘This status quo cannot continue.’ For Britain’s creative sector, that statement rings true—but not because copyright law is inadequate, as the consultation implies. Author Kate Mosse insists, ‘Copyright laws are robust, fit for purpose, and protect originality, excellence, and innovation.’ Organisations like the British Copyright Council, Directors UK, and Equity all agree. Their contention? The law exists but has not always been enforced.

Yet, the government is considering an ‘exception’ to copyright law: one that would let AI firms train their models on copyrighted content unless rights holders explicitly opt out. A similar system in the EU has led to widespread, unpunished ‘illegal scraping‘. The burden has fallen on European creatives to actively reserve their rights, monitor for breaches, and fight violations—a costly and impractical task for freelancers and small businesses. Few have the resources of The New York Times, which spent $10.8 million in 2024 battling OpenAI and Microsoft over copyright infringement.

The burden has fallen on European creatives to actively reserve their rights, monitor for breaches, and fight violations…

The government is caught in a dilemma. Even while the median creative struggles, the industries in which they work are booming, contributing £119.6 billion to the UK economy in 2023, and growing at a rate 13 percentage points higher than the UK economy as a whole. However, AI also promises productivity gains of 0.9-1.5% per annum, potentially adding £630 billion to the UK economy by 2035. Pact, the union for independent film and TV producers, believes the government should be ‘incentivising licensing solutions’ to ensure rights holders are fairly compensated. But the consultation dismisses this approach, warning it would make Britain ‘significantly less competitive‘ in AI, adding compliance costs and legal risks that stunt innovation.

A technological solution could, in theory, satisfy both sides. One proposed fix is the International Standard Content Code (ISCC), which assigns unique, permanent identifiers to digital assets. This would allow rights holders to track how their content is used and enforce copyright protections more easily. But there are hurdles. ‘This situation is new, and people need to get familiar with the technology,’ notes Sebastian Posth, one of the ISCC’s co-creators. Rights holders, particularly independent creators, may lack the capacity or technological know-how to implement such a system at scale.

AI startups, too, are wary. Widespread adoption of a single technical standard is crucial before they commit to integrating it. ‘Until we have those sorts of technical solutions, it puts startups in a very difficult position,’ says Vinous Ali, Deputy Executive Director of the Startup Coalition. And then there’s the problem of past transgressions. Stability AI, engaged in a legal battle with Getty Images, argues that it currently lacks the resources to identify all copyrighted works in its datasets. Even if a robust registry and tracking system were to be put in place, historical infringements may remain unresolved.

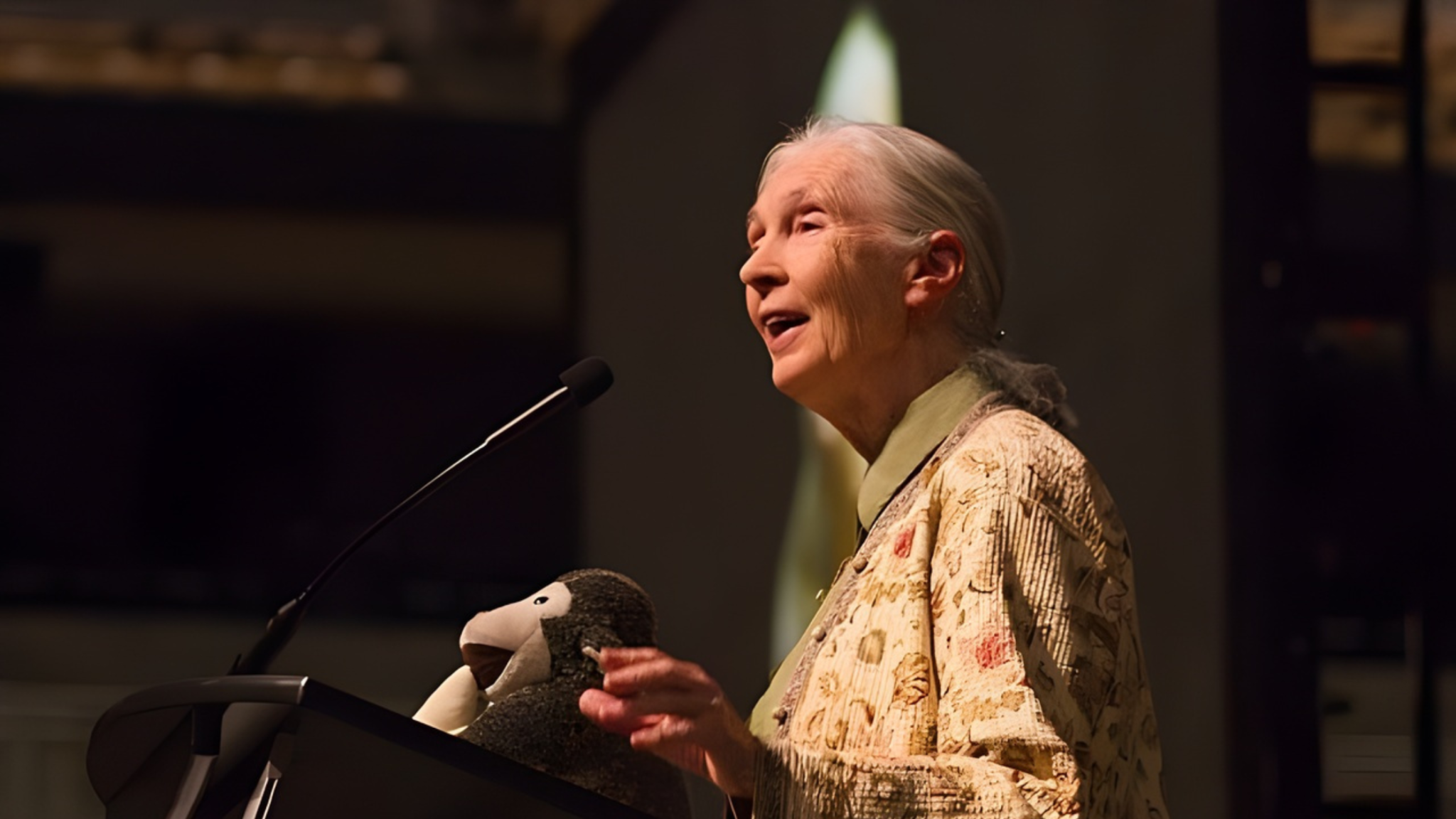

Still, the battle lines aren’t as rigid as they seem. The Creative Rights in AI Coalition frames the future differently: ‘Ours is a positive vision, a vision of collaboration between the creative industries and generative AI developers, where we can all flourish in the online marketplace.’ This suggests that AI does not have to be a threat to creatives; it can also be a tool to be harnessed. Jane Feathersone, TV Producer and founder of Sister Pictures suggests that ‘AI skills [are] essential for the future of the industry’. Benjamin Field, Executive Producer at Deep Fusion Films, appears to agree and is collaborating with the National Film and TV School on an AI filmmaking course.

…many creatives already use both predictive and generative software to streamline workflows.

In fact, as the edits to Adrien Brody and Felicity Jones’ Hungarian accents in The Brutalist have made us aware, many creatives already use both predictive and generative software to streamline workflows. ‘These tools have been used in the sector for a long time,’ says BFI CEO Ben Roberts. Publishers, too, see AI’s value. ‘We are using it to drive efficiencies, understand our customers better, for new product development, and for creative solutions,’ says Professional Publishers Association CEO Sajeeda Merali. But the consensus among creatives remains clear: the laws are fine as they are; rights must be enforced. ‘The UK should not pursue growth and innovation in AI whilst running roughshod over existing copyright and data laws,’ warns Anna Ganley, Chair of the Creators’ Rights Alliance.