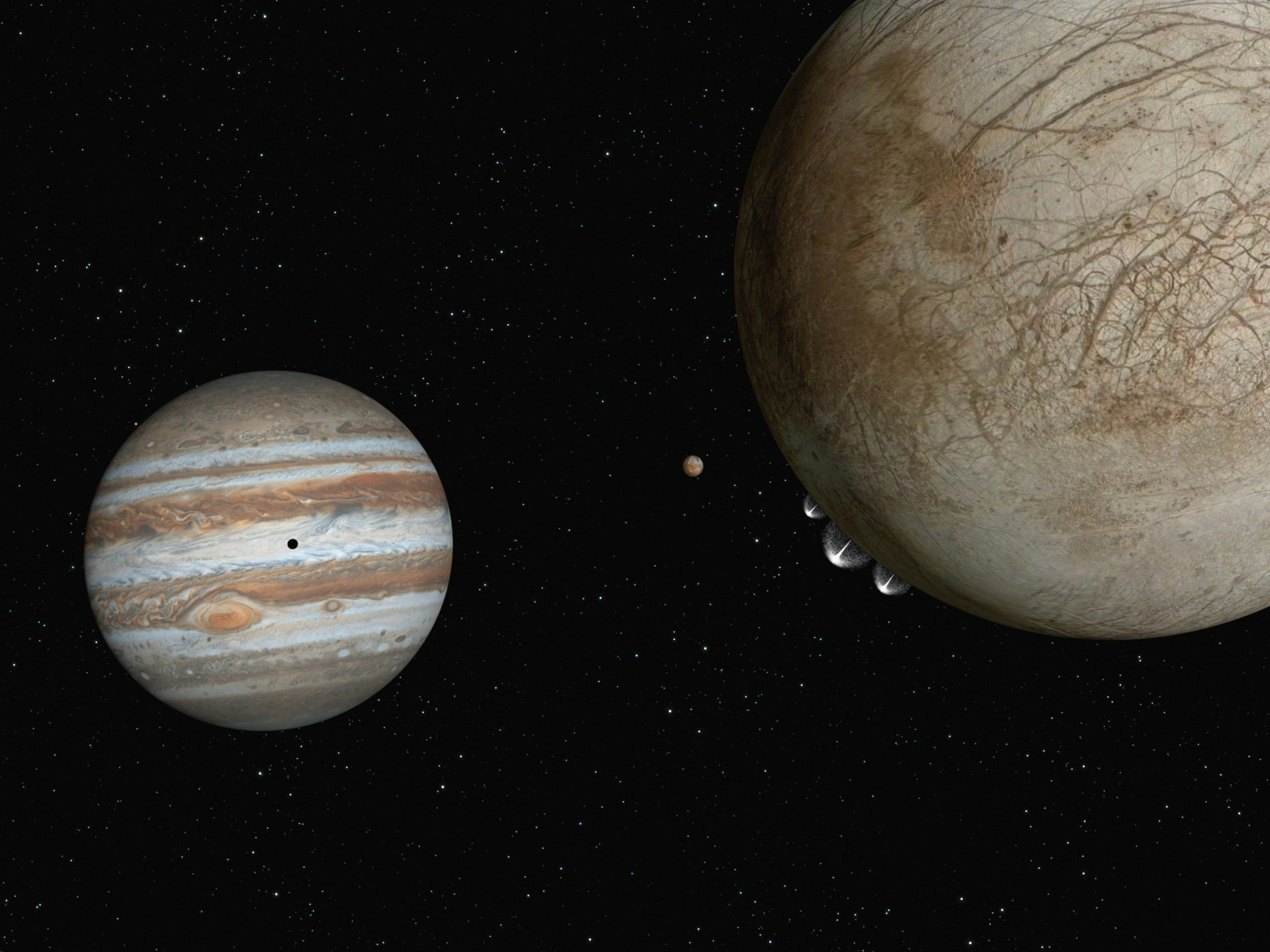

Will exploration of Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons, reveal secrets about extraterrestrial life? Photo credit: NASA Hubble Space Telescope via Unsplash

On 14 October, scientists and space enthusiasts from around the world held their breath as NASA’s Europa Clipper mission took flight from the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida. After having its launch delayed due to hurricane Milton, the spacecraft has finally set off on its 1.6-billion-mile journey across the solar system to arrive at Europa, one of Jupiter’s 95 moons. Upon its arrival at Europa in 2030, the craft will make 49 flybys of the moon, collecting data to help reveal if the icy ocean world has the right conditions to host extra-terrestrial life.

humanity first explored the giant planet and its moons in the early 1970s …

Europa—alongside Ganymede, Callisto, and Io—is one of Jupiter’s Galilean moons, named after the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who first observed them in 1610. The Jupiter system is no stranger to spacecrafts; humanity first explored the giant planet and its moons in the early 1970s when the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecrafts flew past them. In 1979, NASA returned with the Voyager 1 and 2 missions that were the first to send images of Jupiter back to Earth and have since continued past the edge of the solar system and into interstellar space. Voyager 1 is now the furthest spacecraft from Earth. Images and data sent back to Earth suggested that Europa might be an icy moon—with a subsurface ocean of liquid water beneath an icy outer shell. The Galileo mission was then sent to the Galilean moons in 1989, completing flybys of all four moons, including 12 flybys of Europa. Now, with more and more evidence of Europa’s icy ocean possessing the conditions necessary for sustaining life, Europa Clipper, NASA’s largest-ever planetary mission spacecraft, is the first dedicated mission to the moon. It joins the European Space Agency’s (ESA) JUICE mission that is already on its way to the Jupiter system, launched in April 2023. Together they will hopefully confirm the presence of a Europan subsurface salty ocean, determine the thickness of the icy shell, and investigate if Europa really does have the ingredients and conditions necessary to develop and sustain life.

Based on the life we see on Earth, scientists think that for life to evolve on a planetary body, three main requirements are needed: an energy source, the correct chemical components to form life, and temperatures allowing for liquid water. If the presence of a subsurface ocean on Europa and its composition can be confirmed, then all three requirements will be met on the moon. Tidal heating (where Europa is stretched due to interaction with Jupiter’s gravitational field) alongside chemical redox reactions in the water can provide energy sources for life to be sustained.

the lack of impact craters…suggest an icy surface…

Decades of spacecraft observations have suggested the presence of this subsurface ocean on Europa. Fractures imaged on its surface, and the lack of impact craters (which you would expect to see on any solar system body due to bombardment by meteorites) suggest an icy surface that is able to move around and settle independent of the subsurface, which would make sense if the subsurface was a liquid. The Galileo missions made key observations to show that Jupiter’s magnetic field was disrupted around Europa, suggesting the ocean must be able to conduct electricity, and therefore must be salty. Clipper now aims to make more observations looking at the tidal range of the moon’s surface along with its composition to confirm whether the subsurface ocean exists and in what form. If true, Europa will join several other ocean worlds in our solar system, such as two of Saturn’s moons—Titan and Enceladus.

To confirm the presence of the ocean, the spacecraft is carrying nine scientific instruments, the most advanced to ever enter the outer solar system. The spacecraft weighed about 6000kg at launch, almost half of that being fuel to power the 24 engines needed to complete its journey. Alongside the fuel, it has two large solar arrays that will spread out to be the length of a basketball court, allowing the robotic system to be run by solar power. Before heading off to the Jupiter system, Clipper will complete a flyby of Mars and then Earth; using the gravity of the two planets to essentially slingshot itself into the outer solar system. It will then spend about a year altering its trajectory and travelling to Europa for the first flyby in April 2030. Once it has reached Jupiter, Clipper will complete several flybys, imaging almost the entirety of Europa’s surface and collecting valuable data to help us learn more about the moon’s ocean (if it exists) and its interior.

As the Clipper scientists wait anxiously for the next six years for the spacecraft to arrive at its destination, we can only begin to imagine the decades of science and engineering that have gone into being able to send a spacecraft off to distant moons and to fathom what the data might reveal about the possibility of life beyond Earth.