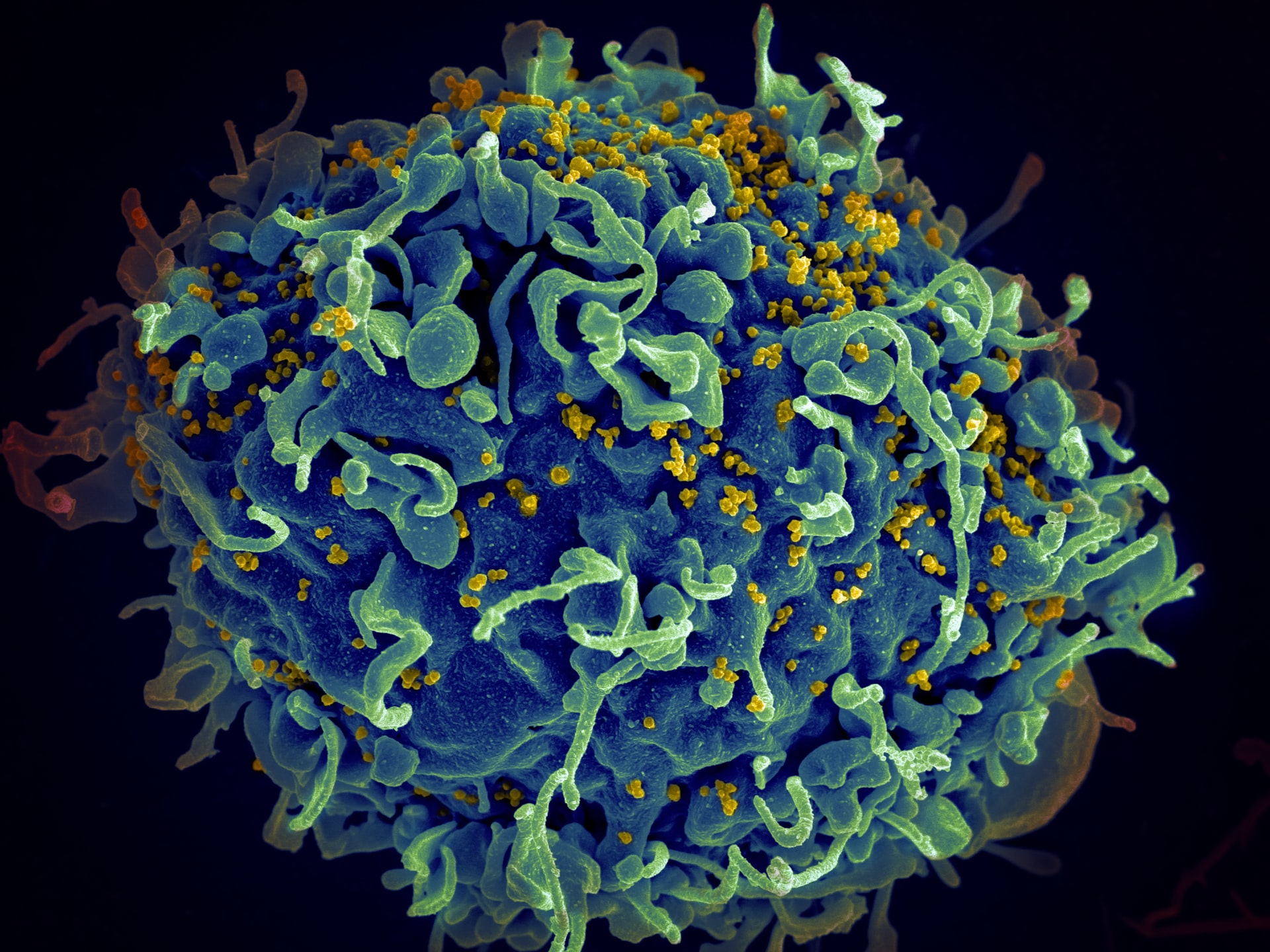

Image description: Human T cell (blue) is under attack by HIV (yellow), the virus that causes AIDS (NIH).

By Eliott Thompson

This article was originally published in The Oxford Scientist Michaelmas Term 2021 edition, Change.

When discussing HIV, the term ‘the gay community’ often crops up. The gay community ‘accepts’ or ‘rejects’ something, it becomes enraged at lack of progress or vilification, it fights for its rights. What this terminology does is reduce a necessarily diverse community into a homogenous whole. There is no ‘gay community’ that thinks harmoniously, there are constant tensions and splinters. The indeterminacy of opinion and the widespread, diverse nature of gay men—and the queer community in general—is a core part of common identity. It is notable that this inherent diversity tends to be overlooked in the history of HIV. Namely, this refers to the (sub)conscious erasure of HIV activists from the memory of HIV medicalisation. Whilst there may be multiple reasons for this, I will focus on how the narratives of gay homogeneity have contributed to a history of HIV written by pharmaceutical companies, not gay men.

This is most evident in the history of Azidothymidine (AZT), the first approved HIV treatment. Originally an abandoned cancer treatment, AZT was proposed as an HIV treatment by Wellcome in 1984. After being fast-tracked through the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process in a record 20 months, AZT was presented in 1987 as an effective HIV treatment, claiming to reduce mortality. This soon became Wellcome’s highest selling drug. In 1987, the company’s share price jumped from 73.5p to 374.5p upon news that AZT would be highly priced, at about $188 per 100 capsules for Americans. By 1992, the drug sales topped $1.4 billion, with around 180,000 patients on the treatment worldwide. But faith in this drug was groundless – as proven by the 1993 Concorde study, the largest study of AZT to date with 1749 participants. The study found that across three years, 79 individuals died in the AZT group compared to 67 in the placebo group, with those on AZT having far worse side effects. The drug was extremely toxic, causing cell depletion in bone marrow meaning patients could need frequent blood transfusions to survive, while the general side effects mimicked the symptoms of progressing AIDS—the treatment killed quicker than the disease itself. The Concorde study showed that at best AZT had no positive effect, and at worst it accelerated mortality rates. Wellcome insisted it was still effective as an AIDS treatment. A spokesperson stated, ‘we agreed to disagree [with the study]. There are a lot of HIV-positive patients who are being told the drug now doesn’t work. That isn’t acceptable’. But this was insufficient to quell protests. In the eyes of activists, this proved the pharmaceutical companies’ indifference in the face of gay suffering.

The indeterminacy of opinion and the widespread, diverse nature of gay men—and the queer community in general—is a core part of common identity. It is notable that this inherent diversity tends to be overlooked in the history of HIV.

In the UK, one of the most unique protest groups was ‘Gays Against Genocide’ (GAG). The name stemmed from the group’s belief that Wellcome’s influence over mainstream gay organisations through strategic funding had “sacrificed” gay men for profit. GAG was a grassroots movement of HIV-positive men who undertook a mass flyposter campaign around London in 1993, denouncing the CEO of the Terrence Higgins Trust Nick Partridge. The Terrence Higgins Trust was the first and largest HIV charity dedicated to promoting safe sex and care for gay men with the disease; it was targeted by GAG because of a series of misleading pamphlets funded by Wellcome were produced in 1992 extolled the virtues of AZT over any other treatment, despite the many risks attached. The Trust was thus denounced as an ‘AIDS Gestapo” coercing vulnerable and scared people into taking AZT. GAG claimed responsibility for a paint bomb attack on the Terrence Higgins Trust building. The group picketed the Great Ormond Street Hospital over their use of AZT on HIV-positive babies, and, following the 1993 Concorde study, protested outside the Trust’s headquarters for weeks, demanding the resignation of the CEO. Partridge was GAG’s main target, accused of ‘pimping a poison’, and being personally responsible for the avoidable deaths of hundreds of people. After being accused of sending Partridge a guillotine by post, they stated, ‘it was in fact a novelty penis-chopping gimmick from an Amsterdam porn shop, and not a sinister threat’. One of GAG’s posters depicts an instance of police intervention: on 28 April 1993 the police were called by the Trust’s Head of Personnel over ‘GAG displaying a blow-up doll with a necklace of AZT capsules, wearing a sash that says ‘Miss AZT’. Three protestors were arrested, later stating that police officers ‘threatened to “knock [them] out”’. Whilst this is only one side of the story, the clash exposes the divergence between radical and mainstream gay activism: the overt campiness of a blow-up doll with an AZT necklace diametrically opposes an institution that feels secure enough to use the police against other gay men.

As with most HIV activism, GAG has been confined to the dustbin of history. The group is rarely brought up in discussions on the history of HIV. Instead, contemporary histories position incremental acceptance of individuals with HIV as a direct result of medical developments. The toxicity of AZT is now widely accepted, yet the actions of GAG are still perceived as unacceptable, and while the group’s reputation is one of fringe subversives. GAG is seen as a threat to the continued liberation of the gay community, a nasty underbelly that threatened to expose the entire group to homophobic attacks. Heterogeneous elements such as GAG presented potential threats to the view of a gay community that is desperately fighting for survival. In an interview earlier this year, writer Russell T Davies stated that antiretroviral drugs (such as AZT) ‘transformed public attitudes to homosexuality’ in the 1990s because HIV ‘legitimated’ homophobia—having effective treatments cancels out homophobia because they were no longer a ‘disease, ugly, [or] wrong’. Whilst an understandable position, this, in effect, defines gay history in terms of heterosexual palatability: the narrative of increasing liberation through medicine ignores swathes of vital history. This is why it’s so important to assert the significance of HIV activists in the age of medical advancements—they are central to the history of modern homosexuality as much as, if not more than, Wellcome.

The toxicity of AZT is now widely accepted, yet the actions of GAG are still perceived as unacceptable, and while the group’s reputation is one of fringe subversives.

The critics of GAG and similar groups tend to overlook the human element of their concerns. Public attitudes towards the disease sentenced the HIV-positive to death upon diagnosis. In this climate of fear, AZT was posited as the cure, although soon snatched away and labelled as more toxic than the disease itself. The UK government’s ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ (1987) advertising campaign persistently reinforced this belief. John Hurt’s foreboding voiceover states how HIV spreads through sex with an ‘infected person’ and footage pans to ‘AIDS’ chiselled onto a tombstone. Listening to the testimony of the HIV-positive hammers home the human impact of this messaging, and the 1993 Wellcome open forum on AZT is particularly insightful. One attendee screamed, ‘this is my life and I have waited ten years’; another ‘hoped to see Wellcome at the Nuremberg trials’. Most poignantly, an anonymous individual wrote on a question card, ‘I have been HIV positive for six years, taking no treatment. All my friends who took AZT are dead. How do you explain that?’. The panel had no explanation. Similarly, GAG founder Michael Cottrell stated that upon walking into the Terrence Higgins Trust ‘the first thing they did was hand us booklets saying arrange your affairs and make a will’. He described their actions as ‘lighted cigarettes’ being thrown at HIV patients telling them to ‘go fucking die’.

This element of HIV activism is the reason why their excision from the history of HIV is troubling. It’s the actions of gay men who felt unrepresented, who held legitimate fears for their own mortality and felt visceral frustration towards healthcare providers who seemed to flippantly change advice. Not acknowledging this fails them as individuals, and gay history as a whole. Historians must distance themselves from narratives of community homogeneity. It adds nothing to histories of gay men. GAG was scared, belittled, reactionary, and unapologetically loud in the face of ‘corporate’ gay culture which fought for acceptance and survival, albeit on heteronormative terms. Elevating one above another does not do justice to the complexities of modern gay history and creating a dichotomous narrative of good triumphing against bad in the battle against HIV benefits no one.

It’s the actions of gay men who felt unrepresented, who held legitimate fears for their own mortality and felt visceral frustration towards healthcare providers who seemed to flippantly change advice. Not acknowledging this fails them as individuals, and gay history as a whole.

Earlier this year, Oxford University began human trials for an HIV vaccine based on recent advances in vaccine technology. This has been praised as a breakthrough—but could it be too late? The history of HIV treatment is marred by pharmaceutical companies exploiting the trauma of gay men. One must wonder where the new Oxford vaccine sits in this timeline of events. Will it be another instance of gay trauma turned into profit, or will it be truly centred around the needs of the patient this time? Time will tell. But how much patience is left?