By Amy Stonehouse

This article was originally published in The Oxford Scientist Michaelmas Term 2021 edition, Change.

Alzheimer’s, a disease which (as of 2019) affects over 850,000 in the UK, is the leading cause of dementia worldwide. It is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily affects the brain and leads to an irreversible deterioration in cognitive function. The main symptoms of the disease include memory loss, poor judgement, and the inability to complete simple day-to-day tasks. Alzheimer’s is progressive and before the approval of Aducanumab by the FDA (food and drugs administration) on the 7th June 2021 no medicines available could treat the disease, instead focusing on symptomatic relief.

Not only is [Aducanumab] the only drug to be released onto the market to treat Alzheimer’s since 2002, it is also the first drug that aims to treat and prevent the progression of the disease instead of just providing palliative treatment.

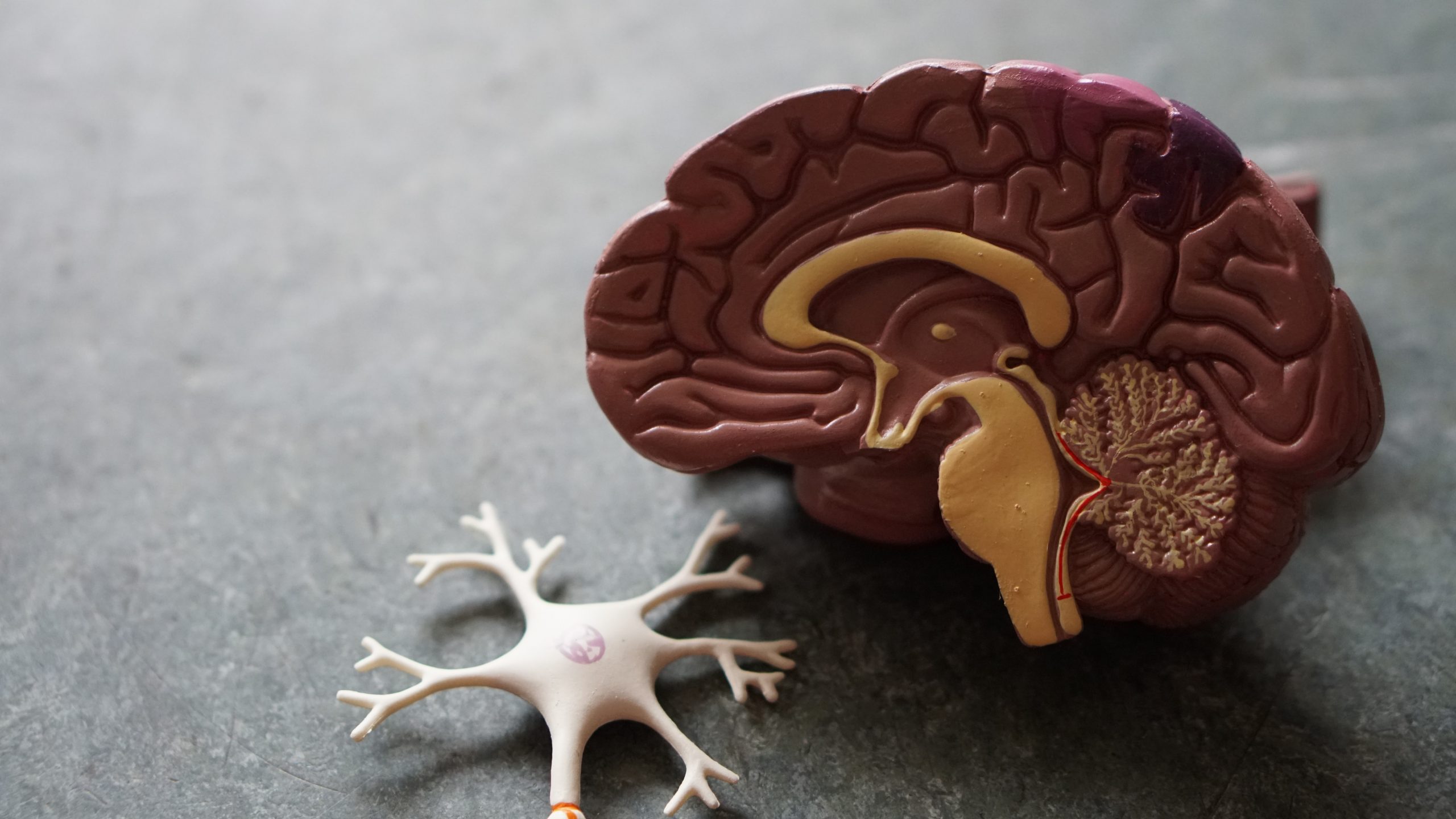

The exact mechanism of Alzheimer’s remains up for debate. The main hypothesis centres around the ‘beta-amyloid theory’ which is based on scans that show plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) is a protein found in the fatty membrane that insulates nerve cells and has a role in neural growth and repair. APP is cleaved by enzymes into smaller peptides, one of which being Beta Amyloid. This Beta Amyloid peptide is toxic and causes neuronal death and eventually the formation of plaques consisting of the degenerating neurones and beta amyloid peptides. These plaques are a hallmark indicator of Alzheimer’s disease and are thought to disrupt neuronal communication and activate immune cells leading to damaging inflammation.

Neurofibrillary Tangles are also commonly seen in the brains of Alzheimer’s sufferers; these tangles consist of microtubules (threads of protein within a cell that are responsible for the transport of structures within a cell) that are bound to proteins and become entangled causing further disruptions in cell signalling.

The presence of neurofibrillary tangles and beta- amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s patients has been known about for a long time, so why are new treatments so hard to come across?

Many factors are to blame for the gross lack of treatments available, one of the main being the progression of the disease itself: Alzheimer’s can develop in the brain for up to 20 years before the first signs of cognitive impairment appear. This has implications when pharmaceutical companies undertake clinical trials (testing) for an early-stage Alzheimer’s drug as participants to trial the drug are hard to identify.

However, the FDA have stated that there were ‘residual uncertainties regarding clinical benefit’ from the reduction of these plaques as the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s may not be totally correct.

Another huge problem, as mentioned above, is the lack of understanding about Alzheimer’s mechanism of action in the body. It is not known whether the hallmark indicators of Alzheimer’s (Beta Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) cause mental deterioration or whether they are formed in response to the cognitive decline. How can we design a drug to treat a disease when we don’t fully know how the disease works?

Despite these difficulties Aducanumab (also known as Aduhelm) was approved on the 7th June 2021 by the FDA for use on Alzheimer’s patients in the United States. Not only is it the only drug to be released onto the market to treat Alzheimer’s since 2002, it is also the first drug that aims to treat and prevent the progression of the disease instead of just providing palliative treatment. Aducanumab is an artificial antibody which binds to beta amyloid plaques. Upon binding to the neurotoxic plaques, the antibodies trigger the immune system to breakdown these deposits in the aim of preventing nerve cell damage.

Could this drug end the 19-year drought on Alzheimer’s treatments and potentially spark the manufacture of better drugs in the future? Aducanumab was approved under the FDAS Accelerated Approval Program: a program designed for the approval of drugs to treat serious conditions that have no alternative treatments. The drug was primarily approved because phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Biogen showed that it is effective in decreasing Amyloid plaques in the brain. However, the FDA have stated that there were ‘residual uncertainties regarding clinical benefit’ from the reduction of these plaques as the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s may not be totally correct.

Only time and more clinical trials will be able to indicate Aducanumab’s effectiveness as an Alzheimer’s treatment, but, at the very least, it is a stepping stone to one day curing Dementia.